Real-life father and son Reed Birney and Ephraim Birney star in Chester Bailey at the Irish Rep (photo by Carol Rosegg)

CHESTER BAILEY

Irish Repertory Theatre, Francis J. Greenburger Mainstage

132 West 22nd St. between Sixth & Seventh Aves.

Wednesday – Sunday through November 20, $50-$70

212-727-2737

irishrep.org

Chester Bailey is one of the best plays of the year, a pristine example of the beauty and power of live drama.

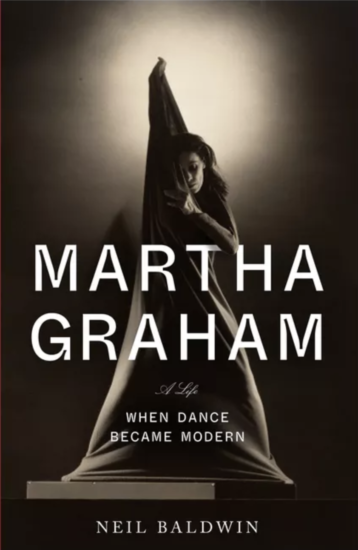

In January 2015, the Irish Rep presented a free staged reading of Emmy-nominated writer and producer Joseph Dougherty’s Chester Bailey at the DR2 Theatre, directed by Emmy and Tony nominee Ron Lagomarsino and featuring Tony nominee Reed Birney as a doctor caring for a young man (Noah Robbins) who has suffered extreme, unspeakable trauma.

The show has been transformed into a touching, gorgeous, must-see production, running at the Irish Rep through November 20. Birney stars as Dr. Philip Cotton, a specialist working with soldiers, including amputees, suffering from battle fatigue and “other injuries that might keep a man from getting back to the life he had as a civilian.” It’s 1945, near the end of WWII, and Dr. Cotton has accepted a position at a Long Island hospital named after Walt Whitman, the poet who served as a nurse during the Civil War.

“The families of the men I was treating wanted their sons and husbands to be the way they were before the Solomons and the Philippines,” Dr. Cotton tells us. “I tried. Tried to take that look out of their eyes. That look acquired in the jungle. My successes were ‘limited.’”

Dr. Cotton’s newest case is Chester Bailey — played by Birney’s son, Ephraim Birney — a man in his midtwenties who refuses to acknowledge that he has lost both eyes and hands in a horrific incident at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, where he worked along the keel of a mine sweeper. Dr. Cotton might technically be unable to take that look out of Chester’s eyes, but the character is played with eyes and hands that are filled with emotion. Chester is overwhelmed with guilt because his parents got him the job in order to keep him out of the war; he had wanted to enlist, like most of the men he knew were doing, but his mother was determined to protect him.

Chester Bailey (Ephraim Birney) creates his own reality out of trauma in superb New York premiere (photo by Carol Rosegg)

“One night, I was reading the paper in the kitchen with the radio on, listening to the war news, and my folks came in and my mother was smiling,” he explains directly to the audience. “She said, ‘We’ve got a late Christmas present for you, Chester. Your father got you a job at the Navy Yards. Isn’t that wonderful?’ When she said job, she meant reserved occupation. She meant I wouldn’t be drafted because I’d be doing war work. Doing my patriotic part, but coming home to Vinegar Hill at the end of my shift. . . . My father looked up at me and I could see in his eyes this was just how it was going to be and there was nothing either one of us could do about it.” The horrible irony was that Chester ended up with the type of injuries men get on the field of battle anyway.

Chester has created a fantasy world in which he can still see and touch things. He describes in detail a copy of van Gogh’s Langlois Bridge at Arles that he thinks is hanging in his room. The 1888 painting relates to Chester’s state of mind: It depicts a woman in black standing on a small drawbridge under blue skies, holding a black umbrella as if in a dark storm. In the actual historical war, the bridge was blown up by the Germans in 1944, so it wouldn’t have existed in 1945 when Chester was supposedly seeing the print of it, made by an artist who would shortly thereafter cut off his own ear and live in an asylum. In fact, Chester believes that the only lasting effect the incident had on him was that he lost one ear. Meanwhile, we learn that Dr. Cotton is color blind, so he cannot process critical aspects of the painting that Chester believes is on the wall.

The first part of the play primarily goes back and forth between Chester and Dr. Cotton talking to the audience, delivering monologues about themselves. Chester discusses his parents and recalls going dancing with a former girlfriend at Luna Park, heading into Manhattan by himself for what he hoped would be a night of revelry, and falling instantly in love with a young red-haired woman selling papers at a newsstand in Penn Station.

Dr. Cotton carefully watches Chester sharing these memories, as if he’s not in the room with him, then adds elements from his own personal and professional life that intersect with similar themes that Chester’s deals with, just from a different angle; the doctor discusses his daughter, Ruthie; his wife’s infidelity and their eventual divorce; his career choices; going to the country club; his flirtation with his boss’s wife; and waiting at Penn Station to get home to Turtle Bay after work.

“It was difficult for Chester’s father to visit him on Long Island,” Dr. Cotton says. “He’d come on weekends, get off the train at the same station I used before I moved, walk the mile and a half around Holy Rood Cemetery to the hospital on Old Country Road. I think of him standing on the platform I used. Each of us waiting for the light of the westbound. Waiting. Not thinking. Trying not to think.”

In the second half, doctor and patient interact, as Dr. Cotton is determined to make Chester face what has happened to him and Chester keeps insisting he has eyes that can see and hands that can touch. Revisiting the incident, Chester tells his incorrect version. “Remember anything else?” Dr. Cotton says. “Nothing real,” Chester responds. “Do you remember anything that isn’t real?” the doctor asks before exploring Chester’s dreams and hallucinations.

The Irish Rep is justly celebrated for its sets, and Chester Bailey is no exception. Two-time Tony winner John Lee Beatty’s (Sweat, Junk) stage design combines a hospital room with bed, wheelchair, and table with the grandeur of old Penn Station, with stanchions in concrete blocks and a curved metal ceiling seemingly made out of railroad tracks. Brian MacDevitt’s lighting includes dangling lightbulbs that glow like stars in the night sky, going on forever in the mirrored walls. “The concourse of Penn Station is like the hull of a ship turned upside down, like you were looking up at the keel,” Chester says. “But instead of being all dark like where I work, it’s light. The light is just in the air. And there are no shadows. You want to know what the light looks like in heaven? You go to the main concourse of the Pennsylvania Station.” Beatty and MacDevitt have captured that image beautifully.

One of New York’s finest, most consistent actors, Reed Birney (The Humans, Man from Nebraska) inhabits the role from the very start, portraying Cotton not as a heroic wartime doctor but as a man with his own shortcomings. Whether he wants to or not, he becomes a kind of father figure to Chester, made all the more palpable since Ephraim (Exploits of Daddy B, Leon’s Fantasy Cut), who was cast first, is his son. While Reed moves slowly and carefully, Ephraim is much more active, jumping around with an eagerness that counters his character’s inability to come to terms with what has happened to him.

Two-time Drama Desk–nominated director Ron Lagomarsino (Digby, Driving Miss Daisy) guides the ninety-minute show with a graceful elegance; there’s nary a stray note in the play, which is not just about the travails of a single man but about family and everyday existence, about the big and small moments. The relationship between parents and their children are echoed here by a doctor and patient who happen to be father and son. At one point, Chester asks Dr. Cotton why he didn’t go into his father’s printing and binding company. “How come it wasn’t Cotton and Son?” he wonders. Dr. Cotton answers, “He wanted me to go to college. I wanted to be a doctor.” It takes on extra meaning in that Ephraim has followed his father and mother, actress Constance Shulman, into the family business. (All three appeared in the offbeat 2022 film Strawberry Mansion.)

Early on, Dr. Cotton states, “If there’s one thing reality can’t tolerate, it’s competition.” It’s a great line in a great play that brilliantly explores the human condition and the realities that each of us creates to help us deal with whatever life throws our way.