The executive committee at Eureka Day School has its work cut out for it (photo by Jeremy Daniel)

EUREKA DAY

Samuel J. Friedman Theatre

261 West Forty-Seventh St. between Broadway & Eighth Ave.

Tuesday – Sunday through February 16, $48-$321

www.manhattantheatreclub.com

Jonathan Spector’s Eureka Day is the funniest play of the year.

Five years ago, I called Colt Coeur’s East Coast premiere of Eureka Day at walkerspace an “uproarious satire.” It’s even better in the Broadway debut of the Manhattan Theatre Club production at the Samuel J. Friedman, succeeding where a similarly themed show, Larissa FastHorse’s The Thanksgiving Play, about a woke quartet of grown-ups trying to put on an acceptable, PC holiday show for young schoolchildren, failed. The fall 2018 iteration of The Thanksgiving Play at Playwrights Horizons was fresh and original and utterly hilarious; its 2023 Broadway version was stale and outdated, like dried-out leftovers.

That doesn’t happen with Eureka Day, which strikes gold for the second time.

The story takes place in the fall of 2018 in the library of the Eureka Day School in Berkeley, California. The executive committee is meeting, and the opening dialogue sets the stage for what’s to come.

Meiko: Personally no / I don’t find it offensive / the term itself is not offensive.

Eli: It’s descriptive.

Suzanne: I think she’s saying / I’m not putting words in your mouth / she’s saying it’s not offensive / but when you contextualize it in that way. . . .

Meiko: I find / the best way not to put words in someone’s mouth? / is not to put words in their mouth.

Don: Okay okay.

Suzanne: Sorry sorry.

Meiko: It’s fine / what I meant was / that we’d want to make it absolutely clear that it’s optional / that it’s not / Either / Or.

Suzanne: Right / and also / that the inclusion of the term on this list at all is / I think / inappropriate? / and that some people may / With Good Reason / find its inclusion offensive.

Eli: No no yeah / I just wonder though / by leaving it off / is it possible some people would find its absence offensive?

Don: You’re concerned / that it could be a sort of / erasure / of people’s experience?

Eli: Right / if our Core Operating Principle here is that everyone should / Feel Seen / by this community.

Suzanne: There’s no benefit in Feeling Seen if you’re simultaneously Being Othered / right?

Meiko: Well / no yeah.

Don: Carina, did you want to / do you want to / offer anything?

Carina: Oh, I / I’m happy to defer / I don’t know that I’ve really formed a strong [opinion.]

Don: That’s perfectly all right / even just your gut instinct is [welcomed] / this is an Open Room / we welcome your unique perspective.

The discussion is about what to include in the school’s online dropdown menu where parents are supposed to click off their kid’s race/ethnicity/heritage, but it could deal with so many other subjects that are part of the committee’s efforts to be as inclusive as possible in any and all situations.

“Sounds like there’s a lot to unpack here,” Don says, but there’s a lot to unpack everywhere in this outrageously hilarious satire.

The white, childless Don (Bill Irwin) is the head of the committee and prefers not to take sides, ending each meeting with a quote from the thirteenth-century Sufi poet Rumi. The well-off, white Suzanne (Jessica Hecht) is a longtime board member who has put each of her six children through Eureka Day and regularly supplies the library with books. The white, Jewish Eli (Thomas Middleditch) is a wealthy tech bro with an open marriage and one son in the school. He is secretly dating the half-Japanese Meiko (Chelsea Yakura-Kurtz), who has a daughter in the school and spends much of her time knitting rather than actively participating in the committee’s proceedings. And the biracial Carina (Amber Gray) is filling the spot saved for the new member, hesitant to share her views until she can’t stop herself as it all becomes ridiculously absurd.

When a student contracts the mumps and the health department sends an official notice explaining that nonvaccinated children will be barred from attending school until they get their shot, the committee calls for a hybrid Community Activated Conversation, with parents commenting from home on the chat, which delves into vaccination efficacy, conspiracy theories, personal and public responsibility, and plenty of vicious name-calling.

Christian Burns: Wait. HALF the school is antivaxxers? Seriously????

Sandra Blaise: “Anti-vaxxer” is not really a term I’m comfortable with. It’s actually something said out of IGNORANCE.

Karen Sapp: Exactly! Protect your children by EDUCATING YOURSELVES.

Tyler Coppins: OR, Protect your children by VACCINATING THEM.

Courtney Riley: Wait what???? Why should we be forced to keep our kids home because you CHOOSE to endanger yours?

Doug Wong: Okay here’s another idea: what if we made the quarantine days OPTIONAL.

Orson Mankel: Doug, that’s idiotic. If the “problem” is that we won’t have enough kids in class, why make the problem worse???

Christian Burns: TRUE FACTS: Moonlanding wasn’t faked. 9/11 wasn’t an inside job. Global Warming is real. Vaccines Don’t Cause Autism.

Karen Stacin: Mock all you want, but I saw so many bad things as a nurse. That’s why I decided I would NEVER subject my children to Western Medicine of any kind.

Christian Burns: Remember that time I got crippled from polio? Oh, no, wait. I didn’t. Cause I got FUCKING VACCINATED.

Things only devolve from there in side-splitting ways that are even funnier — and more frightening — now that President-elect Donald Trump has nominated the controversial Robert F. Kennedy Jr. to run the Department of Health and Human Services.

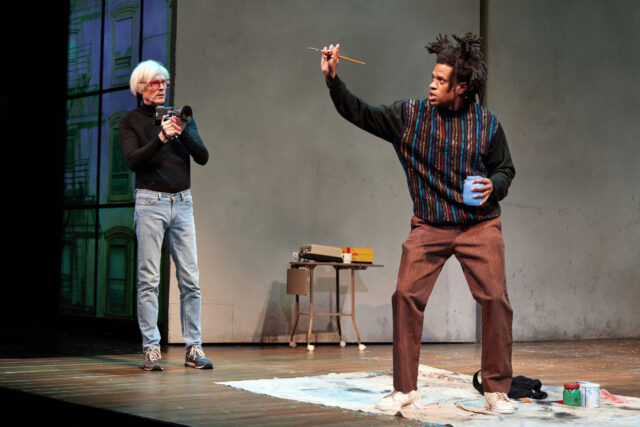

Community Activated Conversation at Eureka Day goes terribly wrong in hilarious Broadway play (photo by Jeremy Daniel)

Ancient Greek polymath Archimedes is often credited with coining the exclamation Eureka! upon discovering what became known as the Archimedes Principle, a scientific theory about buoyancy. So it makes sense that Spector has named the woke school in question Eureka Day. Todd Rosenthal’s set features blue chairs, red, orange, and yellow trapezoid tables that are rearranged into geometric shapes, posters of Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Albert Einstein, Maya Angelou, Sandra Day O’Connor, and Michelle Obama, and a sign that reads “Social Justice” under a placard that proclaims, “Berkeley Stands United Against Hate.” Clint Ramos’s naturalistic suburban costumes are highlighted by the long, fussy frocks worn by Suzanne.

Tony winner Anna D. Shapiro (August: Osage County, This Is Our Youth) directs with a sweet glee, while sound designers Rob Milburn and Michael Bodeen know just when the laughs are coming, particularly during the Community Activated Conversation, when David Bengali’s projections take over and the characters’ discussion fades into the background.

The ensemble is outstanding: Tony nominee Gray (Natasha, Pierre, and the Great Comet of 1812, Hadestown) is cool and collected as the determined Carina, who can’t believe what the board is doing; two-time Tony nominee Hecht (Summer, 1976, Fiddler on the Roof) is delightful as the nervous, jittery Suzanne, punctuating her dialogue with wonderful sighs and grunts; Tony winner Irwin (Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, On Beckett) is tender as the mild-mannered, oblivious Don; Emmy nominee Middleditch (Silicon Valley) adds humanity to the selfish Eli; and Chelsea Yakura-Kurtz (How the Light Gets In, Unrivaled) beautifully captures Meiko’s evolving value system as she reconsiders being part of the team.

As funny as Eureka Day is, it tackles some hard-hitting subjects, from race and income inequality to religion and health care; the executive committee is so wrapped up in DEI that they miss what is right in front of them, stirring up more trouble with their inability to follow old-fashioned rules and face the truth of what is really happening in their school, to the students.

At one point, the other members of the committee explain to Carina how there was controversy over a recent eighth-grade production of Peter Pan. “I don’t know what they were thinking,” Suzanne recalls. “We came to what I thought was a very [good agreement] / we set the production in Outer Space / and that really solved the [problem],” Don says. “So then all the kids got to fly,” Eli adds, as if that were the only solution, while Carina can barely accept what she has gotten herself into.

Fortunately, Eureka Day does not have to worry about any such controversies, as it gets it all right, flying high from start to finish.

[Mark Rifkin is a Brooklyn-born, Manhattan-based writer and editor; you can follow him on Substack here.]