The divine Sarah Lucas rules over first American survey of her work at New Museum (photo by twi-ny/mdr)

New Museum

235 Bowery at Prince St.

Tuesday through Sunday through January 20, $12-$18

212-219-1222

www.newmuseum.org

I fondly recall being blown away in 2004 by “In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida: Angus Fairhurst, Damien Hirst & Sarah Lucas” at the Tate Britain, a terrific survey of three key Young British Artists who began making their mark in the late 1980s. I had previously been introduced to their work, and that of many other YBAs, in the Brooklyn Museum’s 1999 “Sensation: Young British Artists from the Saatchi Collection,” which became (in)famous when New York City mayor Rudy Giuliani threatened to close it, offended because Chris Ofili’s “Holy Virgin Mary” contained elephant dung. Giuliani is also unlikely to be a fan of “Sarah Lucas: Au Naturel,” the New Museum’s revelatory first American retrospective of the work of the London-born artist who boldly tells it like it is through photography, sculpture, video, collage, and installation.

The show at the New Museum, on view through January 20, highlights Lucas’s DIY aesthetic, her sly sense of humor, and her innate instincts to take on the status quo — particularly the patriarchy, traditional notions of domesticity, and misogyny — repurposing such found materials as furniture, cigarettes, tabloid articles, clothing, and cars along with numerous photos of herself, always shot by someone else, usually her partner at the time. But despite the apparent socioeconomic observations and art-historical references in her work, she is not merely trying to score political or artistic points as some kind of artivist. “I don’t think I make things for a specific type of public,” she tells New Museum artistic director Massimiliano Gioni in the catalog interview “It’s Raining Stones.” She continues, “I like to be as broad as possible. I’m not anti-intellectual or anything; I just think things can operate on different levels. I want to make works that anybody can relate to, not only the people from the art world, but also the ordinary man or woman on the street, from the particular class I came from.” Lucas left home at sixteen, spent time as a squatter, and eventually went to art school, but not as fulfillment of some lifelong bourgeois dream. Spread across three floors and the lobby, the retrospective celebrates her uniquely rowdy oeuvre, which can be as poignant and powerful as it is hysterical and in-your-face.

Sarah Lucas’s “Bunny Gets Snookered” has been reimagined for New Museum retrospective (photo by twi-ny/mdr)

Facing the elevator on the fourth floor is “Divine,” a giant photograph, turned into wallpaper, of a tough-looking Lucas wearing boots, jeans, a T-shirt, and leather jacket, sitting on steps that seem to come from nowhere, her legs spread-eagled. She is staring down at us, asserting her laid-back authority. On the adjoining wall to her left is “Christ You Know It Ain’t Easy,” a large depiction of Jesus, covered neatly in cigarettes, on a red-painted cross; to Lucas’s right is “Chicken Knickers,” a photograph of the artist from above her knees to below her chest, wearing a raw chicken over her underwear. On the floor are “This Jaguar’s Going to Heaven,” a burned car sliced in two, and “Priapos” (the God of Fertility) and “Eros” (the God of Love), a pair of huge concrete phalluses balancing on crushed cars. Lucas is joyfully equating sex and mortality, specifically male death, since the Jaguar can be considered a prestige purchase of wealthy men, while also aligning the artist as a godlike figure. But she brings it all back down to earth in a far corner, where her deliciously wicked Sausage Film shows her carefully slicing and eating a sausage served to her by her partner at the time, artist Gary Hume. Like her photo on the second floor, “Eating a Banana,” in which she is doing just that, Lucas has tons of fun deconstructing male signifiers while taking possession of the gaze, the artist knowingly looking directly at the viewer.

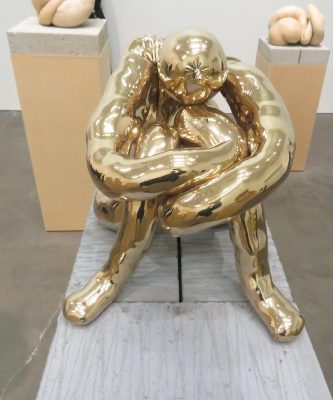

Sarah Lucas’s “NUDS” sculptures each gets its own pedestal (photo by twi-ny/mdr)

On the third floor, “One Thousand Eggs: For Women” is a long wall onto which, last September 13, a select group of women threw eggs, taking back their reproductive rights and control of their bodies. In the same room is a collection of Lucas’s “NUDS” sculptures, twisted, sometimes erotic shapes made either of tights, fluff, and wire or bronze on pedestals. “They happened very naturally, all different,” Lucas explains on the label about making them with her current boyfriend, Julian Simmons. “Slightly lewd in their nakedness. We named them ‘cuddle friends,’ after ourselves. Something about their babylike quality got me thinking about my relationship with my mum. That’s where ‘nuds’ came from. She called being naked ‘in the nuddy.’ She also called sadists ‘saddists.’ Not sure about the spelling, but ‘sad’ is the important bit. True, I think.”

In another room on the third floor, painted yellow, is a series of plaster sculptures of the bottom half of women’s bodies sitting on a chair, lying on a table, or kneeling over a toilet, a cigarette placed in a key part, with such names as “Yoko,” “Michele,” and “Sadie.” A black bronze feline, “Tit-Cat Up,” stands atop “Washing Machine Fried Egg (Electrolux),” a washing machine painted so its front looks like an egg yolk. And in the video Egg Massage, Lucas cracks eggs over Simmons’s naked body and rubs them into him, emphasizing man’s inability to conceive. She doesn’t necessarily set out to be so direct. In a wall label, Lucas explains, “It’s happened time and time again that some random spur-of-the-moment idea or juxtaposition has proved more fruitful than laborious projects I may have been working on — although it has to be said that these spontaneous notions could have been a reaction to, and relief from, the labor or high-mindedness I was engaged in. Conclusion: earnestness and hard work are to be regarded with suspicion.”

Toilets and other domestic items are central to Sarah Lucas’s oeuvre (photo by twi-ny/mdr)

The second floor is chock full of objects that are as engaging as they are unsubtle. “The Old Couple” consists of two wooden chairs, one with an erect phallus on it, the other false teeth. The titular piece, “Au Naturel,” is a cruddy mattress with melons, oranges, a cucumber, and a bucket on it, forming male and female sexual organs. In the R-print “Got a Salmon on #3,” Lucas is photographed with a huge salmon over her left shoulder, not about to swim upstream to spawn. (Lucas does not have children.) Lucas created “Beyond the Pleasure Principle” for the Freud Museum, using a mattress, a hanger, a concrete coffin, lightbulbs, a bucket, and a neon tube, offering a psychiatric look at sex and death. There are also skulls; phalluses made out of cigarettes and beer cans; and several toilets and photos of toilets, inside of one featuring the question “Is suicide genetic?” The centerpiece is “Bunny Gets Snookered,” a collection of eight of her soft bunny sculptures on chairs on and around a pool table, each bunny — a twist on the Playboy bunny? — the color of one of the snooker balls, playing off the double meaning of “getting snookered” in regard here to a predominantly male sport.

In her exhibition catalog essay “No Excuses,” writer and scholar Maggie Nelson notes, “I so value this New Museum retrospective, as it sidesteps the narrative of the mellowing of an angry, feral soul — that ‘calming down’ many inexplicably wish on our most crackling messengers — and instead allows us the time and space to look at the expanse of what Lucas has been doing from the start: making objects that ‘look fucking good’ out of a shape-shifting devotion to questions of anatomy, presence, ambivalence, rudeness, and humor.” I so value this retrospective as well, a seriocomic exploration of the gender and power dynamic, objectification, and traditional representation by an artist who is finally getting her due here in America.