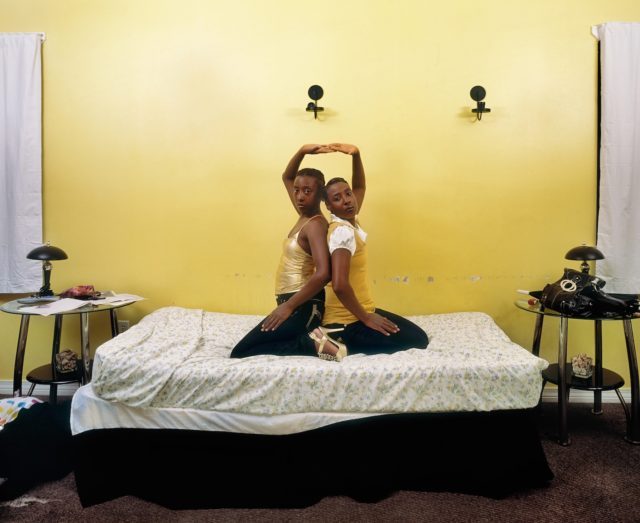

Into the Woods features a dazzling all-star cast with superstar understudies (photo by Matthew Murphy and Evan Zimmerman)

INTO THE WOODS

St. James Theatre

246 West Forty-Fourth St.

Tuesday – Sunday through January 8, $69-$159

intothewoodsbway.com

At intermission of the spectacular revival of Into the Woods, I was heading outside for a breath of fresh air when I saw a notice posted on the doors that the show was not yet over, that there was a second act. At first I wondered who would leave the theater at this point, but then I thought about how nearly perfect the first act was, how everything seemed to be wrapped up in a neat little package, with everybody onstage and in the audience elated and satisfied.

But in James Lapine and Stephen Sondheim’s devilishly clever show, “happily ever after” is a misnomer, more of a warning than a coda. As the Narrator (David Patrick Kelly) had ominously just informed us, “To. Be. Continued.” Everyone’s jubilation is about to come tumbling down, like a giant falling from the sky — although one can find plenty of exhilaration in the dark side as well.

Inspired by Bruno Bettelheim’s 1976 Freudian book The Uses of Enchantment: The Meaning and Importance of Fairy Tales, Lapine and Sondheim’s musical debuted at San Diego’s Old Globe in 1986 and moved to Broadway the following year, earning ten Tony nominations and winning three, losing the Best Musical award to The Phantom of the Opera. This new version, which premiered at New York City Center’s “Encores!” series in May, has made a super-smooth transition to the St. James, maintaining its brilliant streamlined adaptation.

The nearly-three-hour show, which has been extended through October 16, is a mashup of fairytale favorites with some added central characters. The stage is dominated by a fifteen-piece orchestra conducted by Rob Berman, who leads the musicians through Sondheim’s complicated, unpredictable score. The actors spend most of the show on a narrow, horizontal section at the front of the stage, with minimal props, highlighted by miniature versions of their forest homes dangling from the ceiling, teasingly just out of reach. In addition, they occasionally wander through the orchestra, running around and hiding behind white birch trees that have come down from above.

The story is built around three wishes. Cinderella (Phillipa Soo) is suffering through a miserable existence, terrorized by her stepmother (Nancy Opel) and stepsisters, Florinda (Brooke Ishibashi) and Lucinda (Ta’Nika Gibson), while her father (Albert Guerzon) offers her no support. “I wish to go to the festival — and the ball . . . more than anything,” Cinderella sings, referring to a grand party being thrown by the handsome prince (Gavin Creel).

Jack (Cole Thompson, although I saw Alex Joseph Grayson) and his mother (Aymee Garcia) are worried that they might lose their farm, so the mother sends Jack off to sell his beloved old and ragged cow, Milky White (Kennedy Kanagawa). “I wish my cow would give us some milk, more than anything,” Jack croons.

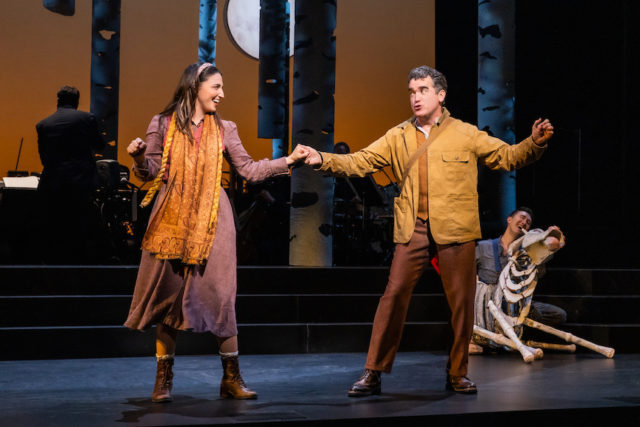

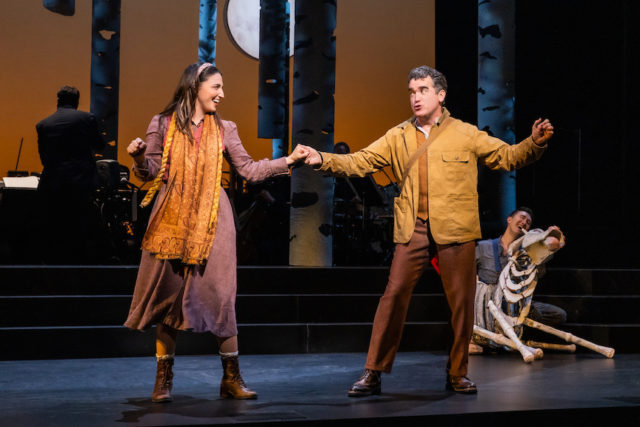

And the Baker (Brian D’Arcy James; I saw Jason Forbach) and his wife (Sara Bareilles) are desperate to have a baby. “I wish . . . more than the moon . . . more than life . . . I wish we might have a child,” the couple, invented for the show, opine.

Milky White (Kennedy Kanagawa) sits in the back as the Baker (Brian D’Arcy James) and his wife (Sara Bareilles) come up with a plan (photo by Matthew Murphy and Evan Zimmerman)

Other familiar and new characters also show up in the threatening forest. Little Red Ridinghood (Julia Lester; I saw Delphi Borich) stops at the bakery to bring some treats to her granny (Annie Golden) but better be aware of the hungry Wolf (Creel). “Into the woods / to bring some bread / to Granny who / is sick in bed. / Never can tell / what lies ahead. / For all I know, she’s already dead,” Red declares. Rapunzel (Alysia Velez) has been locked up in a tower, where another handsome prince (Joshua Henry) seeks to rescue her. A Mysterious Man (Kelly) pops up from time to time, telling riddles and positing, “When first I appear, I seem delirious. But when explained, I am nothing serious.”

Everything is set in motion by the Witch (Patina Miller), who lives next door to the Baker and his wife. She had cursed the Baker’s family — which includes the sister he never knew he had, named Rapunzel — deeming it impossible for them to have children, but she now offers to reverse it in exchange for “the cow as white as milk,” “the cape as red as blood,” “the hair as yellow as corn,” and “the slipper as pure as gold.” She promises, “Bring me these / before the chime / of midnight / in three days’ time, / and you shall have, / I guarantee, / a child as perfect / as child can be. / Go to the wood!”

And off they go, into the woods, where they have to determine how far to compromise their morals in order to acquire the four elements that will allow them to finally have a baby. These decisions ring true with audience members, who, in our own lives, regularly face ethical decisions. “Into the woods / without regret, / the choice is made, / the task is set,” the Baker, his wife, Cinderella, Jack, and Jack’s mother sing in unison. “Into the woods / to get my (our) wish, / I don’t care how, / the time is now.”

But when a widowed Giant (voiced by Golden) comes down from her haven in the sky to avenge her husband’s death, everyone’s future is destined to not be so happy after all.

In the last ten years, I’ve seen two previous adaptations of Into the Woods, from the Public Theater at the Delacorte in 2012 and Fiasco Theater for Roundabout at the Laura Pels in 2015. Both were lovely, memorable productions that were very different from each other but thoroughly satisfying in their unique approaches to a beloved musical.

First-time Broadway director Lear deBessonet (Pump Boys and Dinettes, transFigures), the head of Encores! and the founder of Public Works, and choreographer Lorin Latarro (Fiasco’s Merrily We Roll Along, Assassins for Encores!), expertly guide the actors across the stage, up and down the handful of steps, and through the trees, making the most of the tight quarters; the charming scenic design is by David Rockwell, with lighting by Tyler Micoleau, sound by Scott Lehrer and Alex Neumann, and lovely music direction by Rob Berman. The tasty costumes are by Andrea Hood, with hair, wig, and makeup design by the extraordinary Cookie Jordan.

The Wolf (Gavin Creel) has an evil plan in store for Little Red Ridinghood (Julia Lester) (photo by Matthew Murphy and Evan Zimmerman)

The cast is a true ensemble; several friends and colleagues saw different actors in key roles than I did, and everyone raved about them all, whether the understudy or the award-winning star. But two performers do stand out.

Miller brings down the house when she belts out “Last Midnight,” driving the crowd into a frenzy as she cries out, “It’s the last midnight, / it’s the last verse. / Now, before it’s past midnight, / I’m leaving you my last curse: / I’m leaving you alone.” Miller won a Tony as Leading Player in Diane Paulus’s 2013 Broadway revival of Pippin, but I missed her when I went; I instead saw the wonderful Stephanie Pope, who has had quite a career of her own.

But Kanagawa nearly steals the show as Milky White. Puppet designer James Ortiz (2022 Drama Desk Award winner for Best Puppet Design for The Skin of Our Teeth) has created a tender and fragile cow out of cardboard — part Slinky, part accordion — operated by Kanagawa, who had never worked with puppets before. He masterfully moves Milky White as the cow’s destiny is threatened, making sure we feel every emotion in her static foam eyes, from joy to sadness, as if it were a living creature in front of us. It’s a bravura performance that is receiving Tony buzz.

“If we hope to live not just from moment to moment, but in true consciousness of our existence, then our greatest need and most difficult achievement is to find meaning in our lives,” Bettelheim writes in the introduction of The Uses of Enchantment. “Our positive feelings give us the strength to develop our rationality; only hope for the future can sustain us in the adversities we unavoidably encounter.”

This latest adaptation of Into the Woods zeroes in on how Lapine’s book and Sondheim’s music and lyrics form a fairy tale for both kids and adults, about human beings’ instinctual desires, alongside their darkest fears. And don’t worry about the second act; it turns out that happily ever after is always within reach.