Cate Blanchett plays multiple characters in Julian Rosefeldt’s MANIFESTO

Park Ave. Armory, Wade Thompson Drill Hall

643 Park Ave. at 67th St.

Daily through January 8, $20

212-933-5812

www.armoryonpark.org

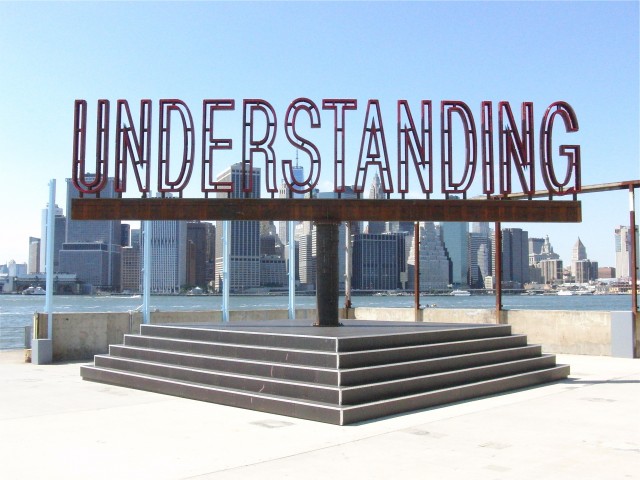

As visitors go from screen to screen in Julian Rosefeldt’s thirteen-channel installation, Manifesto, at the Park Ave. Armory, they’re bombarded with declarations from cultural missives by artists and philosophers dating back more than 150 years. Various words and phrases stick out, hanging in the air like bees buzzing around flowers: “originality,” “conflict,” “infinite and shapeless variation,” “decay,” “revolution,” “recklessness,” “absolute reality,” “glorious isolation,” “obsession,” freedom,” “everlasting change,” “the unconsciousness of humanity.”

I am against action; I am for continuous contradiction: for affirmation, too. I am neither for nor against and I do not explain because I hate common sense. I am writing a manifesto because I have nothing to say.

Art requires truth, not sincerity.

Logic is a complication. Logic is always wrong.

The words are all spoken by Oscar-winning actress Cate Blanchett (Notes on a Scandal, Blue Jasmine), who plays thirteen characters in twelve of the films, which each runs ten and a half minutes and are looped concurrently. She does not appear in the shorter prologue but does provide the narration. Among the characters she portrays are a homeless man, a grade school teacher, a factory worker, a punk rocker, a scientist, a news anchor, a choreographer, and a puppeteer.

Our art is the art of a revolutionary period, simultaneously the reaction of a world going under and the herald of a new era.

Originality is nonexistent.

Purge the world of intellectual, professional, and commercialized culture!

Rosefeldt (Trilogy of Failure, Deep Gold, The Ship of Fools), a photographer and filmmaker who was born in Munich and lives and works in Berlin, has an MA in architecture, so location plays a key role in the films, many of which take place in spectacular surroundings, interiors and exteriors, that would make Andreas Gursky drool, including an abandoned Olympic village, the Klingenberg CHP Plant, the Palasseum housing project, a former fertilizer factory, the ZDF Hauptstadtstudio, and the Humboldt Universität Department of Engineering Acoustics (in which a 2001-like monolith floats in the air). Each film begins and ends with Christoph Krauss’s camera lingering on the often jaw-dropping visuals.

We must create. That’s the sign of our times.

Fluxus is a pain in art’s ass.

Existence is elsewhere.

A homeless man screams out his thoughts on art in Julian Rosefeldt’s MANIFESTO (© 2015 Julian Rosefeldt and VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn)

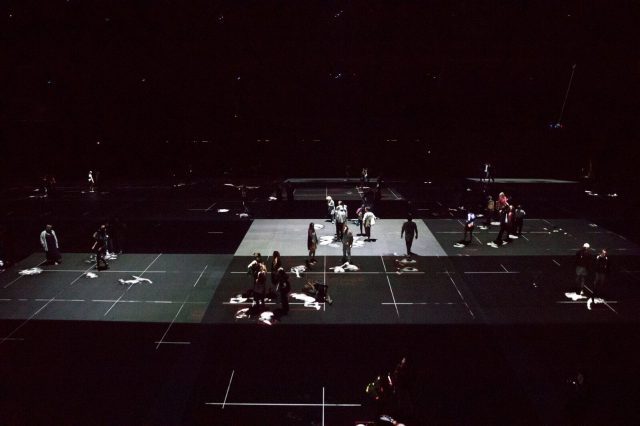

The statements are delivered in unique and inventive ways, with Blanchett, looking vastly different in each scene courtesy of Bina Daigeler’s costumes, Morag Ross’s makeup, and Massimo Gattabrusi’s hairstyling, playing a mourner giving a eulogy, a mother saying grace, a teacher presenting a lesson, a choreographer yelling at her troupe, a financial analyst spouting data, a crane operator incinerating garbage, and a CEO offering a new concept at a private board meeting in a seaside villa.

I am for art that is put on and taken off, like pants; which develops holes, like socks; which is eaten, like a piece of pie, or abandoned with great contempt, like a piece of shit.

No to the heroic. No to the anti-heroic.

Temporal and geographical alienation are forbidden.

Each section is dedicated to a separate artistic theory, discussing Pop Art, Conceptual Art / Minimalism, Fluxus, Surrealism / Spatialism, Dadaism, Suprematism / Constructivism, Stridentism / Creationism, Abstract Expressionism, Architecture, Futurism, Situationism, and Film. Heard today in this context, the statements range from the very funny to the extremely dry and boring, from the downright elitist to the realistic and relevant, from the sublime to the ridiculous.

Farewell to absurd choices.

Nothing is original.

In this period of change, the role of the artist can only be that of the revolutionary: it is his duty to destroy the last remnants of an empty, irksome aesthetic, arousing the creative instincts still slumbering unconscious in the human mind.

Close-ups of Cate Blanchett appear simultaneously in thirteen-screen installation at Park Ave. Armory (photo by James Ewing)

The quotations come from a wide variety of sources, from little-known essays to major influential texts. They include Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels’s Manifesto of the Communist Party, Kazimir Malevich’s Suprematist Manifesto, Dziga Vertov’s WE: Variant of a Manifesto, André Breton’s Manifesto of Surrealism, Lucio Fontana’s White Manifesto, Stan Brakhage’s Metaphors on Vision, Elaine Sturtevant’s Man Is Double Man Is Copy Man Is Clone, Lars von Trier and Thomas Vinterberg’s Dogma 95, and Claes Oldenburg’s I am for an art . . . , in addition to writings by Francis Picabia, Barnett Newman, Yvonne Rainer, Kurt Schwitters, Tristan Tzara, Sol LeWitt, Paul Eluard, Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc, Guillaume Apollinaire, and Werner Herzog.

The past we are leaving behind us as carrion. The future we leave to the fortune-tellers. We take the present day.

All of man is fake. All of man is false.

I believe in the pure joy of the man who sets off from whatever point he chooses, along any other path save a reasonable one, and arrives wherever he can.

About two-thirds of the way through each film, all of the characters portrayed by Blanchett, seen in extreme close-up, suddenly speak their lines in monotone unison, a kind of choral cacophony of chanting and singing that echoes throughout the massive Wade Thompson Drill Hall, an exhilarating moment that makes up for some of the pompous diatribe and intellectual masturbation that preceded it. It also is a grand statement for the critical importance of art, especially during tough times when countries face cultural and sociopolitical battles that threaten personal freedoms and liberties. But the best reason to experience Manifesto, which continues through January 8, is to watch a remarkable actress in a marvelous and memorable tour de force; Blanchett fans will also want to catch her in Anton Chekhov’s The Present, which is running on Broadway through March 19.