Park Ave. Armory’s Wade Thompson Drill Hall is transformed into a WWI military hospital in Doppelganger (photo by Monika Rittershaus / courtesy of Park Avenue Armory)

DOPPELGANGER

Park Avenue Armory, Wade Thompson Drill Hall

643 Park Ave. at 67th St.

September 22-28, $54-$259

212-933-5812

www.armoryonpark.org

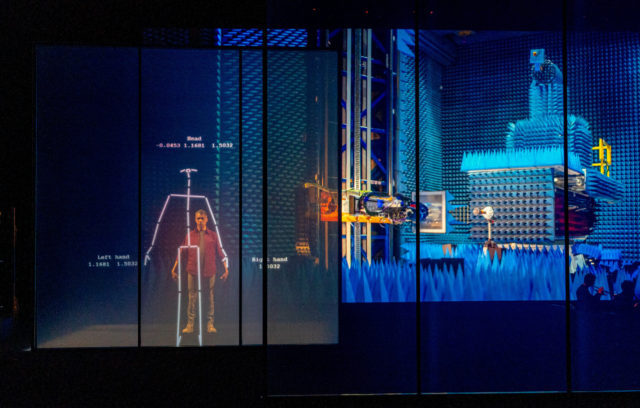

Park Avenue Armory once again confirms that its Wade Thompson Drill Hall is the most sensational performance space in New York City with the world premiere of Claus Guth’s bold and breathtaking Doppelganger.

In 1828, ailing Austrian composer Franz Schubert wrote “13 Lieder nach Gedichten von Rellstab und Heine,” a baker’s dozen of songs set to text by German poet, pianist, and music critic Ludwig Rellstab (originally written for Beethoven) and German poet and literary critic Heinrich Heine. Schubert died of syphilis in November of that year at the age of thirty-one; the works were published in 1829 as a fourteen-song cycle, Schwanengesang (“Swan Song”), with the addition of a song with lyrics by Austrian archaeologist and poet Johann Gabriel Seidl.

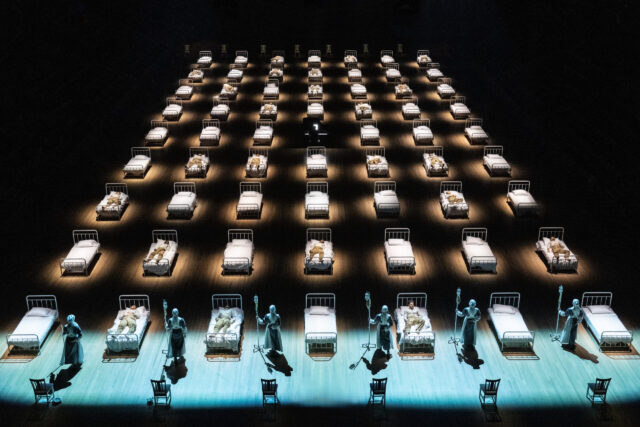

Innovative German director Guth has adapted Schwanengesang into a riveting tale of love, war, and death, set inside a military field hospital; the armory itself was built for the Seventh Regiment during the Civil War, adding a layer of reality. Michael Levine’s stunning set consists of nine rows of seven white-sheeted beds, in austere alignment, with Helmut Deutsch’s piano at the center (where one of the beds would have been, but the pianist is in no need of any kind of assistance). At the front and back are six chairs and mobile IV units for nurses. The audience sits in rising rafters on either side of the beds.

When the doors open about fifteen minutes prior to the official start time, nearly two dozen of the beds are already occupied by barefoot men in WWI-era brown pants and jacket, white shirt, and suspenders (the costumes are by Constance Hoffman); they shift in restless sleep as the nurses proceed in unison through the rows of beds and Deutsch waits patiently at his grand piano.

A seriously injured soldier faces heartbreak in Doppelganger (photo by Monika Rittershaus / courtesy of Park Avenue Armory)

Schubert did not intend for the fourteen songs to form a continuous, complete narrative, but Guth transforms it into a seamless, deeply compelling, and powerful story. The doors close and the show begins, soon focusing on an unnamed solitary individual (German-Austrian tenor Jonas Kaufmann). “In deep repose my comrades in arms / lie in a circle around me; / my heart is so anxious and heavy, / so ardent with longing,” he sings in Rellstab’s “Warrior’s foreboding,” continuing, “How often I have dreamt sweetly / upon her warm breast! / How cheerful the fireside glow seemed / when she lay in my arms.”

Rellstab’s words are beautiful and romantic as the man makes numerous references to nature while contemplating his bleak future. “Murmuring brook, so silver and bright, / do you hasten, so lively and swift, to my beloved?” he asks in “Love’s message.” In “Far away,” he speaks of “Whispering breezes, / gently ruffled waves, darting sunbeams, lingering nowhere.” Other stanzas refer to “snowy blossoms,” “slender treetops,” a “roaring forest,” “gardens so green.”

Heine’s lyrics cast the man as a lonely soul desperate for connection. “I, unhappy Atlas, must bear a world, / the whole world of sorrows. / I bear the unbearable, and my heart / would break within my body,” he proclaims. Tears figure prominently, appearing in four songs. “My tears, too, flowed / down my cheeks. / And oh – I cannot believe / that I have lost you!” he declares in “Her portrait.”

Kaufmann is in terrific voice; he wanders around the set seeking solace, looking for a reason to fight for a life that is draining from his body. He stops at a bedpost, lays out on the floor, and stands under falling rose petals. He makes sure to visit each part of the audience, sometimes coming within only a few feet. The other soldiers and the nurses weave in and out of the columns, sitting on beds or gathering together. (The movement is expertly choreographed by Sommer Ulrickson.)

Helmut Deutsch calmly plays at a center piano while action swirls around him (photo by Monika Rittershaus / courtesy of Park Avenue Armory)

Urs Schönebaum’s brilliant lighting is like a character unto itself; each bed has its own white spotlight, and occasionally a stand of lights bursts from one end, casting long shadows amid the nearly blinding brightness. The projections by rocafilm include bare trees and an abstract static on the floor, as if we’re inside the man’s disintegrating mind. Mathis Nitschke’s compositions feature sudden blasts of the noises of war, providing theatrical accompaniment to Deutsch’s gorgeous playing, all balanced by Mark Grey’s tantalizing sound design, which links songs that were not meant to mellifluously follow one after another to do exactly that, flowing like the brooks so often referenced in the lyrics.

Guth, who played Schubert’s Winterreise as a student and previously collaborated with Kaufmann on the composer’s Fierrabras, takes advantage of nearly everything the armory has to offer; it’s hard to imagine the ninety-minute Doppelganger being quite as successful anywhere else. Surtitles are projected in English and German above the seating. The cavernous fifty-five-thousand-square-foot hall has rarely felt so intimate despite its impressive length and vast, high ceiling. And the finale holds a powerful surprise that also explains the title of the work, and not just because the name of the song is “Der Doppelgänger.”

Incorporating dance, theater, music recital, art installation, and poetry, Doppelganger is a triumphant, site-specific marvel that is not just for classical music fans. It’s a timeless emotional treatise on the evils of war and the heartbreak of lost love as a man reflects on his life while staring death straight in the face.

It’s a harrowing and thoroughly astounding journey. Although it grew out of the European wars of the nineteenth century, it remains painfully relevant even as a twenty-first-century war rages on the borders of Eastern Europe today.

[Mark Rifkin is a Brooklyn-born, Manhattan-based writer and editor; you can follow him on Substack here.]