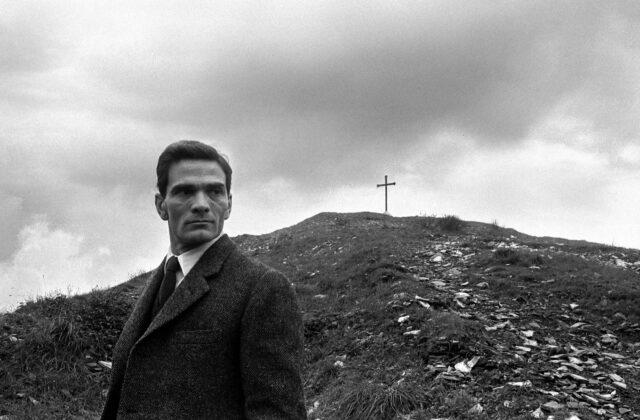

Franco Citti stars as the title character in Pier Paolo Pasolin’s directorial debut, Accatone

ACCATTONE (THE SCROUNGER) (Pier Paolo Pasolini, 1961)

Quad Cinema

34 West 13th St. between Fifth & Sixth Aves.

Sunday, November 26, 5:50

Series runs November 22-30

212-255-2243

quadcinema.com

After collaborating on a number of works by such auteurs as Mauro Bolognini and Federico Fellini, poet and novelist Pier Paolo Pasolini made his directorial debut in 1961 with the gritty, not-quite-neo-realist Accattone (“scrounger” or “beggar”). Somewhat related to his books Ragazzi di vita and Una vita violenta, the film is set in the Roman borgate, where brash young Vittorio “Accattone” Cataldi (Franco Citti) survives by taking crazy bets — like swimming across a river known for swallowing up people’s lives — and working as a pimp. After a group of local men beat up his main money maker (Silvana Corsini), he meets the more naive Stella (Franca Pasut), whom he starts dating with an eye toward perhaps converting into a prostitute as well. Meanwhile, he tries to establish a relationship with his son, but his estranged wife and her family want nothing to do with him. Filmed in black-and-white by master cinematographer Tonino Delli Colli, Accattone is highlighted by a series of memorable shots, from Accattone’s gorgeous dive from a bridge to a close-up of his face covered in sand, many of which were inspired by Baroque art and set to music by Bach. Written with Sergio Citti and featuring an assistant director named Bernardo Bertolucci — whose father was a friend of Pasolini’s — the story delves into the dire poverty in the slums of Rome, made all the more real by Pasolini’s use of both professional and nonprofessional actors. “Because he did not have much knowledge of film-making, he invented cinema. It was as though I had the privilege of assisting, of witnessing the invention of cinema by Pasolini,” Bertolucci later said of his experience. Accattone is screening November 26 as part of the Quad series “Pictures from the Revolution: Bertolucci’s Italian Period,” which runs November 24-30 and includes such other films that Bertolucci worked on, either as writer or director or in another capacity, as The Grim Reaper, Luna, Partner, 1900, the omnibus Love and Anger, and Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in the West.

After collaborating on a number of works by such auteurs as Mauro Bolognini and Federico Fellini, poet and novelist Pier Paolo Pasolini made his directorial debut in 1961 with the gritty, not-quite-neo-realist Accattone (“scrounger” or “beggar”). Somewhat related to his books Ragazzi di vita and Una vita violenta, the film is set in the Roman borgate, where brash young Vittorio “Accattone” Cataldi (Franco Citti) survives by taking crazy bets — like swimming across a river known for swallowing up people’s lives — and working as a pimp. After a group of local men beat up his main money maker (Silvana Corsini), he meets the more naive Stella (Franca Pasut), whom he starts dating with an eye toward perhaps converting into a prostitute as well. Meanwhile, he tries to establish a relationship with his son, but his estranged wife and her family want nothing to do with him. Filmed in black-and-white by master cinematographer Tonino Delli Colli, Accattone is highlighted by a series of memorable shots, from Accattone’s gorgeous dive from a bridge to a close-up of his face covered in sand, many of which were inspired by Baroque art and set to music by Bach. Written with Sergio Citti and featuring an assistant director named Bernardo Bertolucci — whose father was a friend of Pasolini’s — the story delves into the dire poverty in the slums of Rome, made all the more real by Pasolini’s use of both professional and nonprofessional actors. “Because he did not have much knowledge of film-making, he invented cinema. It was as though I had the privilege of assisting, of witnessing the invention of cinema by Pasolini,” Bertolucci later said of his experience. Accattone is screening November 26 as part of the Quad series “Pictures from the Revolution: Bertolucci’s Italian Period,” which runs November 24-30 and includes such other films that Bertolucci worked on, either as writer or director or in another capacity, as The Grim Reaper, Luna, Partner, 1900, the omnibus Love and Anger, and Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in the West.

Jean-Paul Trintignant tries to find his place in the world in Bernardo Bertolucci’s lush masterpiece, The Conformist

THE CONFORMIST (Bernardo Bertolucci, 1970)

Thursday, November 23, 1:00, 5:45

Saturday, November 25, 7:30

Wednesday, November 29, 9:20

quadcinema.com

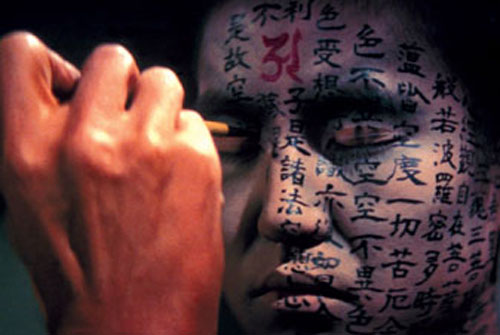

Based on the novel by Alberto Moravia, Bernardo Bertolucci’s gorgeous masterpiece, The Conformist, is a political thriller about paranoia, pedophilia, and trying to find one’s place in a changing world. Jean-Louis Trintignant (And God Created Woman, Z, My Night at Maud’s) stars as Marcello Clerici, a troubled man who suffered childhood traumas and is now attempting to join the fascist secret police. To prove his dedication to the movement, he is ordered to assassinate one of his former professors, the radical Luca Quadri (Enzo Tarascio), who is living in France. He falls for Quadri’s much younger wife, Anna (Dominique Sanda), who takes an intriguing liking to Clerici’s wife, Giulia (Stefania Sandrelli), while Manganiello (Gastone Moschin) keeps a close watch on him, making sure he will carry out his assignment. The Conformist, made just after The Spider’s Stragagem and followed by Last Tango in Paris, captures one man’s desperate need to belong, to become a part of Mussolini’s fascist society and feel normal at the expense of his real inner feelings and beliefs. An atheist, he goes to church to confess because Giulia demands it. A bureaucrat, he is not a cold-blooded killer, but he will murder a part of his past in order to be accepted by the fascists (as well as Bertolucci’s own past, as he makes a sly reference to his former mentor, Jean-Luc Godard, by using the French auteur’s phone number and address for Quadri’s). Production designer Ferdinando Scarfiotti and cinematographer Vittorio Storaro bathe the film in lush Art Deco colors as Bertolucci moves the story, told in flashbacks, through a series of set pieces that include an erotic dance by Anna and Giulia, a Kafkaesque visit to a government ministry, and a stunning use of black and white and light and shadow as Marcello and Giulia discuss their impending marriage. A multilayered psychological examination of a complex figure living in complex times, as much about the 1930s as the 1970s, as the youth of the Western world sought personal, political, and sexual freedom, The Conformist is screening at the Quad on November 23, 25, and 29.

Based on the novel by Alberto Moravia, Bernardo Bertolucci’s gorgeous masterpiece, The Conformist, is a political thriller about paranoia, pedophilia, and trying to find one’s place in a changing world. Jean-Louis Trintignant (And God Created Woman, Z, My Night at Maud’s) stars as Marcello Clerici, a troubled man who suffered childhood traumas and is now attempting to join the fascist secret police. To prove his dedication to the movement, he is ordered to assassinate one of his former professors, the radical Luca Quadri (Enzo Tarascio), who is living in France. He falls for Quadri’s much younger wife, Anna (Dominique Sanda), who takes an intriguing liking to Clerici’s wife, Giulia (Stefania Sandrelli), while Manganiello (Gastone Moschin) keeps a close watch on him, making sure he will carry out his assignment. The Conformist, made just after The Spider’s Stragagem and followed by Last Tango in Paris, captures one man’s desperate need to belong, to become a part of Mussolini’s fascist society and feel normal at the expense of his real inner feelings and beliefs. An atheist, he goes to church to confess because Giulia demands it. A bureaucrat, he is not a cold-blooded killer, but he will murder a part of his past in order to be accepted by the fascists (as well as Bertolucci’s own past, as he makes a sly reference to his former mentor, Jean-Luc Godard, by using the French auteur’s phone number and address for Quadri’s). Production designer Ferdinando Scarfiotti and cinematographer Vittorio Storaro bathe the film in lush Art Deco colors as Bertolucci moves the story, told in flashbacks, through a series of set pieces that include an erotic dance by Anna and Giulia, a Kafkaesque visit to a government ministry, and a stunning use of black and white and light and shadow as Marcello and Giulia discuss their impending marriage. A multilayered psychological examination of a complex figure living in complex times, as much about the 1930s as the 1970s, as the youth of the Western world sought personal, political, and sexual freedom, The Conformist is screening at the Quad on November 23, 25, and 29.

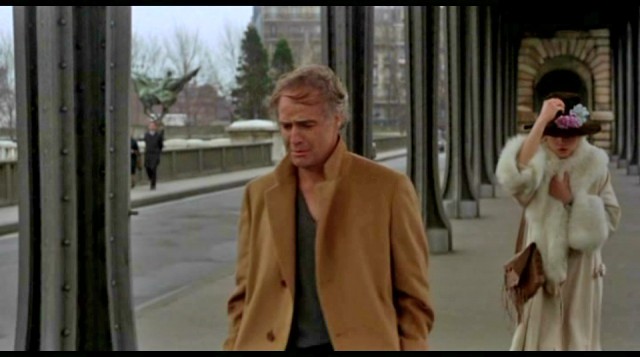

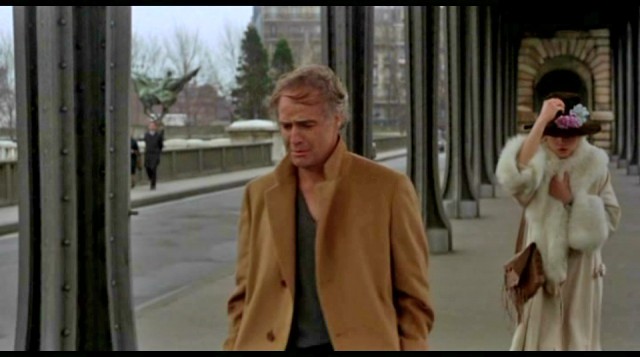

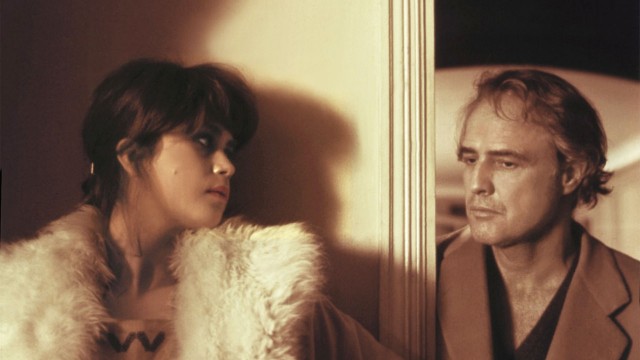

Marlon Brando and Maria Schneider star in Bernardo Bertolucci’s controversial Last Tango in Paris

LAST TANGO IN PARIS (ULTIMO TANGO A PARIGI) (Bernardo Bertolucci, 1972)

Thursday, November 23, 3:15, 8:00

Tuesday, November 28, 9:10

quadcinema.com

One of the most artistic films ever made about seduction, Bernardo Bertolucci’s X-rated Last Tango in Paris is also one of the most controversial. Written by Bertolucci with regular collaborator and editor Franco Arcalli and with French dialogue by Agnès Varda (Le Bonheur, Vagabond), the film opens with credits featuring jazzy romantic music by Argentine saxophonist Gato Barbieri and two colorful and dramatic paintings by Francis Bacon, “Double Portrait of Lucian Freud and Frank Auerbach” and “Study for a Portrait,” that set the stage for what is to follow. (Bacon was a major influence on the look and feel of the film, photographed by Vittorio Storaro.) Bertolucci then cuts to a haggard man (Marlon Brando) standing under the Pont de Bir-Hakeim in Paris, screaming out, “Fucking God!” His hair disheveled, he is wearing a long brown jacket and seems to be holding back tears. An adorable young woman (Maria Schneider) in a fashionable fluffy white coat and black hat with flowers passes by, stops and looks at him, then moves on. They meet again inside a large, sparsely furnished apartment at the end of Rue Jules Verne that they are each interested in renting. Both looking for something else in life, they quickly have sex and roll over on the floor, exhausted. For the next three days, they meet in the apartment for heated passion that the man, Paul, insists include nothing of the outside world — no references to names or places, no past, no present, no future; the young woman, Jeanne, agrees. Their sex goes from gentle and touching to brutal and animalistic; in fact, after one session, Bertolucci cuts to actual animals. The film is nothing if not subtle.

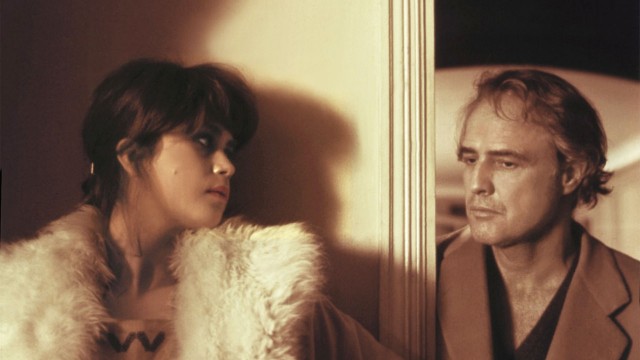

Jeanne (Maria Schneider) and Paul (Marlon Brando) share a private, sexual relationship in Last Tango in Paris

The lovers’ real lives are revealed in bits and pieces, as Paul tries to recover from his wife’s suicide and Jeanne deals with a fiancée, Thomas (Jean-Pierre Léaud), who has suddenly decided to make a film about them, without her permission, asking precisely the kind of questions that Paul never wants to talk about. When away from the apartment, Jeanne is shown primarily in the bright outdoors, flitting about fancifully and giving Thomas a hard time; in one of the only scenes in which she’s inside, Thomas makes a point of opening up several doors, preventing her from ever feeling trapped. Meanwhile, Paul is seen mostly in tight, dark spaces, especially right after having a fight with his dead wife’s mother. He walks into his hotel’s dark hallway, the only light coming from two of his neighbors as they open their doors just a bit to spy on him. Not saying anything, he pulls their doors shut as the screen goes from light to dark to light to dark again, and then Bertolucci cuts to Paul and Jeanne’s apartment door as she opens it, ushering in the brightness that always surrounds her. It’s a powerful moment that heightens the difference between the older, less hopeful man and the younger, eager woman. Inevitably, however, the safety of their private, primal relationship is threatened, and tragedy awaits.

Jeanne and Paul develop a complicated sexual relationship in controversial Bertolucci film

“I’ve tried to describe the impact of a film that has made the strongest impression on me in almost twenty years of reviewing. This is a movie people will be arguing about, I think, for as long as there are movies,” Pauline Kael wrote in the New Yorker on October 28, 1972, shortly before Last Tango closed the tenth New York Film Festival. “It is a movie you can’t get out of your system, and I think it will make some people very angry and disgust others. I don’t believe that there’s anyone whose feelings can be totally resolved about the sex scenes and the social attitudes in this film.” More than forty years later, the fetishistic Last Tango in Paris still has the ability to evoke those strong emotions. The sex scenes range from tender, as when Jeanne tells Paul they should try to climax without touching, to when Paul uses butter in an attack that was not scripted and about which Schneider told the Daily Mail in 2007, “I felt humiliated and to be honest, I felt a little raped, both by Marlon and by Bertolucci. After the scene, Marlon didn’t console me or apologise. Thankfully, there was just one take.” At the time of the shooting, Brando was forty-eight and Schneider nineteen; Last Tango was released between The Godfather and Missouri Breaks, in which Brando starred with Jack Nicholson, while Schneider would go on to make Michelangelo Antonioni’s The Passenger with Nicholson in 1975. Brando died in 2004 at the age of eighty, leaving behind a legacy of more than forty films. Schneider died in 2011 at the age of fifty-eight; she also appeared in more than forty films, but she was never able to escape the associations that followed her after her breakthrough performance in Last Tango, which featured extensive nudity, something she refused to do ever again. Even in 2014, Last Tango in Paris is both sexy and shocking, passionate and provocative, alluring and disturbing, all at the same time, a movie that, as Kael said, viewers won’t easily be able to get out of their system. Last Tango in Paris is screening at the Quad November 23 and 28.

Director Abel Ferrara packs a whole lot into controversial Italian writer and filmmaker Pier Paolo Pasolini’s last day on earth in the multinational coproduction Pasolini. Unfortunately, it all ends up a rather confusing jumble, with Ferrara (Bad Lieutenant, The Addiction) and screenwriter Maurizio Braucci (Gomorrah, Black Souls) squeezing too much into too little. Willem Dafoe stars as Pasolini on November 2, 1975, as the director is interviewed by a journalist, reads the newspaper on the couch, sits down at his typewriter to work on his novel Petrolio, edits what would be his final film (Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom), and goes cruising to pick up a young stud. Ferrara adds enactments of scenes from the never-realized Porno-Teo-Kolossal, with Pasolini’s real-life lover, Ninetto Davoli, playing the fictional character Epifanio. (Davoli was supposed to play the younger Nunzio in the hallucinatory tale, about a search for faith and the messiah. Davoli is played by Riccardo Scamarcio in Ferrara’s film.) Ferrara never really delves into the internal makeup of Pasolini (The Gospel According to Matthew, Teorema), an openly gay outspoken social and political activist, poet, Marxist, Christian, and documentarian, instead using brief episodes that only touch the surface, as if Dafoe is playing a character based on Pasolini rather than the complex man who was indeed Pasolini. But Ferrara does get very specific about Pasolini’s mysterious, brutal death. Pasolini is screening May 3 at 7:00 in the MoMA series “Abel Ferrara: Unrated” and will be followed by a Q&A with the director and Dafoe.

Director Abel Ferrara packs a whole lot into controversial Italian writer and filmmaker Pier Paolo Pasolini’s last day on earth in the multinational coproduction Pasolini. Unfortunately, it all ends up a rather confusing jumble, with Ferrara (Bad Lieutenant, The Addiction) and screenwriter Maurizio Braucci (Gomorrah, Black Souls) squeezing too much into too little. Willem Dafoe stars as Pasolini on November 2, 1975, as the director is interviewed by a journalist, reads the newspaper on the couch, sits down at his typewriter to work on his novel Petrolio, edits what would be his final film (Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom), and goes cruising to pick up a young stud. Ferrara adds enactments of scenes from the never-realized Porno-Teo-Kolossal, with Pasolini’s real-life lover, Ninetto Davoli, playing the fictional character Epifanio. (Davoli was supposed to play the younger Nunzio in the hallucinatory tale, about a search for faith and the messiah. Davoli is played by Riccardo Scamarcio in Ferrara’s film.) Ferrara never really delves into the internal makeup of Pasolini (The Gospel According to Matthew, Teorema), an openly gay outspoken social and political activist, poet, Marxist, Christian, and documentarian, instead using brief episodes that only touch the surface, as if Dafoe is playing a character based on Pasolini rather than the complex man who was indeed Pasolini. But Ferrara does get very specific about Pasolini’s mysterious, brutal death. Pasolini is screening May 3 at 7:00 in the MoMA series “Abel Ferrara: Unrated” and will be followed by a Q&A with the director and Dafoe.

Abel Ferrara’s third film, following the 1976 pornographic 9 Lives of a Wet Pussy Cat and the 1979 gorefest The Driller Killer, is a low-budget grindhouse female revenge fantasy set on the gritty streets of New York City. In Ms. 45 (also known as Angel of Vengeance), Zoë Tamerlis Lund makes her screen debut as Thana, a mute woman working as a seamstress in the Garment District. After being raped twice in one day on separate occasions, she soon goes all Death Wish / Taxi Driver on men seeking a little more from women. Thana — named after Freud’s death instinct, Thanatos, the opposite of the sex instinct, Eros — grabs herself a .45 and quickly proves she is one helluva shot as she goes out in search of potential victims in Chinatown, Central Park, and the very place where Woody Allen and Diane Keaton sat on a bench, romantically looking out at the Queensboro Bridge in an iconic moment from Manhattan. Ferrara, who plays the masked rapist, captures the nightmarish feel of the city at the time, where danger could be lurking around any corner, with the help of James Lemmo’s lurid, pornlike cinematography and Joe Delia’s jazz-disco soundtrack. Lund would go on to cowrite Ferrara’s Bad Lieutenant, in which she plays a junkie named Zoë, before drugs killed her in 1999 at the age of thirty-seven. Ms. 45 is a cult classic that keeps getting better with age — and yes, that is a man dressed as Mr. Met at the Halloween party. A new digital restoration will be screening May 7 and 11 in the MoMA series “Abel Ferrara: Unrated,” which runs May 1-31 and includes such other Ferrara works as The Addiction, Welcome to New York, Body Snatchers, King of New York, Fear City, Bad Lieutenant, The Funeral, and his latest, The Projectionist. Ferrara will be at MoMA to participate in discussions following several screenings the first week.

Abel Ferrara’s third film, following the 1976 pornographic 9 Lives of a Wet Pussy Cat and the 1979 gorefest The Driller Killer, is a low-budget grindhouse female revenge fantasy set on the gritty streets of New York City. In Ms. 45 (also known as Angel of Vengeance), Zoë Tamerlis Lund makes her screen debut as Thana, a mute woman working as a seamstress in the Garment District. After being raped twice in one day on separate occasions, she soon goes all Death Wish / Taxi Driver on men seeking a little more from women. Thana — named after Freud’s death instinct, Thanatos, the opposite of the sex instinct, Eros — grabs herself a .45 and quickly proves she is one helluva shot as she goes out in search of potential victims in Chinatown, Central Park, and the very place where Woody Allen and Diane Keaton sat on a bench, romantically looking out at the Queensboro Bridge in an iconic moment from Manhattan. Ferrara, who plays the masked rapist, captures the nightmarish feel of the city at the time, where danger could be lurking around any corner, with the help of James Lemmo’s lurid, pornlike cinematography and Joe Delia’s jazz-disco soundtrack. Lund would go on to cowrite Ferrara’s Bad Lieutenant, in which she plays a junkie named Zoë, before drugs killed her in 1999 at the age of thirty-seven. Ms. 45 is a cult classic that keeps getting better with age — and yes, that is a man dressed as Mr. Met at the Halloween party. A new digital restoration will be screening May 7 and 11 in the MoMA series “Abel Ferrara: Unrated,” which runs May 1-31 and includes such other Ferrara works as The Addiction, Welcome to New York, Body Snatchers, King of New York, Fear City, Bad Lieutenant, The Funeral, and his latest, The Projectionist. Ferrara will be at MoMA to participate in discussions following several screenings the first week.

After collaborating on a number of works by such auteurs as Mauro Bolognini and Federico Fellini, poet and novelist Pier Paolo Pasolini made his directorial debut in 1961 with the gritty, not-quite-neo-realist Accattone (“scrounger” or “beggar”). Somewhat related to his books Ragazzi di vita and Una vita violenta, the film is set in the Roman borgate, where brash young Vittorio “Accattone” Cataldi (Franco Citti) survives by taking crazy bets — like swimming across a river known for swallowing up people’s lives — and working as a pimp. After a group of local men beat up his main money maker (Silvana Corsini), he meets the more naive Stella (Franca Pasut), whom he starts dating with an eye toward perhaps converting into a prostitute as well. Meanwhile, he tries to establish a relationship with his son, but his estranged wife and her family want nothing to do with him. Filmed in black-and-white by master cinematographer Tonino Delli Colli, Accattone is highlighted by a series of memorable shots, from Accattone’s gorgeous dive from a bridge to a close-up of his face covered in sand, many of which were inspired by Baroque art and set to music by Bach. Written with Sergio Citti and featuring an assistant director named Bernardo Bertolucci — whose father was a friend of Pasolini’s — the story delves into the dire poverty in the slums of Rome, made all the more real by Pasolini’s use of both professional and nonprofessional actors. “Because he did not have much knowledge of film-making, he invented cinema. It was as though I had the privilege of assisting, of witnessing the invention of cinema by Pasolini,” Bertolucci later said of his experience. Accattone is screening November 26 as part of the Quad series “Pictures from the Revolution: Bertolucci’s Italian Period,” which runs November 24-30 and includes such other films that Bertolucci worked on, either as writer or director or in another capacity, as The Grim Reaper, Luna, Partner, 1900, the omnibus Love and Anger, and Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in the West.

After collaborating on a number of works by such auteurs as Mauro Bolognini and Federico Fellini, poet and novelist Pier Paolo Pasolini made his directorial debut in 1961 with the gritty, not-quite-neo-realist Accattone (“scrounger” or “beggar”). Somewhat related to his books Ragazzi di vita and Una vita violenta, the film is set in the Roman borgate, where brash young Vittorio “Accattone” Cataldi (Franco Citti) survives by taking crazy bets — like swimming across a river known for swallowing up people’s lives — and working as a pimp. After a group of local men beat up his main money maker (Silvana Corsini), he meets the more naive Stella (Franca Pasut), whom he starts dating with an eye toward perhaps converting into a prostitute as well. Meanwhile, he tries to establish a relationship with his son, but his estranged wife and her family want nothing to do with him. Filmed in black-and-white by master cinematographer Tonino Delli Colli, Accattone is highlighted by a series of memorable shots, from Accattone’s gorgeous dive from a bridge to a close-up of his face covered in sand, many of which were inspired by Baroque art and set to music by Bach. Written with Sergio Citti and featuring an assistant director named Bernardo Bertolucci — whose father was a friend of Pasolini’s — the story delves into the dire poverty in the slums of Rome, made all the more real by Pasolini’s use of both professional and nonprofessional actors. “Because he did not have much knowledge of film-making, he invented cinema. It was as though I had the privilege of assisting, of witnessing the invention of cinema by Pasolini,” Bertolucci later said of his experience. Accattone is screening November 26 as part of the Quad series “Pictures from the Revolution: Bertolucci’s Italian Period,” which runs November 24-30 and includes such other films that Bertolucci worked on, either as writer or director or in another capacity, as The Grim Reaper, Luna, Partner, 1900, the omnibus Love and Anger, and Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in the West.

Based on the novel by Alberto Moravia, Bernardo Bertolucci’s gorgeous masterpiece, The Conformist, is a political thriller about paranoia, pedophilia, and trying to find one’s place in a changing world. Jean-Louis Trintignant (And God Created Woman, Z, My Night at Maud’s) stars as Marcello Clerici, a troubled man who suffered childhood traumas and is now attempting to join the fascist secret police. To prove his dedication to the movement, he is ordered to assassinate one of his former professors, the radical Luca Quadri (Enzo Tarascio), who is living in France. He falls for Quadri’s much younger wife, Anna (Dominique Sanda), who takes an intriguing liking to Clerici’s wife, Giulia (Stefania Sandrelli), while Manganiello (Gastone Moschin) keeps a close watch on him, making sure he will carry out his assignment. The Conformist, made just after The Spider’s Stragagem and followed by Last Tango in Paris, captures one man’s desperate need to belong, to become a part of Mussolini’s fascist society and feel normal at the expense of his real inner feelings and beliefs. An atheist, he goes to church to confess because Giulia demands it. A bureaucrat, he is not a cold-blooded killer, but he will murder a part of his past in order to be accepted by the fascists (as well as Bertolucci’s own past, as he makes a sly reference to his former mentor, Jean-Luc Godard, by using the French auteur’s phone number and address for Quadri’s). Production designer Ferdinando Scarfiotti and cinematographer Vittorio Storaro bathe the film in lush Art Deco colors as Bertolucci moves the story, told in flashbacks, through a series of set pieces that include an erotic dance by Anna and Giulia, a Kafkaesque visit to a government ministry, and a stunning use of black and white and light and shadow as Marcello and Giulia discuss their impending marriage. A multilayered psychological examination of a complex figure living in complex times, as much about the 1930s as the 1970s, as the youth of the Western world sought personal, political, and sexual freedom, The Conformist is screening at the Quad on November 23, 25, and 29.

Based on the novel by Alberto Moravia, Bernardo Bertolucci’s gorgeous masterpiece, The Conformist, is a political thriller about paranoia, pedophilia, and trying to find one’s place in a changing world. Jean-Louis Trintignant (And God Created Woman, Z, My Night at Maud’s) stars as Marcello Clerici, a troubled man who suffered childhood traumas and is now attempting to join the fascist secret police. To prove his dedication to the movement, he is ordered to assassinate one of his former professors, the radical Luca Quadri (Enzo Tarascio), who is living in France. He falls for Quadri’s much younger wife, Anna (Dominique Sanda), who takes an intriguing liking to Clerici’s wife, Giulia (Stefania Sandrelli), while Manganiello (Gastone Moschin) keeps a close watch on him, making sure he will carry out his assignment. The Conformist, made just after The Spider’s Stragagem and followed by Last Tango in Paris, captures one man’s desperate need to belong, to become a part of Mussolini’s fascist society and feel normal at the expense of his real inner feelings and beliefs. An atheist, he goes to church to confess because Giulia demands it. A bureaucrat, he is not a cold-blooded killer, but he will murder a part of his past in order to be accepted by the fascists (as well as Bertolucci’s own past, as he makes a sly reference to his former mentor, Jean-Luc Godard, by using the French auteur’s phone number and address for Quadri’s). Production designer Ferdinando Scarfiotti and cinematographer Vittorio Storaro bathe the film in lush Art Deco colors as Bertolucci moves the story, told in flashbacks, through a series of set pieces that include an erotic dance by Anna and Giulia, a Kafkaesque visit to a government ministry, and a stunning use of black and white and light and shadow as Marcello and Giulia discuss their impending marriage. A multilayered psychological examination of a complex figure living in complex times, as much about the 1930s as the 1970s, as the youth of the Western world sought personal, political, and sexual freedom, The Conformist is screening at the Quad on November 23, 25, and 29.