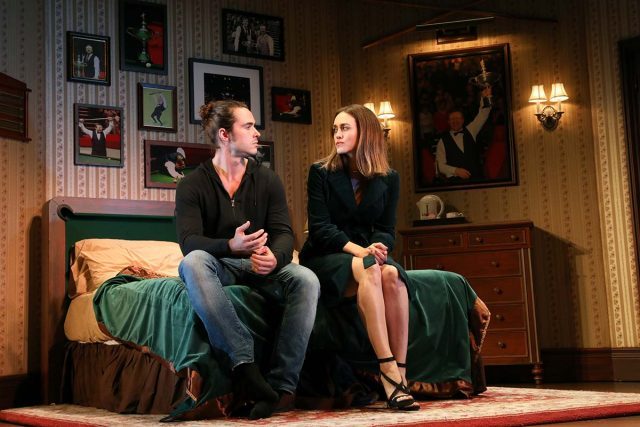

Pharus Jonathan Young (Jeremy Pope) pursues his singing dreams in Choir Boy (photo © Matthew Murphy, 2018)

Manhattan Theatre Club at the Samuel J. Friedman Theatre

261 West 47th St. between Broadway & Eighth Aves.

Tuesday – Sunday through February 24, $79-$169

choirboybroadway.com

www.manhattantheatreclub.com

Oscar-winning screenwriter Tarell Alvin McCraney’s Broadway debut, Choir Boy, offers a new twist on a classic dramatic trope: life at an all-male boarding school. But Charles R. Drew Prep School is not quite like the schools depicted in such well-regarded films as Rushmore, Dead Poets Society, Tom Brown’s School Days, Heaven Help Us, or If… The students and the teachers at Drew are all men of color. “My daddy say they used to let you get away with a lil bit because they know how hard it is to be a black man out there,” student Bobby Marrow (J. Quinton Johnson) tells fellow student David Heard (Caleb Eberhardt). “Now, everything got to be watched, gotta be careful, gotta be cordial. Don’t say nothing, don’t say that word, don’t look like that, this shit Pandemic.” Bobby, whose uncle is Headmaster Marrow (Chuck Cooper), is one of several young men in the school’s prestigious choir, along with Pharus Jonathan Young (Jeremy Pope), Junior Davis (Nicholas L. Ashe), Anthony Justin “AJ” James (John Clay III), and David. The show opens with Pharus singing the school song, a much-coveted opportunity, but he takes an unfortunate pause when he is secretly harassed by Bobby, who questions Pharus’s sexual orientation. Afterward, in explaining why he stopped but without snitching on Bobby, Pharus asks the headmaster, “Would you rather be feared or respected?” which becomes an underlying theme of the play as the boys deal with issues of race, gender, homophobia, family, class, and education.

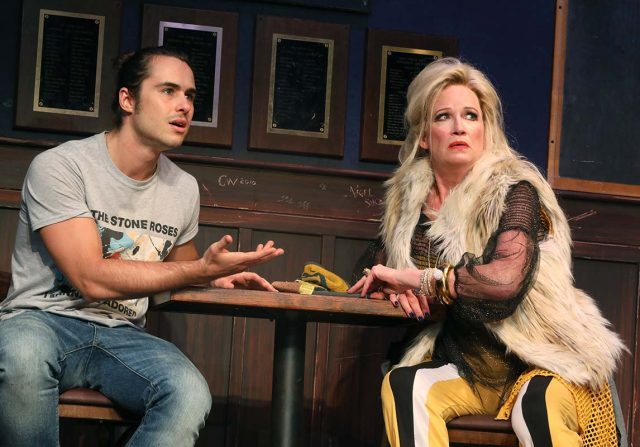

Bobby Marrow (J. Quinton Johnson) and Pharus Jonathan Young (Jeremy Pope) are at odds in boarding-school drama (photo © Matthew Murphy, 2018)

The play suffers dramatically upon the arrival of Mr. Pendleton, a former teacher at the school who has been brought back by the headmaster for inexplicable reasons, unless it is merely to force racial conflict, as Pendleton is white and, oddly, played by the ubiquitous Austin Pendleton, blurring the line between theater and real life in an obtrusive way. The scenes with Mr. Pendleton, who uses racist cracks to supposedly educate the kids, bring the show to a screeching halt and are best forgotten as the story proceeds. Fortunately, there is much to enjoy in the rest of the Manhattan Theater Club production, which has been extended at the Samuel J. Friedman Theatre through February 24.

Pope (Ain’t Too Proud, Invisible Thread) makes a dazzling Broadway debut as Pharus, a proud, flawed, young gay man who refuses to muzzle himself while often disregarding the feelings of others; it’s an electrifying performance of a role given complex subtleties by McCraney, who cowrote the Oscar-winning Moonlight with Barry Jenkins. The supporting cast portraying the other teens are terrific as well, including Clay III (Encores’ Grand Hotel) as AJ, Pharus’s roommate, who is sensitive to his friend’s situation; Johnson (Hamilton) as the troubled Bobby, who is dealing with his mother’s death; Eberhardt (Is God Is) as David, who is hiding his own secrets; and Ashe (Kill Floor) as Junior, a follower who makes questionable decisions. They might have their share of disagreements, but when they sing such spirituals as “Keep Your Eyes on the Prize” and “Rockin in Jerusalem” they show just what they can accomplish together. (Alas, “There’s a Rainbow ’round My Shoulder” feels a bit too obvious and heavy-handed.) Tony winner Cooper (The Life) is splendidly august as the headmaster, who only gets involved when truly necessary, understanding that the students grow when they figure things out for themselves, even if that’s sometimes painful. Thoughtfully directed by Trip Cullman (Lobby Hero, Six Degrees of Separation), Choir Boy is ultimately about tolerance, about the basic human dignity everyone deserves, while for the most part steering clear of grand statements and politically correct sentimentality.