Wade Guyton’s reflective “U” sculptures are a highlight of midcareer survey at the Whitney (photograph by Ron Amstutz)

Whitney Museum of American Art

945 Madison Ave. at 75th St.

Wade Guyton OS through January 13

Richard Artschwager! through February 3

212-570-3600

www.whitney.org

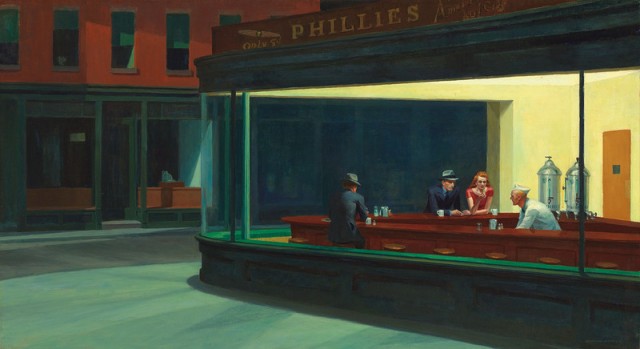

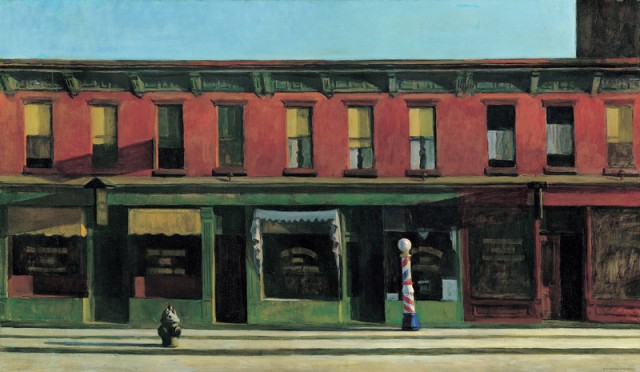

The Whitney is currently home to a pair of splendid exhibitions by two New York City-based artists that relate surprising well to each other despite being, at initial glance, so very different. “Wade Guyton OS” is the first midcareer survey of forty-year-old Indiana native Wade Guyton, who worked with curator Scott Rothkopf to turn the third floor of the Whitney into a kind of three-dimensional personalized computer operating system, featuring more than eighty works, including new site-specific pieces created for the show. The bulk of Guyton’s oeuvre consists of paintings he first develops in Microsoft Word, then prints out on linen using a medium-size Epson UltraChrome inkjet printer. Much is left to chance, as he folds the large-scale linen pieces to fit into the printer, but the material gets caught in the machine, resulting in random rips, tears, streaks, and splotches. He often incorporates letters in his works, including a series of 2006 pieces in which multiple versions of the letter U hover in or over a raging fire, and a 2007 black-and-white series of mangled Xs. He has also used the letter U in a dazzling collection of U-shaped mirrored stainless-steel sculptures containing reflections of one another as well as of the Whitney’s ceiling and floor and the works hanging on the wall nearby, playing with reality and perception, what is real and what is not. Guyton overprints onto pages from books, referencing art history while displaying them in linoleum-lined vitrines meant to evoke the linoleum floor in the kitchen of his studio. In addition, Guyton often uses found objects in his work. “Untitled Action Sculpture (Five Enron Chairs)” comprises five side-by-side Marcel Breuer Cesca chairs that Guyton acquired on eBay. “Untitled Action Sculpture (Chair)” was fashioned from a broken tubular steel Cesca chair he found on the street in the East Village and twisted into a new form. The chairs take on added meaning since Breuer is the architect who designed the Whitney building, which the institution will soon be leaving to head to new digs downtown.

Richard Artschwager, “Exclamation Point (Chartreuse),” plastic bristles on a mahogany core painted with latex, 2008 (© Richard Artschwager / photo by Robert McKeever)

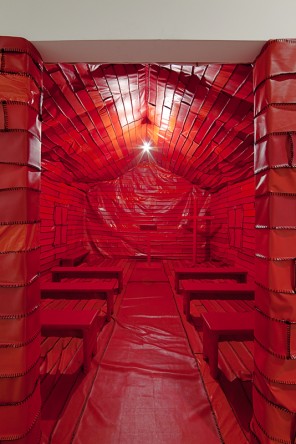

Born in Washington, DC, Artschwager was forty-two when he had his first solo exhibition, at Leo Castelli in 1965, seven years before Guyton was born. Now eighty-nine, Artschwager continues to amass a hard-to-categorize collection of painting, drawing, sculpture, and installation renowned for its use of offbeat materials. His gray paintings on Celotex have a texture that gives them a mysterious sculptural quality. Paintings such as “Plaque” and sculptures such as “Hair Sculpture — Shallow Recess Box” contain rubberized horsehair. And such pieces as “Door II” and “Bookcase III” are made of that classic suburban element, Formica. Guyton’s chairs might actually feel at home at several of Artschwager’s tables, including 1964’s “Description of Table,” composed of melamine laminate on plywood, and 1988’s “Double Dinner,” made of wood, Formica, paint, and rubberized hair that makes it look like it’s alive. In the 1970s, Artschwager concentrated particularly on household objects, compiling nearly one hundred paintings and sculptures of a door, a window, a table, a basket, a mirror, and a rug. Whereas Guyton uses pages from books and magazines in his work, Artschwager has created such pieces as “Bookends,” “Untitled (Book),” and the aforementioned “Bookcase III,” none of which reveals actual pages or covers. And while Guyton uses the letters X and U, Artschwager has fun with quotation marks and, most vibrantly, exclamation points, one of which is composed of plastic chartreuse bristles and dazzles the mind. (Of course, another exclamation point makes its way into the exhibition’s name.) Artschwager also leaves his mark with a series of “blps,” elongated black dots that can be found at various places in the Whitney as well as on and around the High Line, near the Whitney’s future home. While “Wade Guyton OS” and “Richard Artschwager!” are not meant to be a dual exhibition, seeing them together offers fascinating insight into the work of two major artists, several generations apart, who view the world in unique, and at times startlingly similar, ways.