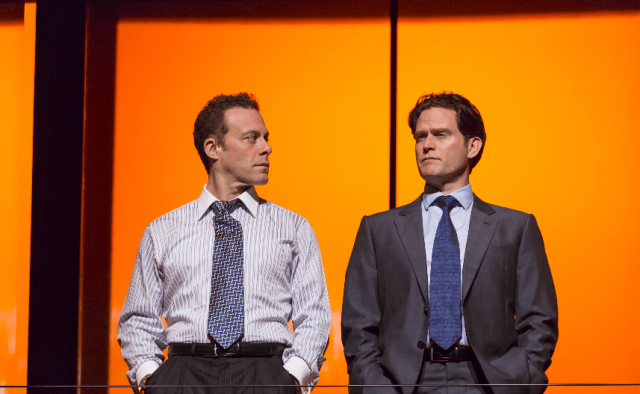

Red Bull and Fiasco join forces for delightful revival of The Knight of the Burning Pestle (photo by Carol Rosegg)

THE KNIGHT OF THE BURNING PESTLE

Lucille Lortel Theatre

121 Christopher St. between Bleecker & Hudson Sts.

Monday – Saturday through May 13, $77-$112

212-352-3101

www.redbulltheater.com

www.fiascotheater.com

After seeing the wonderful revival of Francis Beaumont’s 1607 comedy The Knight of the Burning Pestle, a collaboration between Red Bull and Fiasco that opened last week at the Lucille Lortel Theatre, I rushed home to read up on the Elizabethan pastiche. Surely these two inventive and consistently reliable New York–based companies had made significant changes to the plot, which centers on what I imagined was a twenty-first-century twist when it came to breaking the fourth wall. But to my delightful surprise, directors Noah Brody and Emily Young have remained faithful to the original story, though adding plenty of playful touches along the way.

The festivities kick off as an ensemble announces that it is about to present a show called The London Merchant when a grocer named George (Darius Pierce) jumps out of the audience and onto the stage, demanding that the troupe perform a different play. “Down with your title!” he proclaims. Believing they are elitists who “sneer at citizens,” George would prefer a play about the common man — say, a grocer — with a title like The Legend of Lord Wittington and His Exemplary Cat or The Story of Queen Elenor with the Rearing of London Bridge from a Tax on Woolsacks.

He is soon joined by his wife, Nell (Jessie Austrian), and they convince the actors to add George’s apprentice, Rafe (Paco Tolson), to the cast, as a stately, heroic grocer they christen the Knight of the Burning Pestle. After initial hesitation, the ensemble decides to proceed with the show, with Rafe’s presence providing the opportunity for everyone to improvise. George and Nell, meanwhile, sit in chairs at stage left, critiquing everything and interrupting whenever they don’t like what’s happening — usually involving Rafe’s not getting enough to do.

In the central narrative, apprentice Jasper Merrythought (Devin E. Haqq), who serves the wealthy Venturewell (Tina Chilip), is in love with his master’s daughter, Luce (Teresa Avia Lim). But Venturewell has decided to marry her off to fashionable gentleman and dullard Humphrey (Paul L. Coffey). “You know my rival?” Jasper asks Luce, who replies, “Yes, and love him dearly, even as I love an ague or foul weather; I prithee, Jasper, fear him not.”

Venturewell (Tina Chilip) tries to force Luce (Teresa Avia Lim) to marry Humphrey (Paul L. Coffey) in 1607 comedy by Francis Beaumont (photo by Carol Rosegg)

When Venturewell tells Humphrey, “Come, I know you have language good enough to win a wench,” Nell cries out, “A whoreson mother! She’s been a panderer in ’er days, I warrant her.” George holds his wife back, saying, “Chicken, I pray thee heartily, contain thyself.” He then turns to the actors and says, “You may proceed.” Such interruptions continue throughout the play, becoming more and more disruptive.

Meanwhile, Jasper’s parents, Charles (Ben Steinfeld) and Mistress Merrythought (Tatiana Wechsler), have apparently fallen out of love. She is a determined woman who will not give her blessing to her eldest son, whom she considers a “waste-thrift,” instead promising her inheritance to her other child, Michael (Royer Bockus). The unemployed Charles has spent nearly all his money on fine food and drink but still finds joy in life, particularly when it comes to singing, much to his wife’s chagrin. She commands that he is responsible for Jasper’s future, expecting them both to fail miserably.

Among the other characters are Rafe’s apprentice, Tim (Steinfeld), who accompanies the knight on his journey of protecting fair ladies and distressed damsels; the squire Tapster (Paul L. Coffey), who runs the Bell End Inn with a threatening host (Chilip); the evil giant Barbaroso (Haqq); the lusty princess of Cracovia (Austrian); and Little George (Bockus), Rafe’s faithful horse.

The Knight of the Burning Pestle is a great choice for Red Bull and Fiasco to team up on. The latter specializes in Jacobean dramas and farces (Ben Jonson’s Volpone, John Ford’s ’Tis Pity She’s a Whore, Richard Brinsley Sheridan’s The School for Scandal) as well as modern takes on Shakespeare (Coriolanus, Erica Schmidt’s Mac Beth), while Fiasco alternates among Stephen Sondheim (Into the Woods, Merrily We Roll Along), the Bard (Two Gentlemen of Verona, Twelfth Night, Cymbeline), and Molière (The Imaginary Invalid).

Royer Bockus, Ben Steinfeld, Paco Tolson, and Tatiana Wechsler are part of terrific ensemble in The Knight of the Burning Pestle (photo by Carol Rosegg)

Their sensibilities mesh in organic ways in this splendid interpretation of Beaumont’s rarely performed play. Christopher Swader and Justin Swader’s set features a wooden floor and back wall, the latter with surprise openings. Two painted backdrops move the action to an inn and the forest, and a rolling door serves as the entrance to the Merrythought home. There are chairs scattered on each side, where the actors sit when they’re not part of the scene, some occasionally playing instruments, a hallmark of Fiasco productions. Some musical interludes work better than others; a group singalong on the old-time ballad “De Derry Down” is engaging, and a jolly version of Cole Porter’s “Let’s Misbehave” is delightfully frisky, but a rewritten take on Bobby McFerrin’s “Don’t Worry Be Happy” and a too-long solo by Steinfeld in which he makes sounds with his mouth and by striking parts of his body feel out of place.

Yvonne Miranda’s costumes range from the relatively contemporary to seventeenth-century traditional to theatrical makeshift, as when Rafe dons a metal colander for a helmet and uses a metal trashcan top as a shield. (The funny props are by Samantha Shoffner.) Reza Bahjat’s lighting includes nearly two dozen chandeliers and fixtures that extend over the audience, as if we’re part of the production — and we are, represented by George and Nell onstage.

The couple’s interventions are a mixture of purposely awkward and fresh, given the recent spate of shows having to stop or be delayed because of audience members yelling at actors, singing along too loud (contrary to theater instructions), or crawling onto the set to plug their phone into a fake outlet. When George gives the troupe two shillings in order to have specific music, it evokes a producer making an unreasonable demand, then watching closely to ensure it is done.

Brody and Young (you can watch an online RemarkaBULL Podversation with them here) have also performed in many of Fiasco’s productions; as directors, they get the best out of their talented cast, giving them a freedom that they gleefully embrace. Pierce chews up the scenery as the annoying George, Tolson excels as the stalwart Rafe, and Bockus brings the house down as Rafe’s horse.

Beaumont, who died in 1616 around the age of thirty-two, wrote only one other play by himself, The Masque of the Inner Temple and Gray’s Inn, while collaborating with John Fletcher on thirteen works, including The Woman Hater, A King and No King, and Philaster, or Love Lies a-Bleeding. I imagine he would be quite satisfied with Red Bull and Fiasco’s collaboration on The Knight of the Burning Pestle.