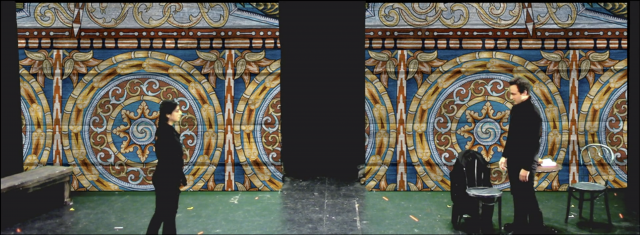

Austin Pendleton is revisiting Orson’s Shadow for its twenty-fifth anniversary (photo by Jonathan Slaff)

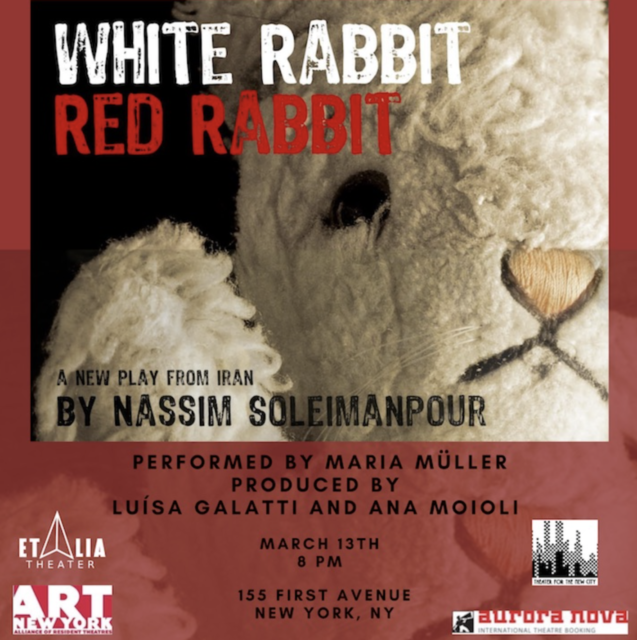

ORSON’S SHADOW

Theater for the New City

155 First Ave. between Ninth & Tenth Aves.

Wednesday – Sunday through March 31, pay-what-you-can – $25

212-254-1109

www.theaterforthenewcity.net

In 1960, Orson Welles directed the first English-language adaptation of Eugene Ionesco’s fascist parable, Rhinoceros, with a cast that included Laurence Olivier and his soon-to-be third wife, Joan Plowright, as Olivier’s marriage to Vivien Leigh fell apart. It was a scandal-ridden, problematic production that would be Welles’s theatrical swan song.

In 2000, writer, director, actor, and teacher Austin Pendleton’s Orson’s Shadow opened at Steppenwolf in Chicago, a fictionalized behind-the-scenes foray into the making of that show, with actors portraying Olivier, Plowright, Leigh, Welles, critic Kenneth Tynan, and a stagehand named Sean. The play was directed by up-and-comer David Cromer.

Pendleton is revisiting Orson’s Shadow for its twenty-fifth anniversary, codirecting a slightly tweaked version at Theater for the New City, presented in association with Oberon Theatre Ensemble and Strindberg Rep. Pendleton’s play focuses on ego and legacy, the stage and the silver screen, things that the Tony winner is eminently familiar with; he has more than 160 television and film credits (My Cousin Vinnie, Homicide, Oz, Law and Order, Finding Nemo, The Muppet Movie, Catch-22) and nearly five dozen theater credits for acting and directing (Fiddler on the Roof, The Little Foxes, The Diary of Anne Frank, Between Riverside and Crazy, Life Sucks.). In 2007, he received a Special Drama Desk Award as “Renaissance Man of the American Theatre,” and his continuing legacy was celebrated in the 2016 documentary Starring Austin Pendleton.

During a wide-ranging Zoom talk that was scheduled for fifteen to thirty minutes but lasted an hour and a half, Pendleton, a true New York City raconteur who was born in Warren, Ohio, and turns eighty-four this week, discussed his superstar-filled life and career sans ego as he shared stories about working with Welles, Jerome Robbins, Lynn Redgrave, Mike Nichols, Tracy Letts, Victor Mature, and Frank Langella, among countless others. And this is only the first part of the interview; look for twi-ny’s Substack post later this week, in which Pendleton does a deeper dive into Fiddler on the Roof and Tennessee Williams.

twi-ny: In the documentary Starring Austin Pendleton, Ethan Hawke says the following about you: “If this guy didn’t look the way he looks — he’s got a stutter, he’s five-whatever-he-is, he’s a funny-looking guy, and his hair’s all screwy — he’d be Marlon Brando.” What do you think of that description?

austin pendleton: Well, anything Ethan says, I take to heart, yeah. I’ve known him for years and years.

twi-ny: You have more than two hundred television, film, and theater credits. You’ve been teaching at HB Studio since 1968, and you’ll be turning eighty-four next week.

ap: That’s right.

twi-ny: Were you born with this energy? Have you ever slowed down in your entire life?

ap: No, I never have.

twi-ny: How come? What gave you that drive?

ap: Well, let’s see. I was born into a household where my mom had been a professional actress. And then she decided to give up the profession. And you know why? Well, in the mid-1930s, she got offered a very flashy part of one of the young girls in Lillian Hellman’s play The Children’s Hour. You know that play, right?

twi-ny: Yes.

ap: And all the students in there, some of them are, you know, those are flashy parts. And she got one of them for the national tour. My dad had already proposed to her once, but she wanted to pursue a professional career, because things were looking up.

That tour of The Children’s Hour was canceled when a lot of the cities realized that the play contained a compassionate portrait of a lesbian. They wouldn’t allow it in their cities.

And then my dad proposed again, and she thought, You know, what the hell? I mean, this is no way to spend one’s life. So they got married in 1938. I was born in 1940. My younger brother was born exactly a year and a half later; my birthday is March 27, his is August 27. And then after the war, my sister was born. She lives up on a farm in the Boston area, a town called Lincoln, Mass. I go up and spend a week at her farm a few times a year.

twi-ny: You’re still very close.

ap: Oh, yeah, we’re very close. Yeah. And so then, two or three years after the war, some of the people in town — the town was Warren, Ohio — came to my mom and said they wanted to start a community theater.

The county that Warren is in in Ohio is Trumbull County, so they were calling it Trumbull New Theatre. In other words, TNT. And so the first few plays were rehearsed in our living room at night after dinner.

My brother and I after dinner would set up all the furniture in the living room to conform to the needs of the play. And then we would sneak down once the rehearsal began — we were supposed to be in bed — and watch those evening rehearsals. I was just smitten.

And that’s how I got obsessed with theater. Around that time, when I was about eight or nine years old, I developed a stutter. It got a lot worse in my teenage years. But I found that when I was acting, it didn’t happen. It was fascinating. Or it happened way less and less, how shall I say, significantly. So I was free of it pretty much a lot of the time, all through my teenage years and into my twenties.

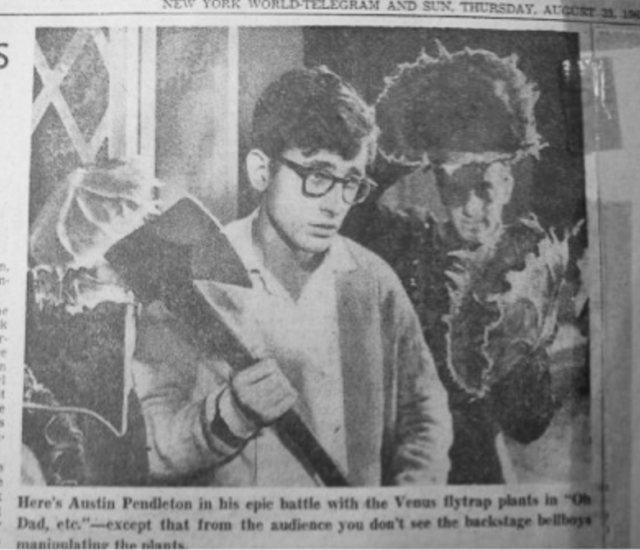

I acted in big parts in college and all that. Then, as fate would have it, the first professional job I had when I got to New York was a play called Oh Dad, Poor Dad, Mamma’s Hung You in the Closet and I’m Feelin’ So Sad [A Pseudoclassical Tragifarce in a Bastard French Tradition], in which the character has a stutter.

The guy who auditioned me for it was the director Jerome Robbins.

Austin Pendleton played Jonathan Rosepettle in Arthur Kopit’s Oh Dad, Poor Dad, Mamma’s Hung You in the Closet and I’m Feelin’ So Sad (photo courtesy of Arthur Kopit Papers, Fales Library, NYU)

twi-ny: I’ve heard of him.

ap: Yes, right. I read, and I auditioned for it fluently. The character speaks where he’s beginning sentences over and over again, but Jerry, who had never heard of me, of course, was impressed with the audition.

Afterward he said, Do you stutter? And I said, Well, yeah, but I’ve been in college shows and I’m fine. And he said, No, I was just curious. I’m wondering, how did he pick up that I actually stuttered?

I played it for a year. Some nights would be fine. Some nights it was okay. Some nights I would have a real problem with the stutter. And sometimes I’d have a severe problem with the stutter, and it was driving me crazy. So when that started to happen, I went to Jerry’s apartment, which is two blocks south from where I am right now. He was on East Seventy-Fourth between Lex and Third. The first audition I did was great.

Then I did a callback and the callback was just awful, not in terms of the stutter, just in terms of acting. When I auditioned for plays in college, they didn’t have callbacks. And, of course, in a callback the part is yours to lose.

I did a terrible callback. And so Jerry called me back the next day and said, What happened? And I decided to go for the truth. And I said, I didn’t know what I was doing anymore.

He said, Fine, I’ll just keep auditioning you. So six auditions, and I was beginning to give up. They improved, but they didn’t come anywhere near that first audition.

twi-ny: If they’re giving you six auditions, they’re obviously interested.

ap: Well, Jerry was famous for this. In fact, there’s an equity rule that was established later, unofficially known as the Jerry Robbins rule, in which after a certain number of auditions, the actor has to be paid to audition, because he would he would audition people a lot of times.

But also he kept auditioning me for this, because he wanted to see if I could get back to the excitement of the first audition. So I went home for Christmas finally. There was an agency that had set me up for the part, an agency I got with a friend who I’d made at the Williamstown Theatre Festival, where I’d been an apprentice.

The agency called me the day after Christmas and said, He wants to see you again. And I said, Oh, what’s the point? I don’t know how to get back to when it was really good. I just think I’d like to stay through January, here in Warren, Ohio, and chill with my friends. The lady from the Deborah Coleman agency said, So I’m to let Jerome Robbins know that you would rather chill with your friends in Warren, Ohio.

I said, Okay, you win. I flew back the next morning to New York. At that point, I roomed with about eight people on the Upper West Side, who I knew either from Warren or from college.

I went to audition, and there to read the first big scene between the boy and the girl, if you know the play, was Barbara Harris.

It soared, and we both got the parts that day. This was only a little over two weeks before rehearsals began. The mother was cast during that time, Jo Van Fleet.

twi-ny: That’s quite an auspicious beginning.

ap: Yeah, I mean, Jo Van Fleet and Barbara Harris, they were two of the best things in town.

twi-ny: Did the trouble you had over those six auditions have anything to do with your trying to control the stutter?

ap: No, it was just bad acting.

twi-ny: But then you’re with Barbara Harris and you shined.

ap: Well, I must say, anybody who couldn’t shine with Barbara Harris should have reexamined their career. So we got the parts two weeks before rehearsals. We were going to begin rehearsals on a Monday. On the Saturday night before the Monday, Barbara was staying in an apartment that some friends of hers had, because she didn’t know whether she’d be going back to Chicago or not.

She invited me to come over, and we worked on the two long scenes the boy and the girl have. My first really great acting lesson was with her that evening. Still, every time I pass the building, I kiss my hand and put it on the wall. It was on East Seventy-Fourth Street between Second and First. I did two shows there, each of which ran a long time. Oh Dad, Poor Dad, and then a musical by Gretchen Cryer and Nancy Ford called The Last Sweet Days of Isaac.

twi-ny: Right.

ap: That was there for about a year and a half. So I spent a long time at that theater, but it was torn down years ago.

twi-ny: You’re still in that neighborhood.

ap: Yeah. I still wander over there hoping the theater has somehow reappeared.

The other thing that happened was that every year during the mid-1940s, in the late 1940s, there would be a new touring company of Oklahoma! And my parents would take me, even though they were all evening shows and I was quite young.

twi-ny: Would it just be you or would your brother and sister go too?

ap: No, no, just me. And I was entranced by Oklahoma! I still am. There’s a route between Cleveland and Warren called Route 422. I remember you pass a lot of farms. I remember the moon shining down on one farm, at around midnight. On the way back from Cleveland, I remember making a vow then that I was going to be an actor.

twi-ny: Did you see the Oklahoma! that Daniel Fish did a few years ago?

ap: Oh, I loved that.

twi-ny: So did I. I wrote extremely favorably about it. The only negative comment I got online was from Oscar Hammerstein III. He was not happy with the whole production.

Barbara Blier, Barbara Maier Gustern, and Austin Pendleton performed cabaret together (photo by Maryann Lopinto)

ap: Oh, I thought it was brilliant. I think Hammerstein himself would have loved it, because he was extremely innovative. The woman who was the musical director, the musical coach for the singers, a couple of years ago, almost right now, got murdered.

twi-ny: I remember that.

ap: Barbara Maier Gustern.

twi-ny: In February 2020, my wife and I attended her eighty-fifth birthday party, a beautiful tribute to her held at Joe’s Pub. [ed. note: If Music Be the Food of Love, with Justin Vivian Bond, Taylor Mac, Diamanda Galas, Debbie Harry, Penny Arcade, John Kelly, and many others.

ap: I’m involved with a cabaret that we do three or four times a year, almost always down at Pangea on lower Second Avenue, and we had just had a rehearsal at Barbara’s apartment on West Twenty-Eighth, and she was performing in the cabaret as well. She was so excited that night. She went out to the street to hail a cab to get to Joe’s Pub, where one of her students was singing, and this terrible woman who was in a bad mood saw her across the street and pushed her hard down on the ground.

And the other Barbara, Barbara Bleier, who’s also in the cabaret, we were sitting in the outer lobby of her building. Happily a young man came along and found her and picked her up.

We were waiting for a car for Barbara Bleier to go home, and in walks Barbara Maier Gustern, her face covered in blood. We called an ambulance and the police came.

twi-ny: It was just a horrible, horrible thing.

ap: It was just this young woman who was in a bad mood, who comes from wealth. She just had an argument with her fiancé, who now of course is her ex-fiancé, and she was in a bad mood and she saw this woman across the street. She just crossed the street; they’d been in a little park on the block that Barbara Maier Gustern lived on, and the park had to be closed at 8:30, and our rehearsal ended at about 8:30. This woman got mad at the cop and so she was walking and she saw a lady walking across the street.

twi-ny: It was so random.

ap: It was terrible. I still haven’t gotten over it. The woman has been sentenced to eight or nine years.

twi-ny: You’ve been teaching at HB Studio now since 1968. With all the changes in theaters and technology and TV and streaming, are the students the same as they’ve always been or are they very different in their approach to theater these days?

ap: No. I basically teach what I learned from Uta Hagen and Herbert Berghof and Bobby Lewis. I was in a thing called the Lincoln Center Training Program, 1962–63. A whole lot of people auditioned and they picked thirty of us. The first day in September the producer, Bob White, had told us that at the end of the eight months, fifteen of us would be picked to go into the company, which was going to begin the following fall with Elia Kazan.

For a lot of the students, those eight months, which were for free, were very tense. I find I didn’t really care. I just was so happy to have the free training. When they picked the fifteen, one person they did not include was Frank Langella. I mean, I couldn’t follow the pattern of who they took and who they didn’t take. But it was a great eight months and Bobby Lewis was a great teacher, a great, great teacher. And the movement teacher was no less than Anna Sokolow.

twi-ny: Okay, so you have this history of working with amazing actors, directors, and teachers. Let’s talk about Orson’s Shadow, a play about theater, with Orson Welles, Laurence Olivier, Vivien Leigh, Joan Plowright, and Kenneth Tynan. You were asked to write the play by Judith Mihalyi, René Auberjonois’s wife.

ap: That’s right.

twi-ny: Then he decided he didn’t want to do it.

ap: No, no, no, no, no, no, no. What happened was that he was all set to do it, and then I got an offer from the company I’m a member of in Chicago, Steppenwolf, to do it. It needed to be in a small theater. The play always needs to be done in a small theater. And they had a small theater available. They had a policy that it had to be performed by ensemble members, but they were willing to forego that. They said that we could do it in the small theater with René and with Alfred Molina, who was to play Orson.

But then René and Alfred were not available. So we went ahead. The artistic director at Steppenwolf at the time was a woman by the name of Martha Lavey. She got for me the director David Cromer. She said, Can I show him the script? And if he likes it, can you talk to him? He read it and liked it. I got on the phone with him and I liked him immediately. I said to Cromer, You cast it in Chicago with any actors you want.

As it happened, they weren’t any from Steppenwolf, but they were good Chicago actors. We did it there, and it was a big success. Ben Brantley, who was then the New York Times critic, came out for a round-up of Chicago theater, and he wrote a great deal in that round-up about Orson’s Shadow.

Then all kinds of New York producers got interested, but none of them particularly wanted Cromer as the director. It happened that at the time we did the show at Steppenwolf, my friend Cherry Jones was in a show that was on the way to New York. We would have breakfast a lot, and she said when she read the reviews, Look, they’re going to try to change the personnel. Don’t let them do it. She said, I’ve been involved with shows like that out of town. They’re a big success. And then when the New York production is being considered, they want to go with big names.

I held out for Cromer for four years. All these producers, they had other things in mind. After four years, I went one night to see a play by Tracy Letts at the Barrow Street Theatre, Bug. The producer who had a lease at the theater, Scott Morfee, was there when I was picking up my tickets; he came out from the box office, which was sort of his office.

He came into to the lobby and said, Tracy tells me you have a play. I said, Yeah. He said, Can I read it? So he read it. The run of the bug play had just begun, toward the beginning of 2004. He said, Well, I think this play of Tracy’s is going to run at least till the end of the year. Can you wait? I said, Yes, I can certainly wait. He said, Now, are you serious about this Cromer thing?

I said, Well, let me put it this way. If you don’t hire David Cromer to direct this play, I will sulk. He said, Oh, that scares the shit out of me. OK, Cromer it is. I said, I’d love to have the Chicago cast too, because among the perceptive things that Ben Brantley said is that it should be played by actors who are not known to the audience. It shouldn’t be stars playing stars. And it should be in a small theater, have an informal feeling. The only actor who was not able to come in from Chicago was the actor playing Kenneth Tynan, the critic. So Tracy took over that part. And Tracy, of course, he’s a rock star. It did us no harm that an actor that charismatic was playing a critic. It was quite well received. It opened very early in 2005 and closed on New Year’s Eve.

twi-ny: And now, of course, everybody’s clamoring to have David Cromer direct their show.

ap: Yeah. He often thanks me for this. And I said, Cromer, thank you for thanking me, but it wasn’t a great gesture I was making. It was raw self-interest. I mean, you were the director for the show.

twi-ny: He’s been doing shows at Barrow Street ever since.

ap: He did that for quite a few years. But then Scott, after a while, lost his lease. But by that point, Cromer was directing all over town. And of course, he directed The Band’s Visit.

twi-ny: And you were recently on Broadway with Tracy in The Minutes.

ap: Yeah, right. So I owe a great deal to Tracy Letts.

twi-ny: We all do.

ap: Exactly. He’s an amazing actor, an amazing playwright, an amazing guy.

twi-ny: And his wife is amazing as well.

ap: Oh, Carrie [Coon]. Yeah, absolutely.

twi-ny: So here you are now, bringing Orson’s Shadow back to New York for its twenty-fifth anniversary, and this is the first time in your career that you’re directing your own play.

ap: I decided as the rehearsal time approached that I didn’t want to be the only director of it. I wanted somebody else there too. I have a friend named David Schweizer, who directed the New York premiere of one of my other plays, Booth, about the Booth family. He directed the original New York production of that play with Frank Langella. He’s a terrific director, and he’s become a good friend over the years. So I asked Oberon, I said, Okay, I have a codirector, David Schweizer, and actually he’s the director. I sit around, I throw out the odd note to the actors and all that. And I have conversations with them. But in terms of what a director ordinarily does, it’s David Schweizer.

twi-ny: Why have you never directed any of your plays before?

ap: I like to see another director’s perspective.

twi-ny: That makes sense.

ap: And I don’t fully trust myself.

twi-ny: I’m always so impressed by the projects you take on, as actor or director. You take a lot of chances, you go to tiny theaters, in experimental works, famous works.

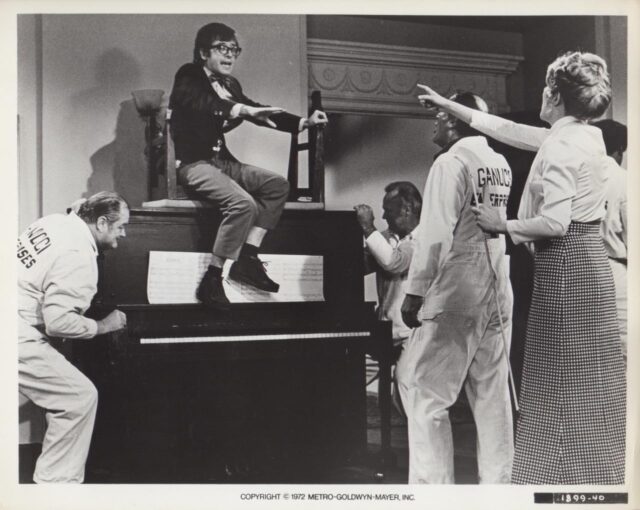

Austin Pendleton and Lynn Redgrave starred in Cy Howard’s 1972 comedy Every Little Crook and Nanny

ap: Let me tell you a story about Lynn Redgrave. I did a movie with her, a comedy, just after I made What’s Up, Doc? I had never met her before. It was called Every Little Crook and Nanny, with Lynn and me and Victor Mature and Paul Sand. So three comic actors, but the one who had the most sure grasp of comedy in the movie, and we all agreed on this, was Victor Mature, who was also a wonderful person.

twi-ny: He’s not known for his comic chops.

ap: No. I think the last two films he made employed him as a comedian. And you suddenly realize, the industry realized, Wait, we’ve been missing out on something. I mean, he gave a lot of wonderful performances. But anyway, he was a great guy, and so that’s how I knew Lynn.

A few years later, I directed her in a Chicago production of Misalliance, the Shaw play, with Lynn and Irene Worth and Bill Atherton and Donald Moffat. It was a huge hit in Chicago and there was thought of moving it to New York, among other people by Ted Mann at Circle in the Square. So one afternoon Lynn Redgrave and I had a meeting with Ted Mann about the possibility of that production coming to his theater.

That was the day, the afternoon of which we had this meeting, when I got what I hope will remain the worst review as an actor from the New York Times that I’ll ever have. It was a production of Waiting for Godot, which was particularly difficult because I had played the same part twenty years before when I was an undergraduate at Yale, and it was so successful. That’s what impelled me to come to New York and pursue this career.

It was directed by the assistant to Beckett, who had assisted Beckett in the German production, a very sweet guy by the name of Walter Asmus. He directed the way that Beckett apparently always directed actors, down to every little detail, and I totally froze up in those rehearsals. Walter Asmus was the soul of patience, but I opened catastrophically in it.

The day after it opened the review came out in the morning in the Times, which I heard was a disaster. I didn’t read it for a year but it was horrible and it was accurate.

[ed. note: The show ran at BAM in 1978 and starred Sam Waterston as Vladimir, Pendleton as Estragon, Michael Egan as Pozzo, and Milo O’Shea as Lucky.]

ap: So I had that meeting that afternoon with Lynn and Ted Mann, and after she said, Come to the Russian Tea Room, we have time before you have to go to Brooklyn. Let me buy you a bowl of soup.

My agent has me writing a memoir and it begins with this story.

We went to the Russian Tea Room and we ordered. She said, I read the review, and I thought, Oh. She said, You’re not going to be offered a professionally significant acting job for seven years. She was correct down to the number of years. But what you have to do in the meantime is go anywhere to act. So when you do get another opportunity, seven years from now . . .

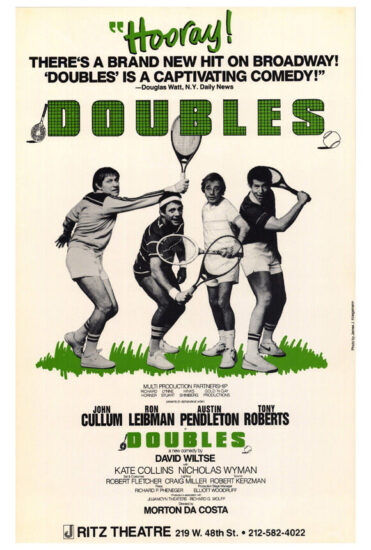

I just started acting everywhere, in showcases, in attics. My good friend, who then ran the Williamstown Theatre Festival, Nikos Psacharopoulos, would have me up there and put me in plays. I just kept acting continually for seven years and then I finally got a part in a play on Broadway by the name of Doubles about four guys [Pendleton, John Cullum, Ron Leibman, and Tony Roberts] who meet every week or a month or something to play tennis.

twi-ny: I remember when my parents saw that. They came home and gave me the signed Playbill and said that they’d just seen naked men onstage.

ap: That’s right. Yeah. Lynn Redgrave came to the opening night party. She couldn’t see the show — she was in something else — but she came to the party just to make sure everything was all right.

She had said, In England, people like my father [Sir Michael Redgrave] or John [Gielgud] or Ralph [Richardson] would get reviews as bad as the one you got this morning.

In fact, I looked up some of those reviews in a book, a collection of reviews by Kenneth Tynan. And they were pretty awful. Lynn said, in London, those reviews are forgiven. It’s always assumed the actors will be on the London stage again the following fall. But New York doesn’t forgive a review like this. So it’ll be seven years.

twi-ny: So you’re keeping yourself busy, taking all the jobs you can.

ap: Yeah, right. So in 1969, I was in the movie Catch-22, and all my scenes were with Orson Welles.

twi-ny: You played his son-in-law.

ap: Yeah.

twi-ny: He was the brigadier general, and you were the sycophantic lt. col. who he yelled at all the time.

ap: That’s right. He was fascinating and delightful on the set, but he was also a son of a bitch. He was really trying to undercut the director, Mike Nichols; he went in front of the cast, and he would instruct Mike Nichols about comedy. I mean, what can I say?

twi-ny: Nichols and May.

ap: I had worked with Mike Nichols by this point twice, once in a stage production of The Little Foxes that he directed and once under his direction of Catch-22.

twi-ny: Essentially, Orson is in charge.

ap: He just took over all our scenes. We would rehearse them, and when we were about to shoot them Orson would announce to everyone in the scene, in front of Mike, that Mike didn’t understand comedy. He wanted to play it a different way. And Mike would say, Well, if we could just try it once or twice the way I asked. Orson would do that, but he would blow lines so the takes couldn’t be used.

twi-ny: Wow.

ap: So he murdered that movie because those scenes were the comic high points of the screenplay. The screenplay was by Buck Henry, so those scenes were really funny.

twi-ny: And Buck was in the movie as well.

ap: Yes, he was in those scenes.

twi-ny: So they were all ruined.

ap: Yeah. The movie was being shot in Mexico, kind of out in the desert. The press all came down, because it was really the most anticipated movie adapted from a novel [by Joseph Heller] since Gone with the Wind. And I made a few snide remarks.

Then, after the two weeks I was there shooting, I came back to New York. The talk on Orson had always been that he made Citizen Kane, and all the movies after that were a decline. Well, it was the days of the revival houses in New York, so I began to see some of those movies that came after Kane.

And I felt really bad because I thought, These are magnificent movies, like every single one of them.

twi-ny: One after another. The Lady from Shanghai. Touch of Evil.

ap: The Magnificent Ambersons. All the Shakespeare films. And they’re compromised, you know. So I felt bad. Then, almost thirty years after we were making Catch-22, I was shooting a film in LA, and Judith Auberjonois asked me over to the house for breakfast, and she said, In 1960, Orson Welles directed Laurence Olivier in a production of Rhinoceros by Ionesco, and by the time the play opened, Orson was no longer the director; write a play about it. It was clear that she wanted me to write the role of Olivier for her husband.

I thought, I can’t do this. But the night before, I was at Schweizer’s house in LA. He had been given two copies of the biography of Orson by Simon Callow, and he gave me one of them. That happened the night before I was called over to Judith and René’s.

A couple of days later, we went upstate. I was making another Jonathan Lynn film, Trial and Error. We were up in some small town, sitting in those big chairs outside. I looked down in the dust and there was a copy of Olivier’s autobiography. This is approaching karma here. It took me three years to figure out how to structure it. But once I figured it out, I wrote it real fast, and I sent it to Steppenwolf.

I once met Vivien Leigh. That was quite a haunting meeting we had.

twi-ny: What were the circumstances?

ap: Well, it was toward the end of the year I was in Oh Dad, Poor Dad, and I had already decided to leave. But Jerry Robbins would not let me leave. He said, No, if you leave the show, the word will get out why, and you won’t ever act again, and I want you to act for the rest of your life.

twi-ny: He didn’t often say a lot of nice things to people.

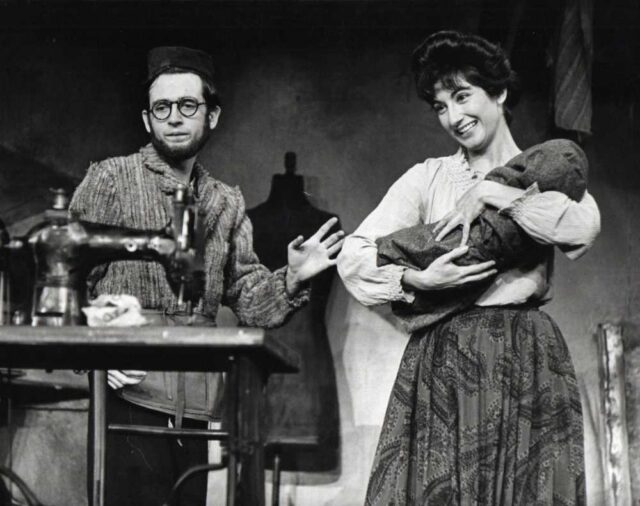

Austin Pendleton originated the role of the tailor Motel Kamzoil in Fiddler on the Roof

ap: No, and sometimes he didn’t say a lot of nice things to me. But he cast me again in Fiddler on the Roof, and then he cast me in two shows that he withdrew from before rehearsals began, a thing that he frequently did, and when he left them, I left them too. He cast me four times. He came to see almost everything that I acted in for years, and he would always comment, You’re hardly stuttering at all anymore. You’re not stuttering at all. I was reading his biography by Amanda Vaill, reading about his early years, and he stuttered.

twi-ny: Oh, isn’t that interesting. That must be part of why he wanted you to succeed.

ap: Yes, exactly. The psychology of stuttering is so interesting. As soon as Jerry found his capacities as a dancer and then almost immediately after that as a choreographer, it completely went away. They’re still trying to figure out the psychology of stuttering.

twi-ny: I mean, just think how a guy could actually deliver a State of the Union address, can make it an hour-plus on his feet giving a speech.

ap: Yes, Joe and I have a lot in common.

twi-ny: Here’s my last question.

ap: You can talk as long as you want.

twi-ny: Oh, well, okay, then I have a couple of other things that I will bring up. How do you imagine Orson, if he were alive, would react to your play?

ap: Well, I think the play treats him very sympathetically. I mean, who knows what Orson would think about it? I think he might like it. He was so impossible the two weeks [on Catch-22], but then, right at the end of the two weeks — among other things, by the way, he was incredibly superstitious. One of the superstitions is on a film, you don’t start a new scene on a Tuesday. There was a scene that Mike had to begin on a Tuesday; Orson spent the whole afternoon completely blowing his lines so none of the takes could be used. He was wildly superstitious.

But he came up to me at the end of the two weeks, as we were about to depart, and he was very kind, very, very nice.

twi-ny: Part of the inspiration in writing the play was that you felt bad about the snide remarks you had made about him on that press day.

ap: That’s right.

twi-ny: So you weren’t looking to take him down a notch.

ap: Not at all.

twi-ny: It wasn’t vindictive. It was really celebratory of him and what he had done, except for maybe blowing his lines on purpose and taking over for Mike Nichols.

ap: He wanted to have directed the film. He came out and said so.

twi-ny: The characters in Orson’s Shadow are well known, and most of them had been married multiple times and had had various affairs, including one going on during Rhinoceros. Meanwhile, you have been married to the same woman, Katina Cummings, since 1970. What’s the secret to being married for fifty-plus years in this business?

ap: The secret is about 89% of the time we get along fine, and the other 11% we fight.

twi-ny: It’s a good balance.

ap: Yeah, and that keeps the blood flowing.

twi-ny: That’s great. And I see that you now have the biggest smile you’ve had during this talk, when I mentioned your wife. So the two of you are still madly in love.

ap: Yeah, yeah, we get along fine. Her sister lives just a few blocks up the road, and I love her too.

twi-ny: Life is good.

ap: Our daughter is a surgeon, and her husband’s a doctor also. They have two little kids, each of whom has taken charge of the whole situation.

twi-ny: Going back to what Ethan Hawke said about you, I don’t think Marlon Brando ever had that.

ap: I’m not sure he ever wanted it.

[Mark Rifkin is a Brooklyn-born, Manhattan-based writer and editor; you can follow him on Substack here.]