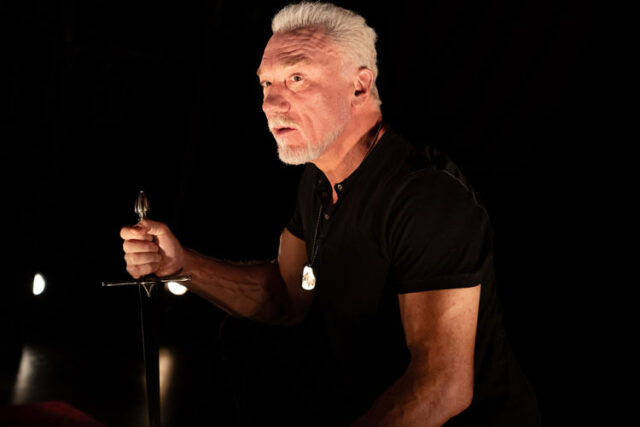

Raina (Shanel Bailey) asks her mother (Karen Ziemba) to be quiet about an uninvited guest (Kesha Moodliar) in Arms and the Man (photo by Carol Rosegg)

ARMS AND THE MAN

Theatre Row

410 West 42nd St. between Ninth & Tenth Aves.

Tuesday – Sunday through November 18, $71.50

gingoldgroup.org

www.theatrerow.org

It’s seldom a good sign when the actors onstage are having more fun than the audience. Such is the case with Gingold Theatrical Group’s (GTG) latest George Bernard Shaw adaptation, Arms and the Man. Continuing at Theatre Row through November 18, the production features several scene introductions with the cast at the front of the stage, delivering their lines right to the seats, preparing the audience for what comes next. Director David Staller notes in the script that Shaw was going to use this convention of actors speaking directly to the audience in a filmed version of the play but they made Major Barbara instead. Staller explains, “Thanks to [Shaw biographer] Sir Michael Holroyd, notes and letters from [veteran Shaw actor] Maurice Evans, and documents at the British Library, we have attempted to honor Shaw’s bold notion of employing the actors’ direct address and to view this world through a world of a Victorian toy theater.”

The evening begins with the cast of seven welcoming the audience to the show and introducing their roles. “Don’t worry; it’s Shaw but it’s short,” one says. “We’re determined to create a world of magic for you,” another promises. It’s a charming beginning that can’t maintain its appeal.

Lindsay Genevieve Fuori’s set is adorable, an elegantly outlined space, evoking a toy theater, that serves alternately as a bedroom, drawing room, and garden patio of a fancy abode in Bulgaria where the Petkoffs live in splendor: Major Paul Petkoff (Thomas Jay Ryan), his wife, Catherine (Karen Ziemba), and their daughter, Raina (Shanel Bailey). They are taken care of by their maid, Louka (Delphi Borich), who sees it all, and the ever-efficient major domo, Nicola (Evan Zes).

The 1885 Serbo-Bulgarian War is well underway, where Reina’s fiance, the brave blowhard Major Sergius Saranoff (Ben Davis), is leading the charge. Amid a barrage of gunfire below, a ragged enemy soldier, Captain Bluntschli (Kesha Moodliar), sneaks into Raina’s bedchamber, just looking for a reprieve from the battle. After hiding him from a Russian officer (Zes), Raina reevaluates her relationship with Sergius as everyone takes stock of what they want out of life.

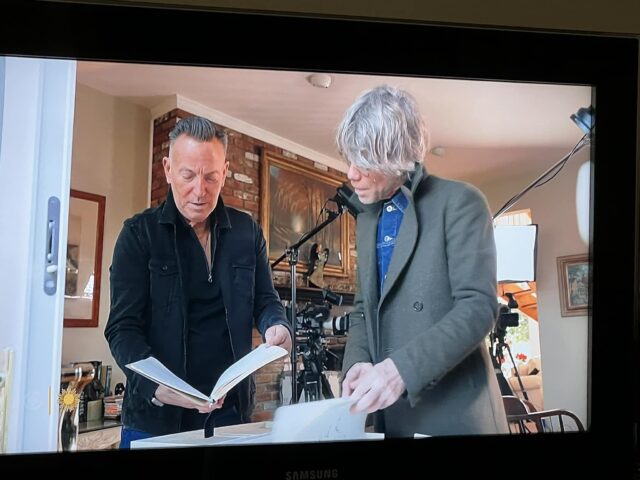

Major Paul Petkoff (Thomas Jay Ryan) and Major Sergius Saranoff (Ben Davis) share a laugh as Catherine (Karen Ziemba) and Raina (Shanel Bailey) look on sternly in Shaw adaptation (photo by Carol Rosegg)

The fourth of Shaw’s sixty-five plays, Arms and the Man debuted in 1894 on the West End and has been produced on Broadway seven times, most recently in 1985 at Circle in the Square with Kevin Kline, Glenne Headley, and Raul Julia, directed by John Malkovich. George Orwell famously raved, “It is probably the wittiest play [Shaw] ever wrote, the most flawless technically, and in spite of being a very light comedy, the most telling.” Alas, little of that is evident in Staller’s adaptation. The costumes (by Tracy Christensen) and the pacing were off; while we were told early on that there were to be three acts with two intermissions, that second interval never arrived, making me uncomfortable as I wriggled in my seat.

Shaw takes on class and war in this comedy of manners; we get plenty of class and war but unfortunately not much comedy in this rendition, which attempts to add contemporary relevancy. Scenes feel tenuously stitched together; characters are underplayed or overplayed, creating a mishmash of the narrative. The title comes from the opening words of Virgil’s Aeneid: “Arms and the man I sing, who, forced by fate / And haughty Juno’s unrelenting hate, / Expelled and exiled, left the Trojan shore,” an epic poem about war and power; that reference falls flat at Theatre Row.

GTG kicked off its Project Shaw in 2009, presenting just about everything Shaw ever wrote, from full-length and one-act plays to sketches. Their recent shows have been hit-or-miss, from the exquisite Mrs. Warren’s Profession to the less-charming Caesar & Cleopatra and Heartbreak House

At one point in Arms, Reina declares, “The world is really a glorious world for women who can see its glory and men who can act its romance! What happiness! What unspeakable fulfillment!”

If only more of that were evident in this wartime farce that lacks ammunition.

[Mark Rifkin is a Brooklyn-born, Manhattan-based writer and editor; you can follow him on Substack here.]