Nikolai Yezhov (Zach Grenier) and Isaac Babel (Danny Burstein) begin a dangerous friendship in Describe the Night (photo by Ahron R. Foster)

Atlantic Theater Company

Linda Gross Theater

336 West 20th St. between Eighth & Ninth Aves.

Tuesday – Sunday through December 24, $51-$86.50

866-811-4111

atlantictheater.org

At the beginning of Rajiv Joseph’s extraordinary Describe the Night, Isaac Babel (an almost unrecognizable Danny Burstein), a military journalist covering the Polish-Soviet War in 1920, has stopped in the Polish countryside and says to himself, “Describe the night . . . Describe the air . . . Describe the field . . .” as he unsuccessfully tries to capture their essence in his diary. He is soon joined by Russian captain Nikolai Yezhov (Zach Grenier). “The night. Describe it,” Isaac says. “Why?” Nikolai asks, dumbfounded. Isaac explains, “I just described it in my journal. I’m wondering how you would describe it. And if we both describe the same thing at the same time, will one of our descriptions be more true than the other?” Joseph’s follow-up to Guards at the Taj and Bengal Tiger at the Baghdad Zoo is a glorious, difficult-to-describe work that searches for the truth amid many lies, melding fact and fiction in creating a wildly unpredictable, endlessly adventurous tale that is as historical as it is contemporary. (At one point, a character says, “Go ahead, write your fake news story.”) The swiftly moving 165-minute play is told in three acts of four scenes each, featuring such titles as “Lies,” “Fate,” “Blood,” “Asylum,” and “Freedom,” shifting back and forth between 1920, 1937, 1940, 1989, and 2010, from Smolensk to Moscow to Dresden. As Isaac becomes a successful and well-respected writer, he maintains an odd friendship with Nikolai, who rises in the ranks of Stalin’s secret police; Isaac also has an extra-close relationship with Nikolai’s wife, Yevgenia (Tina Benko). Meanwhile, in 1989 Dresden, Russian KGB agent Vova (Max Gordon Moore) is determined to not let young Polish immigrant Urzula (Rebecca Naomi Jones) defect to the West, for both personal and political reasons. And in 2010, a plane flying from Poland to Russia to honor the seventieth anniversary of the Katyn Massacre in WWII crashes in Smolensk, setting journalist Mariya (Nadia Bowers) on the run, where she encounters young Feliks (Stephen Stocking), who just wants to avoid trouble. Through the years, various characters and their stories intersect in unexpected ways as Isaac’s diary makes its way around the world.

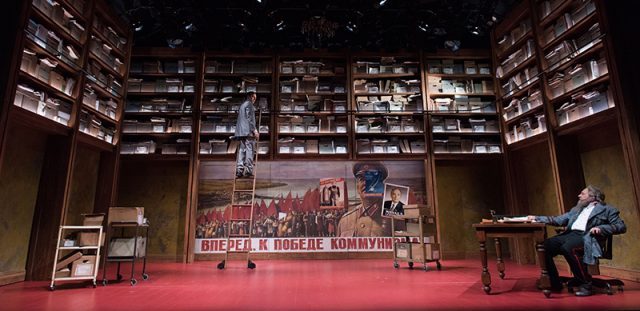

Rajiv Joseph’s Describe the Night climbs high at the Atlantic (photo by Ahron R. Foster)

Continuing at the Atlantic through December 24, Describe the Night is a gorgeously ambitious play, continually challenging the audience with its unconventional twists and turns. Director Giovanna Sardelli, who has previously collaborated with Joseph on Archduke and Guards at the Taj, brilliantly navigates through the multiple time periods and Tim Mackabee’s mostly simple but effective changing sets. Six-time Tony nominee Burstein (Fiddler on the Roof, The Drowsy Chaperone) is gentle and touching as Isaac, a man who believes that his principles will triumph over tyranny; Tony nominee Grenier (33 Variations, The Good Wife) is an excellent counterpoint, loud and blustery as Nikolai, a proud but uncomplicated man who is able to overlook friendship when necessary for the sake of the party. Benko (Scenes from a Marriage, Desdemona) excels as the strangely mysterious Yevgenia, while Stocking (Archduke, Dance Dance Revolution) embodies all of our everyday fears with an intense quirkiness. The Playbill comes with an extra sheet that details the true stories of Isaac, Nikolai, Yevgenia, and the Smolensk crash; be sure not to read it until after the show to fully appreciate the artistic license Joseph takes in transforming this tale into so much more. “You’re a media person, and so you you you love to make up stories that are more interesting than what the truth is and what the truth is that sometimes planes try to land in a heavy fog over a forest and then hit trees and crash,” Feliks tells Mariya. So how to succinctly describe Describe the Night? Truthfully, it’s indescribable.