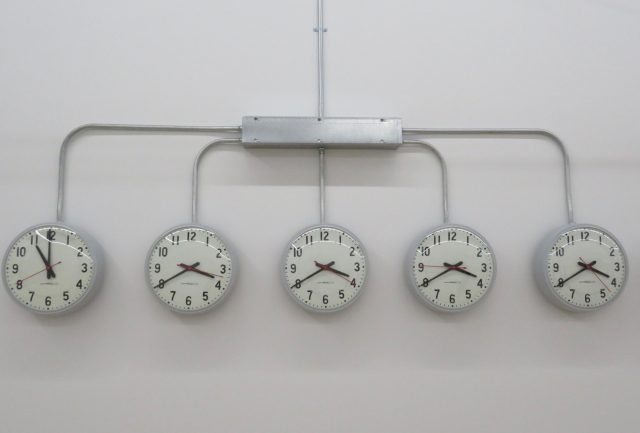

Jason Moran performs in Stan Douglas’s six-hour 2013 video Luanda-Kinshasa (© Stan Douglas / courtesy the artist and David Zwirner, New York)

Whitney Museum of American Art

99 Gansevoort St.

Through January 5 (adults $25, eighteen and under free

whitney.org

Atop his official website, Jason Moran identifies himself simply as “Musician.” As his retrospective at the Whitney reveals, he is much more than that. Born in Houston in January 1975, jazz pianist and composer Moran released his debut album, Soundtrack to Human Motion, twenty years ago and has expanded his horizons significantly since then. In addition to recording such discs as Facing Left, Same Mother, Artist in Residence, Bangs, and Looks of a Lot, many with his group, the Bandwagon, consisting of bassist Tarus Mateen and drummer Nasheet Waits, he collaborates with a bevy of visual artists, creates large-scale installations, and makes eye-catching drawings.

Jason Moran’s music-inspired drawings are a highlight of multidisciplinary show at the Whitney (photograph by Ron Amstutz)

The show, simply titled “Jason Moran,” is an eye-opening exploration of a multitalented artist, one of the most surprisingly delightful exhibits of the year. Upon entering the eighth floor, you encounter Moran’s “Run,” an ongoing series of works in which Moran tapes a sheet of paper, often a vintage player piano roll, over his piano, caps his fingers in charcoal and dry pigment of different colors, and plays the keyboard, resulting in horizontal abstract images that he gives such titles as Black and Blue Gravity and Two Wings 2. Screening on a loop in the far corner is Glenn Ligon’s The Death of Tom, what was supposed to be a re-creation of the final scene from Edison/Porter’s 1903 silent movie Uncle Tom’s Cabin, in which white actors played the main characters in blackface, but it turned into something very different because Ligon improperly loaded the film, resulting in what he called “blurry, fluttery, burnt-out black-and-white images, all light and shadows.” Moran improvised the score based on Bert Williams and Alex Rogers’s 1905 song “Nobody,” a hit for the black vaudeville team of Williams and George Walker, who fought racism on the road and stereotypes in their live performances. The Death of Tom might not have been the film Ligon set out to make, but it still takes on the same ideas.

Jason Moran exhibition features room of large-scale installations and three-channel videos (photograph by Ron Amstutz)

The main room of the exhibit is a beaut, featuring a trio of sculptural installations inspired by the stages of historic New York City jazz clubs, Harlem’s Savoy Ballroom, Midtown’s Three Deuces, and the Lower East Side’s Slugs’ Saloon. Three large screens show behind-the-scenes footage and/or full short films from ten of Moran’s collaborations, with such artists as Joan Jonas, Carrie Mae Weems, Adam Pendleton, Julie Mehretu, Ryan Trecartin, Lizzie Fitch, and Theaster Gates. In Lorna Simpson’s three-channel Chess, on two screens the artist plays chess in a mirrored room that makes it look like there are five of her; she’s dressed as a man in one, a woman in the other. Meanwhile, on the third screen, Moran plays the piano in a similarly mirrored space, improvising one of Brahms’s fifty-one exercises for piano. The black-and-white keyboard mimics the black-and-white chess sets as both Moran and Simpson display expert finger control.

Lorna Simpson, still from Chess, three-channel video, black-and-white, sound, 2013 (courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth / © Lorna Simpson)

Kara Walker’s National Archives Microfilm M999 Roll 34: Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen and Abandoned Lands: Six Miles from Springfield on the Franklin Road is a thirteen-plus-minute full-color video using her trademark cut-paper silhouettes like shadow puppets to tell the story of brutal violence perpetrated against an African American family during the Reconstruction era. (On October 12, Moran and Walker teamed up for the New York premiere of her Katastwóf Karavan, in which he played a steam-powered calliope housed in Walker’s old-fashioned circus wagon adorned with cut-steel silhouettes depicting powerful slave scenes.) In between some of the videos are interludes in which improvisations by Moran emit from a player piano on the “Three Deuces” stage. On January 3 and 4, Tiger Trio, consisting of pianist Myra Melford, bassist Joëlle Léandre, and flutist Nicole Mitchell, will perform at the Whitney as part of the “Jazz on a High Floor in the Afternoon” program.

Finally, around a corner, Stan Douglas’s Luanda-Kinshasa brings together Jason Moran and a group of other musicians in a fictitious recording session in a reconstruction of Columbia’s 30th Street Studio, known as the Church, where between 1949 and 1981 such artists as Bob Dylan, Aretha Franklin, Vladimir Horowitz, Billie Holiday, Charles Mingus, and Miles Davis made albums. Inspired by Jean-Luc Godard’s Rolling Stones concert film Sympathy for the Devil, Douglas films the band over two days in a 1970s-style setting, improvising as if this is a follow-up to Miles Davis’s 1971 album Live-Evil, part of which was recorded at the Church. Douglas himself improvises through the editing process, ending up with a six-hour jam session. Be sure to allow plenty of time to experience “Jason Moran,” an artistic jam session you won’t soon forget.