Karen Ziemba leads a lovely ensemble in revival of Mrs. Warren’s Profession

MRS. WARREN’S PROFESSION

Theatre Row

410 West 42nd St. between Ninth & Dyer Aves.

Through November 20, $73 (save $20 with code MWPGM)

gingoldgroup.org

bfany.org

Gingold Theatrical Group returns to live theater with a charming and delightful revival of Bernard Shaw’s Mrs. Warren’s Profession, continuing at Theatre Row through November 20. GTG artistic director David Staller adapted the script from several versions Shaw wrote as well as a proposed screenplay, resulting in a lighthearted, peppery satire of Victorian mores and societal prejudices that feels fresh and sprightly today.

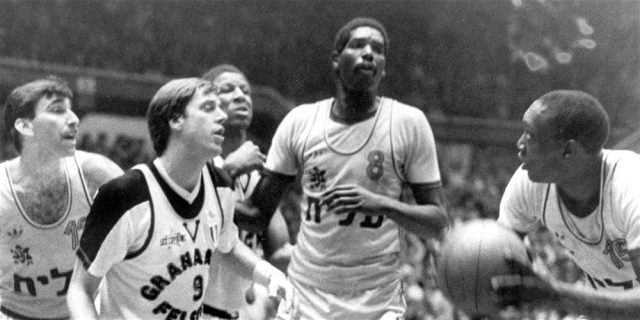

Inspired by Henrik Ibsen and his own 1882 novel, Cashel Byron’s Profession, about a man who hides his profession as a boxer from the woman he loves, Shaw’s play is set in 1912 in a country home in Surrey. Vivie (Nicole King), who has recently graduated from university with a degree in mathematics and is preparing to work in the city as an actuary, is waiting for her wealthy mother (Karen Ziemba) to arrive. Vivie has spent much of her life in boarding schools and doesn’t know her mother very well, and it soon becomes apparent that there’s no father in the picture. They are joined by three friends of Mrs. Warren’s: the pompous aristocrat Sir George Crofts (Robert Cuccioli), the architect Praed (Alvin Keith), Rev. Samuel Gardner (Raphael Nash Thompson), and the reverend’s son, Frank (David Lee Huynh).

Crofts, Praed, and the elder Gardner are aware of how Mrs. Warren made her money, first as a prostitute, then as a madam. It’s possible that one of them is Vivie’s father, but that is not exactly preventing them from wooing the young woman with talk of art, romance, faith, and financial success. Meanwhile, Frank, a gold-digging gambler who has known Vivie since childhood, is in love with her, or at least with her money, pitting the men against one another even though Vivie has made it clear that she is ready to make a life for herself in London, unattached.

Vivie (Nicole King) and Frank (David Lee Huynh) consider their futures in Mrs. Warren’s Profession

Handsomely directed by Staller, the comedy of manners and equality plays out over Brian Prather’s lovely white set, consisting of a few chairs, several long steps in the center that evoke the ups and downs of class, and tall, lacy white shelves containing books and dolls, with drapes and ivy nearly swallowing it all up, nature infringing on this community of calculating machinations. Asa Benally’s dainty period costumes and Brandy Hoang Collier’s props add to the overall gracefulness.

The play caused controversy when it debuted in London in 1902 (after having been banned since 1895) and in New York City three years later, primarily because of Mrs. Warren’s profession, even though it’s never mentioned by name. It was written as a call for women’s rights, which still feels relevant more than a century later, as sex workers fight for legalization and respect and women have had to leave the work force in droves during the pandemic to do unpaid labor at home.

In her off-Broadway debut, King is terrific as Vivie, a forward-thinking woman who insists she does not need a man in her life in order to succeed. The men surround her like hungry bees, but she is not about to let them suffocate her; her strong handshake alone intimidates them, revealing her power from the start. When Praed praises that her mother did not raise Vivie “conventionally,” she replies, “Oh! Have I been behaving unconventionally?” He answers, “Oh no: oh dear no. At least, not ‘conventionally unconventionally,’ you understand. . . . When I was your age, young men and women were afraid of each other.” Vivie appears afraid of nothing. “In today’s world there’d be no stopping her,” Shaw wrote. Vivie later tells her mother, “People are always blaming circumstances for what they are. I don’t believe in circumstances. The people who get on in this world are the people who get up and look for the circumstances they want, and, if they can’t find them, make them.”

And just as Vivie is not about to make any apologies for the choices she’s making and the circumstances she’s creating, Mrs. Warren, wonderfully portrayed by Tony winner Ziemba (Contact, Curtains), is proud of her own past, doing whatever she feels necessary to rise up from her lowly beginnings. (The potent role has previously been played by Joan Plowright, Dana Ivey, Elizabeth Ashley, Cherry Jones, and Lilli Palmer.) “What’s a woman worth? What’s life worth? Without self-respect!” she says to Vivie. “Why am I independent? Because I always knew how to respect myself and control myself.”

Shaw addressed gender stereotypes in his long and detailed 1902 “Author’s Apology,” which called to task critics and censors who, he believed, missed the salient points of the play, including celebrating the title character. “The notion that Mrs. Warren must be a fiend is only an example of the violence and passion which the slightest reference to sex arouses in undisciplined minds, and which makes it seem natural for our lawgivers to punish silly and negligible indecencies with a ferocity unknown in dealing with, for example, ruinous financial swindling. Had my play been titled Mr. Warren’s Profession, and Mr. Warren been a bookmaker, nobody would have expected me to make him a villain as well.”

In the hands of King and Ziemba, and Shaw and Staller, Vivie and Mrs. Warren, each heroic in her own way, tower over the men, who are mere flies buzzing about. Shaw has nothing to apologize for.