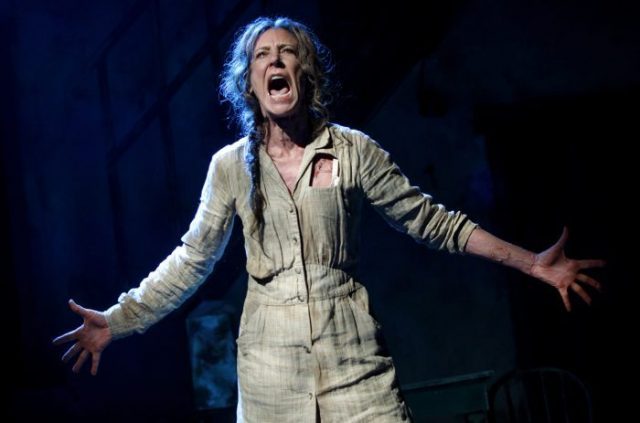

Hester Smith (Christine Lahti) cries out at her continuing misfortune in Signature revival of Suzan-Lori Parks play (photo © 2017 Joan Marcus)

The Pershing Square Signature Center

The Romulus Linney Courtyard Theatre

480 West 42nd St. between Tenth & Eleventh Aves.

Tuesday – Sunday through October 8, $30 ($85 after October 1)

212-244-7529

www. signaturetheatre.org

While canoeing about twenty years ago, Suzan-Lori Parks was randomly struck with the title of a play inspired by Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter: She wanted to write a show called Fucking A. It’s a great name for an ambitious work that turned out to be neither a reimagining of nor a response to the 1850 literary classic about adultery and punishment in 1642 Puritanical Boston but instead something wholly its own, with just a few key references to Hawthorne’s book. A fresh, stirring revival of that 2000 play opened last night as part of Parks’s Signature Theatre residency, running in tandem for the first time with its Hawthorne-related companion, 1999’s In the Blood, which together are known as the Red Letter Plays. Fucking A takes place in “a small town in a small country in the middle of nowhere,” where Hester Smith (Christine Lahti) works as an abortionist, an always-visible “A” branded into her skin. She is saving money so she can have a picnic with her son, Boy Smith, who has been in jail for thirty years for having stolen some meat from the very wealthy family he and his mother cleaned for. The rich girl who told on him is now the First Lady (Elizabeth Stanley), wife of the Mayor (Marc Kudisch). Furious that his spouse has been unable to give birth to his heir, the Mayor is having an affair with Canary Mary (Joaquina Kalukango), Hester’s best friend, who wants to marry the Mayor but in the meantime is more than willing to accept his money as payment for services rendered. Commenting on Canary Mary’s sexy yellow dress and high heels, Hester says, “It makes you look like a whore.” Canary responds, “I am a whore.” Hester counters, “Yr a kept woman,” to which Canary replies, “Im a whore. Yr an abortionist Im a whore.” Everyone in this unnamed place, in an unnamed time that could be the past, the present, or a postapocalyptic future, is just as direct, knowing exactly who they are and what they want out of this world, as indicated by the appellations Parks gives them, most of which describe their position and/or their inner nature. Hester is being courted by the kindhearted Butcher (Raphael Nash Thompson), who is not bothered by what she does for a living. (In a crafty touch, they wear matching bloodstained aprons.) Everyone is on edge when a convict, Monster (Brandon Victor Dixon), breaks out of prison and is on the loose, being tracked by a trio of Hunters (J. Cameron Barnett, Ben Horner, and Ruibo Qian) who can’t wait to capture and torture him, setting up a brutal conclusion.

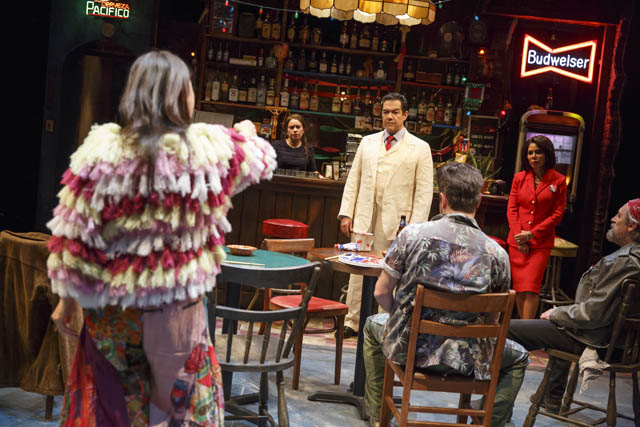

The First Lady (Elizabeth Stanley) slyly eyes her husband (Marc Kudisch) in Fucking A (photo © 2017 Joan Marcus)

In Fucking A, Parks, the first African American woman to win the Pulitzer Prize for Drama (in 2002 for Topdog / Underdog), has created an updated classical tragedy fraught with contemporary societal issues. Despite the characters’ descriptive names, they go beyond mere caricature as they deal with systemic misogyny, racism, class conflict, financial and education imbalance, fearmongering, legalized abortion, rape, and general injustice. Determined to get vengeance, Hester declares about the Mayor’s wife, “When she was a little Rich Girl she thought she owned the world. And anything she wanted she could buy. Sent my son away to prison with a flick of her little Rich Girl finger. She cant buy a son or a daughter now but I can buy mine. Im buying mine back.” Hester has been paying into the Freedom Fund for years in order to just visit her son, but the cost keeps going up as his sentence keeps getting longer; as the fund’s motto says, “Freedom Ain’t Free!” The actors, many of whom also play musical instruments in the balcony, occasionally turn to Brechtian song, both serious and funny, to further their characterization and the plot, something that Obie-winning director Jo Bonney (Lynn Nottage’s Meet Vera Stark, Parks’s When Father Comes Home from the Wars) works in seamlessly. The Hunters sing, “With jobs so scarce and times so hard / Some folks have turned to crime / The law locks all the bad ones up / They lock em up all the time / When law locks em up, they make a fuss / But when they escape, it’s good for us! / Cause we hunt.” Referring to his semen and the loyalty he so craves, the virile Mayor proudly belts out, “Marching and swimming / And marching and swimming / Saddle up! / Take aim! / Atten-tion! / At ease! / Charge! Charge! Charge! Charge!” And in a duet Hester and Canary explain, “Its not that we love / What we do / But we do it / We look at the day / We just gotta get through it. / We dig our ditch with no complaining / Work in hot sun, or even when its raining / And when the long day finally comes to an end / We’ll say: ‘Here is a woman / Who does all she can.’”

An escaped convict (Brandon Victor Dixon) rattles a close-knit community in one of Suzan-Lori Parks’s Red Letter Plays (photo © 2017 Joan Marcus)

Rachel Hauck’s ramshackle set usually serves as the room where Hester cleans up after performing abortions but is swiftly turned into a local pub, Butcher’s shop, a bench by the ocean, and the Mayor’s house, with a dark open doorway and stairs in the back that harken to something more outside. When talking about abortions, sex, and their vaginas, the women often speak in a different language called Talk, which is translated in surtitles; the only male who can understand even a few words and sentences of the women’s Talk is the sensitive and caring Butcher. Emilio Sosa’s costumes further define the characters while maintaining the mystery of time and place; Hester’s blood-soaked apron and the Scribe’s (Kudisch) outfit seem to fit in the Middle Ages, while the Mayor’s suit and the First Lady’s and Canary Mary’s clothing is decidedly modern. Oscar, Obie, and Emmy winner Lahti (Chicago Hope, Swing Shift) is transcendent as Hester, her every gesture signaling the utter desperation she feels, trapped by her “stinking weeping” brand. Thompson (Black Codes from the Underground, Pericles) is sweetly touching as Butcher, who delivers an extensive monologue on all of the crimes his daughter has committed, listing just about everything under the sun, including at least several sins that every member of the audience knows only too well, tacitly implicating each one of us in the proceedings. Three-time Tony nominee Kudisch (Hand to God, Assassins) deliciously chews up whatever is in his path as the Mayor and the drunken Scribe while also playing the bass guitar, and Stanley (On the Town, Company), in her daringly red dress, and Kalukango (The Color Purple, Our Lady of Kibeho), in her bold yellow attire, are excellent as two very different women who are essentially after the same thing. Parks, whose Signature residency began with The Death of the Last Black Man in the Whole Entire World AKA the Negro Book of the Dead and Venus and continues with In the Blood, which opens September 17, is fierce in her writing, which sparkles with overt and subtle dichotomies that bring it all together beautifully. Lastly, in a time when color-blind casting is all the rage, the ethnicity of the actor playing Hester has a critical impact on the play. In the 2003 production at the Public Theater, S. Epatha Merkerson was Hester (with Bobby Cannavale as the Mayor, Daphne Rubin-Vega as Canary Mary, and Peter Gerety as Butcher); the entire power dynamic shifts depending on Hester’s color (as well as that of other characters), a thought that can send even more shivers down your spine than you’re already experiencing watching this superb revival. We can think all we want that we don’t see color, but it’s another key part of what makes Fucking A fucking awesome.