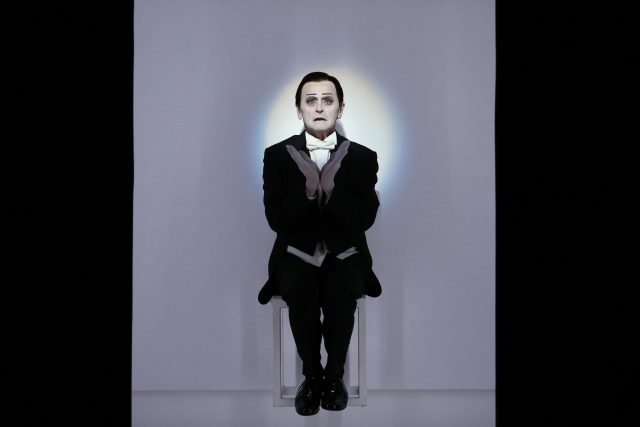

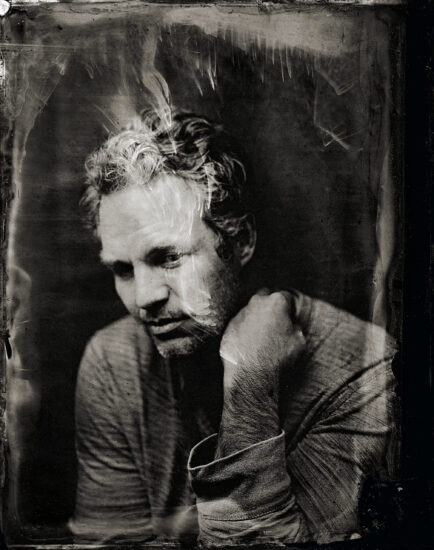

Mark Ruffalo will be joined by Jessica Hecht for reading and discussion about upcoming stage production of Ironweed and the unhoused crisis (photo by Victoria Will)

Who: Mark Ruffalo, Jessica Hecht, Vinson Cunningham

What: Play reading and discussion

Where: BAM Strong, Harvey Theater, 651 Fulton St.

When: Tickets on sale Thursday, April 18, $35+, 1:00; show is Friday, May 17, 7:30

Why: “Riding up the winding road of Saint Agnes Cemetery in the back of the rattling old truck, Francis Phelan became aware that the dead, even more than the living, settled down in neighborhoods.” So begins Ironweed, the third of eight books in William Kennedy’s Albany Cycle. The 1983 novel earned the Albany native the Pulitzer Prize and was made into a movie four years later by Hector Babenco starring Oscar nominees Jack Nicholson as Francis and Meryl Streep as Helen Archer, a homeless couple just trying to make it to the next day.

The story is now being told in a new play, along with an all-star audio recording of the drama, directed by Jodie Markell. On April 18 at 1:00, tickets go on sale for “Ironweed: An Evening of Art & Humanity,” which consists of a staged reading of several scenes from the play, with Mark Ruffalo and Jessica Hecht as the couple, followed by a discussion with the actors and experts on the unhoused crisis, moderated by Vinson Cunningham. The audio recording features Ruffalo, Hecht, Norbert Leo Butz, Kristine Nielsen, John Magaro, Michael Potts, David Rysdahl, Frank Wood, Katie Erbe, and others, the ninety-six-year-old Kennedy as narrator, songs by Tom Waits, and an original score by Tamar-kali.

Ruffalo is on the board of the Solutions Project, which “funds and amplifies climate justice solutions created by Black, Indigenous, immigrant, women, and communities of color building an equitable world.” Hecht is the cofounder of the Campfire Project, which “promotes arts-based wellness in refugee spaces and empowers refugees to step into the spotlight, explore their creativity, and refocus on their humanity,” and she is on the board of Projects with Care, an organization that “works closely with housing and social service agencies in New York City to coordinate need-based initiatives for families who need a helping hand.”

[Mark Rifkin is a Brooklyn-born, Manhattan-based writer and editor; you can follow him on Substack here.]

The Coen brothers honor and subvert the Western as only they can in The Ballad of Buster Scruggs, a six-part anthology film they made for Netflix. It also was shown in two theaters for a week — making it eligible for Oscars — and is having a special screening on November 29 at the Museum of the Moving Image. Over the course of the last quarter-century, Joel and Ethan Coen wrote a handful of short movies that they thought would never get made, but they eventually decided to put them together into one omnibus film. Each segment tackles a different subgenre, involves at least one death, and begins with the turning of pages in an illustrated book, as if these are old classic Western fables, although that’s just a cinematic conceit: Only “The Gal Who Got Rattled” and “All Gold Canyon” were inspired by real works, by Stewart Edward White and Jack London, respectively.

The Coen brothers honor and subvert the Western as only they can in The Ballad of Buster Scruggs, a six-part anthology film they made for Netflix. It also was shown in two theaters for a week — making it eligible for Oscars — and is having a special screening on November 29 at the Museum of the Moving Image. Over the course of the last quarter-century, Joel and Ethan Coen wrote a handful of short movies that they thought would never get made, but they eventually decided to put them together into one omnibus film. Each segment tackles a different subgenre, involves at least one death, and begins with the turning of pages in an illustrated book, as if these are old classic Western fables, although that’s just a cinematic conceit: Only “The Gal Who Got Rattled” and “All Gold Canyon” were inspired by real works, by Stewart Edward White and Jack London, respectively.

New York, New York meets

New York, New York meets

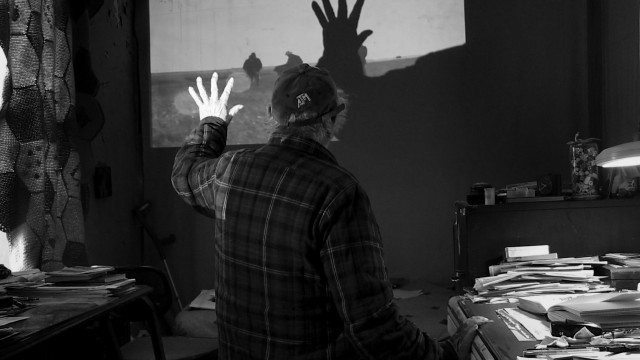

“I hate these fucking interviews,” innovative, influential, ornery, and iconoclastic photographer and filmmaker Robert Frank says while preparing to be interviewed in 1984; the scene is shown in Laura Israel’s new documentary, Don’t Blink — Robert Frank. “I’d like to walk out of the fucking frame,” he adds, then does just that. But in Don’t Blink, Frank finds himself walking once more into the frame as Israel, his longtime film editor, attempts to get him to open up about his life and career. Born in Zurich in 1924, Frank immigrated to the United States in 1947, became a fashion photographer, and had his artistic breakthrough in 1958 with the publication of the controversial photo book The Americans, which captured people unawares from all over the country, using no captions, just image, to get his point across. (In 2009,

“I hate these fucking interviews,” innovative, influential, ornery, and iconoclastic photographer and filmmaker Robert Frank says while preparing to be interviewed in 1984; the scene is shown in Laura Israel’s new documentary, Don’t Blink — Robert Frank. “I’d like to walk out of the fucking frame,” he adds, then does just that. But in Don’t Blink, Frank finds himself walking once more into the frame as Israel, his longtime film editor, attempts to get him to open up about his life and career. Born in Zurich in 1924, Frank immigrated to the United States in 1947, became a fashion photographer, and had his artistic breakthrough in 1958 with the publication of the controversial photo book The Americans, which captured people unawares from all over the country, using no captions, just image, to get his point across. (In 2009,