Sil (Ellen Parker), Mac (Franchelle Stewart Dorn), Danny (Polly Draper), and Gabby (Kathryn Grody) celebrate forty years of friendship in 20th Century Blues (photo © Joan Marcus)

The Pershing Square Signature Center

The Alice Griffin Jewel Box Theatre

480 West 42nd St. between Tenth & Eleventh Aves.

Tuesday – Sunday through January 28, $79-$99

212-244-7529

20thcenturyblues.com

www.signaturetheatre.org

I spent much of the summer of 2014 serving on a jury for a murder trial, a case involving a drug-related shooting in Harlem. One of my fellow jurors was writer, director, and Emmy-nominated actress Polly Draper. Best known for her portrayal of Ellyn Warren on the groundbreaking drama thirtysomething, the Yale grad (both BAA and MFA) has also starred on and off Broadway (Closer, Brooklyn Boy); wrote and starred in The Tic Code, inspired by her husband, jazz musician Michael Wolff, who has Tourette’s syndrome; and wrote and directed The Naked Brothers Band television series and movie, starring their sons, Nat Wolff (The Fault in Our Stars, Buried Child) and Alex Wolff (In Treatment, All the Fine Boys). Draper, who has also won a Writers Guild Award, has been experiencing a career renaissance of late, portraying recurring characters on The Big C with Laura Linney, The Good Wife with Julianna Margulies, and Rhinebrook, as well as playing a key supporting role in the Kickstarter-funded indie hit Obvious Child.

She is now appearing off Broadway through January 28 at the Signature in 20th Century Blues, a bittersweet drama written by Susan Miller (My Left Breast, A Map of Doubt and Rescue) and directed by Emily Mann (Baby Doll, The How and the Why) about four sixtysomething women who have been getting together once a year ever since they met when they were all arrested at a political protest forty years earlier. Draper plays Danny, a divorced photographer and mother who has taken their picture every year. When Danny tells journalist Mac (Franchelle Stewart Dorn), veterinarian Gabby (Kathryn Grody), and real estate agent Sil (Ellen Parker) that she is having a solo show at MoMA and wants to include the forty years of photos, displaying them publicly for the first time, questions arise as the women look back at their past and consider their future. Danny is also contemplating taking care of her aging mother, Bess (Beth Dixon), in her apartment, which her friends do not think is the best idea. “She’s my mother,” Danny explains. “And, I don’t know how long I’ll get to be a daughter.” (That line rang extra true for me, as a half hour after I saw the play last week, my mother passed away in my sister’s Upper East Side apartment.)

A relaxed, easygoing woman with a broad sense of humor and a natural talent for leadership, Draper, like Danny, is passionate about everything she does. “When it comes to my art, I have very strong feelings,” she said when we met to talk shortly after the bizarre trial ended with a hung jury. And also like Danny, she is passionate about justice and freedom, as evidenced by her reactions to the trial in addition to her activism for numerous liberal causes. What follows are edited excerpts from our 2014 interview and a brand-new email exchange about 20th Century Blues, the legal system, working with family, and more.

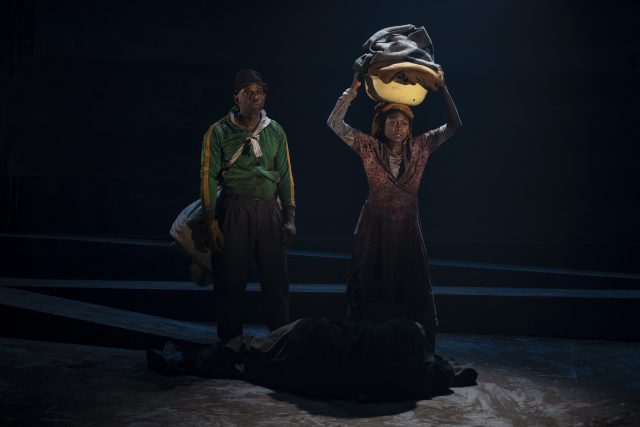

Danny (Polly Draper) cares for her aging mother (Beth Dixon) in new play by Susan Miller (photo © Joan Marcus)

twi-ny: I can’t believe it’s been three and a half years since we sat on that long, bizarre murder trial. What are your thoughts looking back at that summer in court? At the time you called it a musical comedy.

Polly Draper: I think about that experience so much!!! And did you hear that those guys got convicted finally? I guess the second jury didn’t have our crazy guy on it. But I doubt they had as much fun as we did! What a mind-blowing experience!!!

twi-ny: I know! What was your single favorite moment of the trial?

Polly Draper: Meeting you guys. Meeting all the fun people and going out to the Chinese restaurants. I had a lot of fun. The only thing that wasn’t fun was the deliberations because of the crazy person. But even the deliberations had their fun things, like every time he’d fall asleep or when he wasn’t there. All the characters . . . It was fascinating for me in every way.

twi-ny: If you knew then what you know now, would you put yourself through it again?

Polly Draper: Definitely! Absolutely! I know some of the people wouldn’t say that at all, but I would so do it. It’s one of the most fascinating things that happened in a long time to me.

twi-ny: You’re currently starring in Susan Miller’s 20th Century Blues at the Signature. What initially drew you to the play itself and your part specifically?

PD: First of all, I was drawn to the play because it dealt with friendships between women and also with issues common to women my age. Plays written on this subject matter are few and far between.

Secondly, I really related to the character I was playing and her struggle to realize her artistic vision, which in her case involved putting together a photography exhibit at MoMA. Having struggled with many of my own artistic endeavors, I could identify with the obstacles she faced.

I also intimately understand this character’s relationship with her mother, who is in the throes of dementia, because my own mother is suffering from Parkinson’s disease–related dementia.

twi-ny: I’m sorry to hear that. The play follows four women who have documented their friendship through forty years of photos. What’s your longest current friendship?

PD: I’ve known my oldest friend, Wende Lufkin, since we were eight years old and share all my childhood and teenage memories with her. We live on opposite sides of the country and rarely see each other but are inextricably bonded by our shared past.

The two old friends I see constantly and have been entwined in my life for the past forty years are writer Jenny Allen, who I met in college, and actress Brooke Adams, who I met doing a play when I first came to NYC. (The two of them were at opening night for this play, in fact, rendering it even more meaningful to me.)

twi-ny: Speaking of long friendships, it’s now been forty years since thirtysomething debuted. In June 2007, you reunited with the cast for a “Look Who’s Fifty” story, and this past September EW did a “Where Are They Now?” feature. It really was quite a group of creative people; all these years later, everyone is still very busy, with many of the actors becoming directors, including yourself. Why do you think that might be?

PD: When we were on thirtysomething, all the actors were encouraged to direct. Regrettably, I wasn’t interested in doing so at the time, but I think the fact that so many of my cast members did it demystified the process for me. We were also encouraged to volunteer ideas for scripts, which got me interested in the whole process of script writing. Some of my castmates, like Melanie Mayron and Peter Horton, had already been directors and writers before they got on the show.

Everyone in the cast was smart and ambitious. So . . . I’m guessing that accounts for all the many directing / writing / acting projects among us.

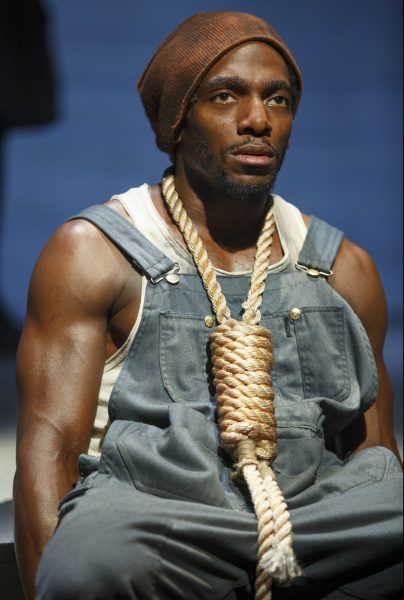

Emmy nominee and Writers Guild Award winner Polly Draper has a passion for art, social justice, and family (photo by Carol Rosegg)

twi-ny: You’ve directed your family in The Naked Brothers Band series and movie, wrote and starred in The Tic Code, which was inspired by your husband’s Tourette’s syndrome, directed one of your sons in a play written by your other son, and next up is Stella’s Last Weekend, which you wrote, directed, and star in with your sons. Why do you think working with your family has gone so well? Do things ever get especially difficult either on the set or back at home?

PD: My family is the most important thing to me, so it is not surprising that all of the work I have created involves them. And it doesn’t hurt that they happen to be extraordinarily gifted actors and musicians.

I was actually surprised by the lack of stress we had on the set of Stella’s Last Weekend. The last time I worked professionally with Nat and Alex was on The Naked Brothers Band when they were wild and crazy little boys, so it was a treat for me to work with them as wild and crazy adults.

Because we worked together before and because we all know each other so well, we not only trusted each other, we have a shorthand communicating with each other. This resulted in all of it feeling surprisingly effortless from beginning to end. Nat and Alex both had great ideas for their characters and great improvisations they did in the scenes. They also kept everyone on the set in constant hysterical laughter with their brother antics.

I think the movie reflects the joy we all had making it. I am really proud of it and I can’t wait until it comes out so people can see it. The screenings we have had of it so far have been phenomenally successful.

And Michael, who also did the score for The Tic Code and The Naked Brothers Band, did a killer score for this one too.

twi-ny: Would you say that the camaraderie that you helped foster in the jurors room during the trial compares to that on a film set?

PD: That’s what my husband said. He said, “This is just typical of you. You always wind up hanging out with the people you’re doing a project with, and this is your new project.”

twi-ny: You move smoothly between film, television, and theater, from Obvious Child, The Good Wife, and Golden Boy to Closer, Rhinebrook, and now 20th Century Blues. Do you have a particular preference as an actor for one medium over another?

PD: I think I just like doing work I’m proud of. I like working on interesting projects no matter what medium they’re in.

There are advantages to the control you have and the instant audience feedback of acting onstage, but there is something magical about the intimacy of acting on film as well.

I love to write scripts because I can play every role in my head.

I love to direct because it is thrilling to create the real-life version of what used to be just my fantasy.

It is also beyond exciting to watch what each actor brings to my words.

I also love the process of editing because it is so much fun to give shape to the movie and fix mistakes and choose music and find meanings in all of it that I never saw before.

So basically, I love every part of the process of acting, writing, and directing except the actual business part. That part I hate and fear. Unfortunately, it is one of the most important parts!

twi-ny: Getting back to the play, what gave you the blues in the twentieth century? And what about now, in the twenty-first century?

PD: Oy vey. I guess the simple answer would be to say that the blues I had in the twentieth century were more personal and involved growing up, and the blues I have in the twenty-first century are more global and involve fear for all of mankind.

When you and I served on that jury almost four years ago and Obama was still president, I don’t think either of us could have guessed the seismic shifts that have happened this year. The list of things that give me the blues now have to do mostly with our president and the flame he fans of lies and hatred and backward thinking, but he seems to be just a by-product of a frightening trend worldwide.

My blues in this century are every thinking person’s blues: They concern the environment, the spread of misinformation, North Korea, Putin, guns, nuclear holocausts, sexual predators, prescription drugs, women’s rights, civil rights, immigrants’ rights, terrorists, the Koch brothers and where they put their dark money, Steve Bannon and his scary white supremacy fans, cyberwarfare, Republican congressmen, our judicial system, and any old men with weird orange hair.