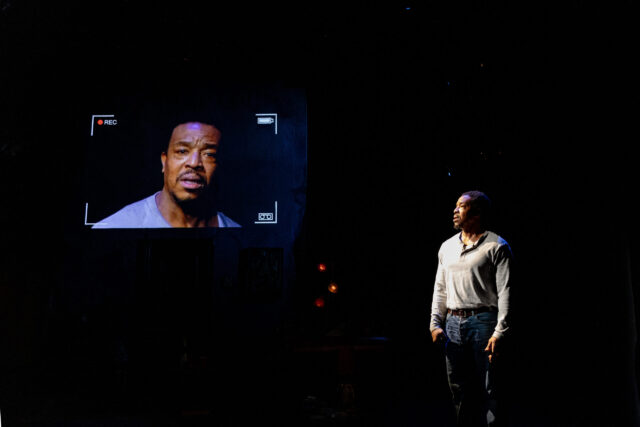

New play takes place at a grief counseling session (photo by Julieta Cervantes)

someone spectacular

The Pershing Square Signature Center

The Romulus Linney Courtyard Theatre

480 West 42nd St. between Tenth & Eleventh Aves.

Through September 7, $39 – $240

someonespectacularplay.com

Pardon me if I enter a theater and am instantly downtrodden upon seeing a bunch of folding chairs, a table with coffee and snacks, and characters slowly and quietly entering the room and taking their seat, apparently preparing to share.

In the past year, New York City been inundated with plays set at least partially in therapy sessions dealing with grief and trauma, both group and one-on-one. Immediately coming to mind are Emma Sheanshang’s The Fears, Those Guilty Creatures’ The Voices in Your Head, Ruby Thomas’s The Animal Kingdom, Marin Ireland’s Pre-Existing Condition, John J. Caswell Jr.’s Scene Partners, and Liza Birkenmeir’s Grief Hotel.

“This is a waste of time,” one character says near the beginning of Doménica Feraud’s someone spectacular.

“We’re not allowed to have fun?” another responds.

The ninety-minute play, continuing at the Pershing Square Signature Center’s Romulus Linney Courtyard Theatre through September 7, has plenty of laughs amid the darkness. It takes place in a cold office space under industrial lighting (designed by the collective dots) where a small group of people meet every Thursday night to talk about “someone spectacular” they’ve recently lost. Fifty-six-year-old Thom’s (Damian Young) wife died of cancer. Forty-seven-year-old Nelle (Alison Cimmet) feels lost since her sister passed. Twenty-six-year-old Julian (Shakur Tolliver) is having trouble dealing with the death of his beloved aunt. Twenty-two-year-old Jude (Delia Cunningham) is new to the group, having suffered a miscarriage. And fifty-one-year-old Evelyn (Gamze Ceylan) is there because she doesn’t understand why she is so sad at the loss of her mother, with whom she did not have a good relationship, while thirty-year-old Lily (Ana Cruz Kayne) is suicidal over her mother’s death, having seemingly lost the only person in the world who cared about her.

When group facilitator Beth is late, the six characters are not sure what to do, whether to wait for Beth to arrive, start the meeting without her, or go home.

“I’m sure she’ll be here soon,” Evelyn says.

“Beth wouldn’t abandon us,” Julian adds.

“People leave you halfway through the wood a lot more often than you think,” Lily asserts.

As time goes on and Beth doesn’t even check in via text, they vote to go on with the session, leading to the breaking of numerous rules as they evaluate and compare one another’s pain and priorities in both comic and mean-spirited ways. Thom is cool and calm but won’t stop taking business calls. Evelyn is caring and understanding. Lily is angry and selfish. Julian is relaxed and easygoing. Jude is sad and defensive. And Nelle is nasty and condescending.

They discuss pasta, Joe Rogan, vaping, shoes, banana bread, plants, and cults as they contemplate their personal situations and who should be the replacement Beth.

“Do you think Beth’s dead? I think Beth’s dead,” Lily declares.

“That would be kind of funny,” Julian says.

“How would that be funny?” Thom asks.

“I don’t know. We lost people we weren’t supposed to lose. I just think it would be funny if our grief counselor up and died on us,” Julian responds.

Nelle (Alison Cimmet) often finds herself in the middle in Doménica Feraud’s someone spectacular (photo by Julieta Cervantes)

The one-act play is adroitly directed by Tatiana Pandiani (Bodas; Field, Awakening), avoiding stasis and boredom as the characters’ movements, both subtle and overt, help define who they are, from Nelle’s quiet insistence of placing an empty chair next to her to Julian’s enjoyment of the banana bread and Lily’s disregard for what’s in her bag. Siena Zoë Allen’s naturalistic costumes further establish their identities, from Julian’s shorts and T-shirt to Evelyn’s high heels and Lily’s hoodie and sneakers.

Feraud’s (Rinse, Repeat) dialogue can be sharp and incisive but then go off on a tangent, like when the group engages in the adult game Fuck, Marry, Kill. There are also red herrings involving an occasional beeping and flickering lights. (The sound is by Mikaal Sulaiman, lighting by Oona Curley.)

The ensemble is compelling, led by Cimmet’s (Party Face, The Mystery of Edwin Drood) aggressive performance as the disagreeable Nelle, Ceylan’s (Noura; Field, Awakening) steadiness as the ever-practical Evelyn, and Young’s (Sacrilege, The Waiting Room) easygoing nature as the forward-thinking Thom, the only one ready to move on with his life.

Be sure to get there several minutes before curtain and pay attention to the set; as the audience enters, so do the actors, one at a time, getting coffee, checking their phones, or staring into space. It’s almost as if they could take a seat in the audience and we could settle onstage, but while we watch them, the actors never make eye contact with the audience until their bows at the end. No one goes through life without suffering some kind of loss, some kind of tragedy, and we all have unique ways to deal with it, rules be damned. No one wants to feel abandoned, and no one wants to be judged.

Yes, someone spectacular is yet another show about grief counseling, but it also accomplishes what theater does best, bringing us all together, encouraging us to look at our own choices while watching those of others.

[Mark Rifkin is a Brooklyn-born, Manhattan-based writer and editor; you can follow him on Substack here.]