Rashomon helps kick off delayed monthlong centennial celebration of Toshirō Mifune at Film Forum

MIFUNE

Film Forum

209 West Houston St.

February 11 – March 10

212-727-8110

filmforum.org

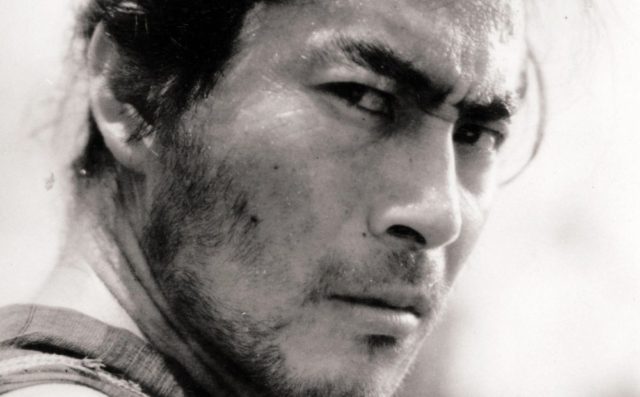

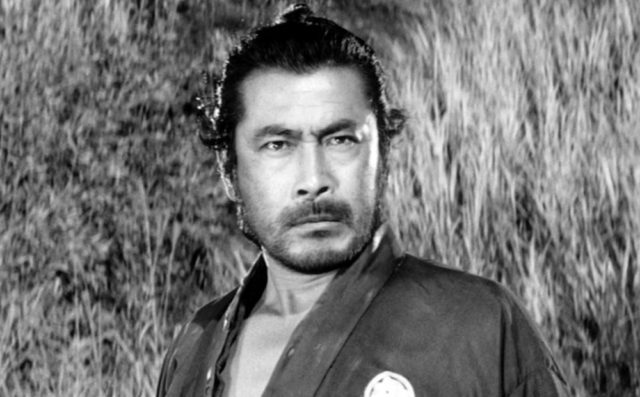

No other international actor stands out for his country as Japanese star Toshirō Mifune does for his. Quick: Name another big-time Japanese thespian. Born in Seitō on April Fools Day in 1920, Mifune made nearly two hundred appearances in films and on television, including a particularly fertile period between 1948 and 1966, when he made movies with Akira Kurosawa, Hiroshi Inagaki, Kihachi Okamoto, Masaki Kobayashi, and Mikio Naruse that would become classics. He worked in multiple genres, from Western Westerns and Eastern Westerns to noir detective thrillers, police procedurals, samurai epics — and, yes, romance.

Film Forum is celebrating Mifune’s fifty-year career and the hundredth anniversary of his birth — the series was scheduled for 2020 but was postponed because of the pandemic lockdown — with an exciting retrospective running February 11 to March 10, consisting of thirty-three films over four weeks, from his onscreen debut in 1947’s Snow Trail to all sixteen films he made with Kurosawa, from the little-seen A Wife’s Heart and All About Marriage to grandiose Shakespearean adaptations, from the Musashi Miyamoto trilogy to his fling with Hollywood. Mifune, who died on Christmas Eve, 1997, could out-Eastwood Eastwood, out-Bronson Bronson, and out-McQueen McQueen. “I’m not always great in pictures, but I’m always true to the Japanese spirit,” he once said. You can decide for yourself how great he was by heading over to Film Forum and catching a bunch of these flicks, several of which are not available for streaming; below are some recommendations.

RASHOMON (Akira Kurosawa, 1950)

Friday, February 11 at 2:55, 7:10

Wednesday, February 16, 5:35

Friday, March 4, 3:50

Saturday, March 5, 12:40

Wednesday, March 9, 6:00

Thursday, March 10, 12:40, 5:10

filmforum.org

One of the most influential films of all time, Akira Kurosawa’s 1950 masterpiece, adapted from Ryunosuke Akutagawa’s short story “In a Grove,” stars Toshirō Mifune as a bandit accused of the brutal rape of a samurai’s wife (Machiko Kyo) and the murder of her husband (Masayuki Mori). However, four eyewitnesses tell a tribunal four different stories, each told in flashback as if the truth, forcing the characters — and the audience — to question the reality of what they see and experience. Kurosawa veteran Takashi Shimura — the Japanese Ward Bond — plays a local woodcutter, with Minoru Chiaka as the priest. The mesmerizing work, which won an Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film, is beautifully shot by Kazuo Miyagawa; Rashomon is nothing short of unforgettable. (What is forgettable is the English-language remake, The Outrage, directed by Martin Ritt and starring Edward G. Robinson, Paul Newman, Laurence Harvey, Claire Bloom, and William Shatner.)

Nakajima (Toshirō Mifune) lives in fear in Akira Kurosawa’s I Live in Fear

I LIVE IN FEAR (Akira Kurosawa, 1955)

Friday, February 11, 12:40, 4:55, 9:10

Friday, February 18, 12:30

Saturday, February 19, 2:50

filmforum.org

Akira Kurosawa’s powerful psychological drama I Live in Fear, also known as Record of a Living Being, begins with a jazzy score over shots of a bustling Japanese city, people anxiously hurrying through as a Theremin joins the fray. But this is no Hollywood film noir or low-budget frightfest; Kurosawa’s daring film is about the end of old Japanese society as the threat of nuclear destruction hovers over everyone. A completely unrecognizable Toshirō Mifune stars as Nakajima, an iron foundry owner who wants to move his large family — including his two mistresses — to Brazil, which he believes to be the only safe place on the planet where he can survive the H bomb. His immediate family, concerned more about the old man’s money than anything else, takes him to court to have him declared incompetent; there he meets a dentist (the always excellent Takashi Shimura) who also mediates such problems — and fears that Nakajima might be the sanest one of all.

Toshirō Mifune and Shirley Yamaguchi face unwarranted gossip in Akira Kurosawa’s Scandal

SCANDAL (Akira Kurosawa, 1950)

Sunday, February 13, 12:40

Monday, February 14, 3:00

filmforum.org

When two famous people are caught together at a hotel in the mountains, a scandal breaks out as a lurid gossip magazine prints their picture and makes up a sordid romance that is not true. With their reputations tainted, they consider suing the publication, but they run into problems with their ragtag lawyer, who has a bit of a gambling problem. Akira Kurosawa regular Toshirō Mifune stars as Ichiro Aoye, a well-known painter who likes smoking pipes and riding his flashy motorcycle. Yoshiko Yamaguchi is Miyaka Saijo, a timid pop singer who is terrified of the unwanted publicity. And Takashi Shimura is Hiruta, the struggling lawyer devoted to his young daughter, who is dying of TB. The first half of the movie is involving right from the roaring opening-titles sequence, with good characterization and an alluring story line. Unfortunately, the film bogs down in the second half, especially during the hard-to-believe courtroom scenes, the only ones of Kurosawa’s career. And the Christmas bit is tired and cliché-ridden, even if might have been unique at the time for a film made in postwar Japan. But Kurosawa’s attack on the media is still valid today, even if he did fill it with sappy melodrama.

Takashi Shimura and Toshirō Mifune team up as detectives tracking a stolen gun in Akira Kurosawa’s Stray Dog

STRAY DOG (Akira Kurosawa, 1949)

Monday, February 14, 8:10

Friday, February 18, 2:40

Sunday, February 20, 12:40

Thursday, February 24, 5:50

Wednesday, March 9, 8:10

filmforum.org

Akira Kurosawa’s thrilling police procedural Stray Dog is one of the all-time-great film noirs. When newbie detective Murakami (Toshirō Mifune) gets his Colt lifted on a trolley, he fears he’ll be fired if he does not get it back. But as he searches for the weapon, he discovers that it is being used in a series of robberies and murders — for which he feels responsible. Teamed with seasoned veteran Sato (Takashi Shimura), Murakami risks his career — and his life — as he tries desperately to track down his gun before it is used again. Kurosawa makes audiences sweat, showing postwar Japan in the midst of a brutal heat wave, with Murakami, Sato, dancer Harumi Namiki (Keiko Awaji), and others constantly mopping their brows — the heat is so palpable, you can practically see it dripping off the screen. (You’ll find yourself feeling relieved when Sato hits a button on a desk fan, causing it to turn toward his face.) In his third of sixteen films made with Kurosawa, Mifune plays Murakami with a stalwart vulnerability, working beautifully with Shimura’s cool, calm cop who has seen it all and knows how to handle just about every situation. (Shimura was another Kurosawa favorite, appearing in twenty-one of his films.)

Rookie detective Murakami (Toshirō Mifune) often finds himself in the shadows in Stray Dog

Mifune is often seen through horizontal or vertical gates, bars, curtains, shadows, window frames, and wire, as if he’s psychologically and physically caged in by his dilemma — and as time goes on, the similarities between him and the murderer grow until they’re almost one and the same person, dealing ever-so-slightly differently with the wake of the destruction wrought on Japan in WWII. Inspired by the novels of Georges Simenon and Jules Dassin’s The Naked City, Stray Dog is a dark, intense drama shot in creepy black and white by Asakazu Nakai and featuring a jazzy soundtrack by Fumio Hayasaka that unfortunately grows melodramatic in a few key moments — and oh, if only that final scene had been left on the cutting-room floor. It also includes an early look at Japanese professional baseball. Kurosawa would soon become the most famous Japanese auteur in the world, going on to make Rashomon, Ikiru, Seven Samurai, Throne of Blood, The Hidden Fortress, The Bad Sleep Well, The Lower Depths, and I Live in Fear in the next decade alone.

The Lower Depths is another masterful collaboration between Akira Kurosawa and Toshirō Mifune

THE LOWER DEPTHS (Akira Kurosawa, 1957)

Tuesday, February 15, 2:45, 8:00

Wednesday, February 16, 12:40

Tuesday, March 1, 5:40

filmforum.org

Loosely adapted from Maxim Gorky’s social realist play, The Lower Depths is yet another masterpiece from Japanese auteur Akira Kurosawa. Set in an immensely dark and dingy ramshackle skid-row tenement during the Edo period, the claustrophobic film examines the rich and the poor, gambling and prostitution, life and death, and everything in between through the eyes of impoverished characters who have nothing. The motley crew includes the suspicious landlord, Rokubei (Ganjiro Nakamura), and his much younger wife, Osugi (Isuzu Yamada); Osugi’s sister, Okayo (Kyôko Kagawa); the thief Sutekichi (Toshirō Mifune), who gets involved in a love triangle with a noir murder angle; and Kahei (Bokuzen Hidari), an elderly newcomer who might be more than just a grandfatherly observer. Despite the brutal conditions they live in, the inhabitants soldier on, some dreaming of their better past, others still hoping for a promising future. Kurosawa infuses the gripping film with a wry sense of humor, not allowing anyone to wallow away in self-pity. The play had previously been turned into a film in 1936 by Jean Renoir, starring Jean Gabin as the thief.

Toshirō Mifune and Akira Kurosawa take on Shakespeare in Throne of Blood

THRONE OF BLOOD (Akira Kurosawa, 1957)

Wednesday February 16, 3:15

Thursday, February 17, 12:40, 8:20

Sunday, February 27, 12:40, 8:10

Sunday, March 6, 9:05

filmforum.org/film/throne-of-blood-mifune

Akira Kurosawa’s marvelous reimagining of Macbeth is an intense psychological thriller that follows one man’s descent into madness. Following a stunning military victory led by Washizu (Toshirô Mifune) and Miki (Minoru Chiaki), the two men are rewarded with lofty new positions. As Washizu’s wife, Asaji (Isuzu Yamada, with spectacular eyebrows), fills her husband’s head with crazy paranoia, Washizu is haunted by predictions made by a ghostly evil spirit in the Cobweb Forest, leading to one of the all-time classic finales. Featuring exterior scenes bathed in mysterious fog, cinematographer Asakazu Nakai’s interior long shots of Washizu and Asaji in a large, sparse room carefully considering their next bold move, and composer Masaru Sato’s shrieking Japanese flutes, Throne of Blood is a chilling drama of corruptive power and blind ambition, one of the greatest adaptations of Shakespeare ever put on film.

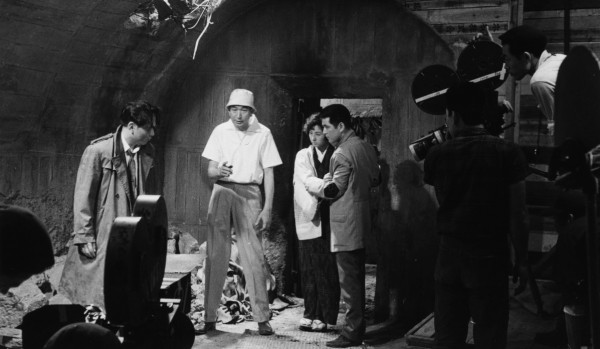

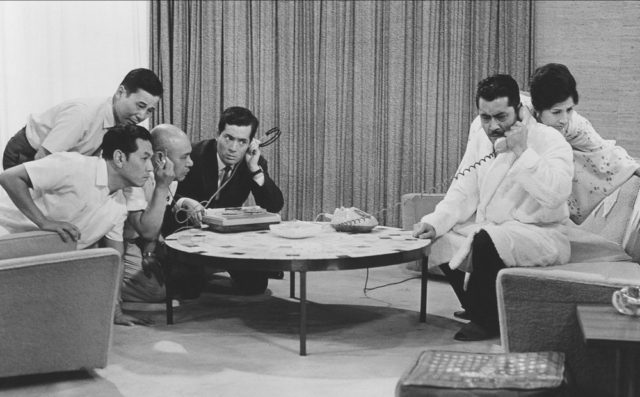

A group of men try to help Kingo Gondo (Toshirō Mifune) find kidnappers in Akira Kurosawa’s tense noir / police procedural

HIGH AND LOW (Akira Kurosawa, 1963)

Saturday, February 19, 8:00

Wednesday, March 2, 2:30

Tuesday, March 8, 12:40, 7:50

filmforum.org

On the verge of being forced out of the company he has dedicated his life to, National Shoes executive Kingo Gondo’s (Toshirō Mifune) life is thrown into further disarray when kidnappers claim to have taken his son, Jun (Toshio Egi), and are demanding a huge ransom for his safe return. But when Gondo discovers that they have mistakenly grabbed Shinichi (Masahiko Shimazu), the son of his chauffeur, Aoki (Yutaka Sada), he at first refuses to pay. But at the insistence of his wife (Kyogo Kagawa), the begging of Aoki, and the advice of police inspector Taguchi (Kenjiro Ishiyama), he reconsiders his decision, setting in motion a riveting police procedural that is filled with tense emotion. Loosely based on Ed McBain’s 87th Precinct novel King’s Ransom, Akira Kurosawa’s High and Low, photographed by longtime Kurosawa cinematographer Asakazu Nakai, is divided into two primary sections: The first half takes place in Gondo’s luxury home, orchestrated like a stage play as the characters are developed and the plan takes hold. The second part of the film follows the police, under the leadership of Chief Detective Tokura (Tatsuya Nakadai), as they hit the streets of the seedier side of Yokohama in search of the kidnappers. Known in Japan as Tengoku to Jigoku, which translates as Heaven and Hell, High and Low is an expert noir, a subtle masterpiece that tackles numerous socioeconomic and cultural issues as Gondo weighs the fate of his business against the fate of a small child; it all manages to feel as fresh and relevant today as it probably did back in the ’60s.

Toshirō Mifune and Takashi Shimura made fifty-three movies together

DRUNKEN ANGEL (Akira Kurosawa, 1948)

Saturday, February 19, 12:40

Sunday, February 27, 6:00

Monday, February 28, 12:40

Tuesday, March 1, 8:20

Wednesday, March 2, 5:50

Thursday, March 10, 2:45

filmforum.org

The first film that Kurosawa had total control over, Drunken Angel tells the story of a young Yakuza member, Matsunaga (Toshiro Mifune), who shows up late one night at the office of the neighborhood doctor, Sanada (Takashi Shimura), to have a bullet removed from his hand. Sanada, an expert on tuberculosis, immediately diagnoses Matsunaga with the disease, but the gangster is too proud to admit there is anything wrong with him. Sanada sees a lot of himself in the young man, remembering a time when his life was full of choices — he could have been a gangster or a successful big-city doctor. When Okada (Reisaburo Yamamoto) returns from prison, searching for Sanada’s nurse, Miyo (Chieko Nakakita), the film turns into a classic noir, with marvelous touches of German expressionism thrown in. We deducted a quarter star for the terrible incidental music that lapses into melodramatic mush.

Nishi (Toshirô Mifune) is desperate for revenge in Akira Kurosawa’s dark Shakespearean noir, The Bad Sleep Well

THE BAD SLEEP WELL (Akira Kurosawa, 1960)

Thursday, February 24, 2:50

Sunday, February 27, 3:00

Friday, March 4, 8:20

filmforum.org

The twelfth of sixteen films director Akira Kurosawa and actor Toshirô Mifune made together between 1948 and 1965, the Shakespearean noir The Bad Sleep Well is a tense, gripping thriller in which Kurosawa takes on post-WWII Japanese corporate culture, incorporating elements of Hamlet into the complex narrative. The 1960 film begins with a long wedding scene in which everything is set in motion, from identifying characters (and their flaws) to developing the central storylines. Kōichi Nishi (Mifune) is marrying Yoshiko (Kyōko Kagawa), a young woman with a physical disability whose father is Iwabuchi (Masayuki Mori), the vice president of Public Corporation, a construction company immersed in financial scandal as related by one of the many cynical reporters (Kōji Mitsui) covering the party and anticipating possible arrests. Also at the affair are Iwabuchi’s cohorts in crime, Miura (Gen Shimizu), Moriyama (Takashi Shimura), Shirai (Kō Nishimura), and Wada (Kamatari Fujiwara), as well as Iwabuchi’s rogue son, Tatsuo (Tatsuya Mihashi), who threatens to kill Nishi if he does anything to hurt his sister. It soon becomes clear that Nishi in fact does have more on his mind than just marrying into the company. “Even now they sleep soundly, grins on their faces,” Nishi declares. “I won’t stand for it! I can never hate them enough!”

Photographed in an enveloping, almost 3-D black-and-white by Yuzuru Aizawa and with a propulsive, jazzy score by Masaru Sato, The Bad Sleep Well is a deeply psychological, eerie tale that finds inspiration in the story of Hamlet, Polonius, Ophelia, Claudius, Gertrude, Laertes, and Horatio. But whereas Kurosawa’s Throne of Blood and Ran were more direct interpretations of Macbeth and King Lear, respectively, Kurosawa, who edited the film and cowrote it with Hideo Oguni, Eijirô Hisaita, Ryûzô Kikushima, and Shinobu Hashimoto, uses the Shakespeare tragedy more subtly as he investigates greed, envy, revenge, betrayal, suicide, torture, ghosts, and murder; in fact, many critical plot points, including those involving violence, occur offscreen. The locations are spectacular, especially a volcano and an abandoned, decimated munitions factory that clearly references the destruction wrought by WWII. The actors wear their hearts on their sleeves, often emoting with silent-film tropes, especially Shimura, Fujiwara, and Nishimura as Iwabuchi’s nervous, perpetually worried underlings and Mihashi as the wild, unpredictable prodigal son. Mifune is stalwart throughout, wearing pristine suits and eyeglasses that mask what is bubbling inside him, threatening to explode, while Mori is a magnificently evil villain. At 150 minutes, it’s a long film, but it’s worth every minute; it could have actually been longer, but Kurosawa, in his first film made through his own independent production company, instead chose an abrupt yet fascinating ending with all kinds of future implications. Made between the period piece The Hidden Fortress and the samurai Western Yojimbo, The Bad Sleep Well was advertised as “a film that will violently jolt the paralyzed soul of modern man back to its senses,” and it still does just that, as corporate corruption seems to never end. Oh, and it also features one of the best wedding cakes ever put on celluloid.

Toshirō Mifune stars as a corrupt cop in The Last Gunfight

THE LAST GUNFIGHT (Kihachi Okamoto, 1960)

Friday, February 25, 3:50, 8:40

filmforum.org

In the little-known Kihachi Okamoto yakuza noir The Last Gunfight, Toshirō Mifune stars as corrupt detective Saburo Fujioka, who has been reassigned from Tokyo to Kojin City and instantly becomes caught in the middle of a mob war between rival gangs looking to pay him off so he will work for them. He befriends Tetsuo Maruyama (Kôji Tsuruta), whose wife might have been murdered, while alternately meeting with some bad people and angering his fellow cops, who are not happy to have a bad apple on their team. Director Kihachi Okamoto has fun with clichés — guns firing at the camera, as if aimed at the viewer; newspaper headlines forwarding the plot; barroom brawls; femmes fatales; nightclub scenes with live music, but in this case performed by three hitmen, singing, “Rub ’em Out”; evil baddies who think they’re untouchable; a loud, jazzy score by Masaru Satô with strange hints of other genres; and a bland color scheme that makes you wish it was made in black-and-white. And through it all, Fujioka never loses the tie and only takes off his trench coat twice. There’s also a poignant surprise twist at the end. Based on a story by Haruhiko Oyabu, it might not be a top-of-the-line thriller, but it’s worth it just to watch Mifune strut his stuff.

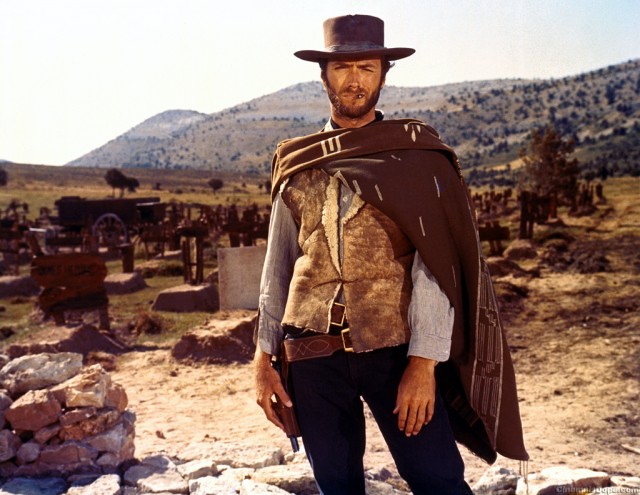

Toshiro Mifune can’t believe what he sees in Yojimbo

YOJIMBO (Akira Kurosawa, 1961)

Wednesday, February 23, 8:30

Saturday, February 26, 12:40, 5:10

Monday, February 28, 2:45

Thursday, March 3, 12:40

Tuesday, March 8, 3:30

filmforum.org

Kuwabatake Sanjuro (Toshirō Mifune) is a lone samurai on the road following the end of the Tokugawa dynasty in yet another of Akira Kurosawa’s unforgettable masterpieces. Sanjuro comes to a town with two warring factions and plays each one off the other as a hired hand. Neo’s battles with myriad Agent Smiths are nothing compared to Yojimbo’s magnificent swordfights against growing bands of warriors that include the evil Unosuke (Tatsuya Nakadai), who is in possession of a new weapon that shoots bullets. Try watching this film and not think of several Clint Eastwood Westerns (particularly Sergio Leone’s A Fistful of Dollars, since this is a direct remake of that 1964 Italian flick) as well as High Noon.

Toshirō Mifune can’t believe what he sees in Sanjuro

SANJURO (Akira Kurosawa, 1962)

Saturday, February 26, 3:00

Thursday, March 3, 3:00

Tuesday, March 8, 5:45

filmforum.org

In this Yojimbo-like tale, Toshirō Mifune shows up in a small town looking for food and fast money and takes up with a rag-tag group of wimps who don’t trust him when he says he will help them against the powerful ruling gang. Funnier than most Kurosawa samurai epics, Sanjuro is unfortunately brought down a notch by a bizarre soundtrack that ranges from melodramatic claptrap to a jazzy big-city score.

Toranosuke Shimada (Toshirō Mifune) shows rogue samurai Ryunosuke Tsukue (Tatsuya Nakadai) how its done in The Sword of Doom

THE SWORD OF DOOM (THE GREAT BODHISATTVA PATH) (Kihachi Okamoto, 1966)

Monday, February 21, 7:55

Wednesday, March 9, 3:10

filmforum.org

The Sword of Doom tells the story of one of the screen’s most brutal antiheroes, a samurai you can’t help but root for despite his coldhearted brutality, a heartless killer called “a man from hell.” Based on Kaizan Nakazato’s forty-one-volume serial novel Dai-bosatsu Tōge, Kihachi Okamoto’s The Sword of Doom, aka The Great Bodhisattva Pass, begins in 1860 with Ryunosuke Tsukue (Tatsuya Nakadai) slaying an elderly Buddhist pilgrim (Ko Nishimura) apparently for no reason as the man visits a far-off mountain grave. Shortly before Ryunosuke is to battle Bunnojo Utsuki (Ichiro Nakaya) in a competition using unsharpened wooden swords, the man’s wife, Ohama (Michiyo Aratama), comes to him, begging for Ryunosuke to lose the match on purpose to save her family’s future. A master swordsman with an unorthodox style, Ryunosuke takes advantage of the situation in more ways than one. As emotionless as he is fearless, Ryunosuke is soon ambushed on a forest road, but killing, to him, comes natural, whether facing one man or dozens — or even hundreds. The only person he shows even the slightest respect for is Toranosuke Shimada (Toshirō Mifune), the instructor at a sword-fighting school. “We have rules concerning strangers,” Toranosuke tells him, but Ryunosuke plays by no rules. “The sword is the soul. Study the soul to know the sword. Evil mind, evil sword,” Toranosuke adds, words that torment Ryunosuke, who tries to start a family in spite of his hard, detached demeanor. But regardless of circumstance, Ryunosuke continues on his bloody path, culminating in an unforgettable battle that is one of the finest of the jidaigeki genre.

The Sword of Doom boasts a memorable performance by Nakadai, the star of such other classics as Masaki Kobayashi’s Harakiri, Hiroshi Teshigara’s The Face of Another and Samurai Rebellion, and Okamoto’s Battle of Okinawa and Kill!, as well as many Akira Kurosawa films, including Yojimbo, Sanjuro, High and Low, and Ran. In The Sword of Doom he is reunited with Aratama, who played his wife in Okamoto’s masterpiece trilogy, The Human Condition. Nakadai is brilliant as Ryunosuke, able to win over the audience, riveting your attention even though he is portraying a horrible man who rejects all sympathy. Also contributing to the film’s relentless intensity are Hiroshi Murai’s gorgeous black-and-white cinematography, which features a beautiful sword fight in the snow and an exquisitely photographed scene in a claustrophobic mill, and Masaru Sato’s sparse but effective score. The Sword of Doom is a masterful tale of evil, of one man’s struggle with inner demons as he wanders through a changing world.

The first film that Akira Kurosawa had total control over, Drunken Angel tells the story of a young Yakuza member, Matsunaga (Toshirô Mifune), who shows up late one night at the office of the neighborhood doctor, Sanada (Takashi Shimura), to have a bullet removed from his hand. Sanada, an expert on tuberculosis, immediately diagnoses Matsunaga with the disease, but the gangster is too proud to admit there is anything wrong with him. Sanada sees a lot of himself in the young man, remembering a time when his life was full of choices — he could have been a gangster or a successful big-city doctor. When Okada (Reisaburo Yamamoto) returns from prison, searching for Sanada’s nurse, Miyo (Chieko Nakakita), the film turns into a classic noir, with marvelous touches of German expressionism thrown in. The terrible incidental music lapses into melodramatic mush, preventing the film from reaching its full potential greatness, but that’s just a minor quibble.

The first film that Akira Kurosawa had total control over, Drunken Angel tells the story of a young Yakuza member, Matsunaga (Toshirô Mifune), who shows up late one night at the office of the neighborhood doctor, Sanada (Takashi Shimura), to have a bullet removed from his hand. Sanada, an expert on tuberculosis, immediately diagnoses Matsunaga with the disease, but the gangster is too proud to admit there is anything wrong with him. Sanada sees a lot of himself in the young man, remembering a time when his life was full of choices — he could have been a gangster or a successful big-city doctor. When Okada (Reisaburo Yamamoto) returns from prison, searching for Sanada’s nurse, Miyo (Chieko Nakakita), the film turns into a classic noir, with marvelous touches of German expressionism thrown in. The terrible incidental music lapses into melodramatic mush, preventing the film from reaching its full potential greatness, but that’s just a minor quibble.

In Akira Kurosawa’s 1952 gem, Ikiru, winner of a special prize at the 1954 Berlin International Film Festival, the great Takashi Shimura is outstanding as simple-minded petty bureaucrat Kanji Watanabe, a paper-pushing section chief who has not taken a day off in thirty years. But when he suddenly finds out that he is dying of stomach cancer, he finally decides that there might be more to life than he thought after meeting up with an oddball novelist (Yunosuke Ito). While his son, Mitsuo (Nobuo Kaneko), and coworkers wonder just what is going on with him — he has chosen not to tell anyone about his illness — he begins cavorting with Kimura (Shinichi Himori), a young woman filled with a zest for life. Although the plot sounds somewhat predictable, Kurosawa’s intuitive direction, a smart script (cowritten with Hideo Oguni), and a marvelously slow-paced performance by Shimura (Stray Dog, Scandal, Seven Samurai) make this one of the director’s best melodramas.

In Akira Kurosawa’s 1952 gem, Ikiru, winner of a special prize at the 1954 Berlin International Film Festival, the great Takashi Shimura is outstanding as simple-minded petty bureaucrat Kanji Watanabe, a paper-pushing section chief who has not taken a day off in thirty years. But when he suddenly finds out that he is dying of stomach cancer, he finally decides that there might be more to life than he thought after meeting up with an oddball novelist (Yunosuke Ito). While his son, Mitsuo (Nobuo Kaneko), and coworkers wonder just what is going on with him — he has chosen not to tell anyone about his illness — he begins cavorting with Kimura (Shinichi Himori), a young woman filled with a zest for life. Although the plot sounds somewhat predictable, Kurosawa’s intuitive direction, a smart script (cowritten with Hideo Oguni), and a marvelously slow-paced performance by Shimura (Stray Dog, Scandal, Seven Samurai) make this one of the director’s best melodramas.

Loosely adapted from Maxim Gorky’s social realist play, The Lower Depths is a staggering achievement, yet another masterpiece from Japanese auteur Akira Kurosawa. Set in an immensely dark and dingy ramshackle skid-row tenement during the Edo period, the claustrophobic film examines the rich and the poor, gambling and prostitution, life and death, and everything in between through the eyes of impoverished characters who have nothing. The motley crew includes the suspicious landlord, Rokubei (Ganjiro Nakamura), and his much younger wife, Osugi (Isuzu Yamada); Osugi’s sister, Okayo (Kyôko Kagawa); the thief Sutekichi (Toshirō Mifune), who gets involved in a love triangle with a noir murder angle; and Kahei (Bokuzen Hidari), an elderly newcomer who might be more than just a grandfatherly observer. Despite the brutal conditions they live in, the inhabitants soldier on, some dreaming of their better past, others still hoping for a promising future. Kurosawa infuses the gripping film with a wry sense of humor, not allowing anyone to wallow away in self-pity. The play had previously been turned into a film in 1936 by Jean Renoir, starring Jean Gabin as the thief.

Loosely adapted from Maxim Gorky’s social realist play, The Lower Depths is a staggering achievement, yet another masterpiece from Japanese auteur Akira Kurosawa. Set in an immensely dark and dingy ramshackle skid-row tenement during the Edo period, the claustrophobic film examines the rich and the poor, gambling and prostitution, life and death, and everything in between through the eyes of impoverished characters who have nothing. The motley crew includes the suspicious landlord, Rokubei (Ganjiro Nakamura), and his much younger wife, Osugi (Isuzu Yamada); Osugi’s sister, Okayo (Kyôko Kagawa); the thief Sutekichi (Toshirō Mifune), who gets involved in a love triangle with a noir murder angle; and Kahei (Bokuzen Hidari), an elderly newcomer who might be more than just a grandfatherly observer. Despite the brutal conditions they live in, the inhabitants soldier on, some dreaming of their better past, others still hoping for a promising future. Kurosawa infuses the gripping film with a wry sense of humor, not allowing anyone to wallow away in self-pity. The play had previously been turned into a film in 1936 by Jean Renoir, starring Jean Gabin as the thief.

We used to think that Aki Kaurismäki’s

We used to think that Aki Kaurismäki’s