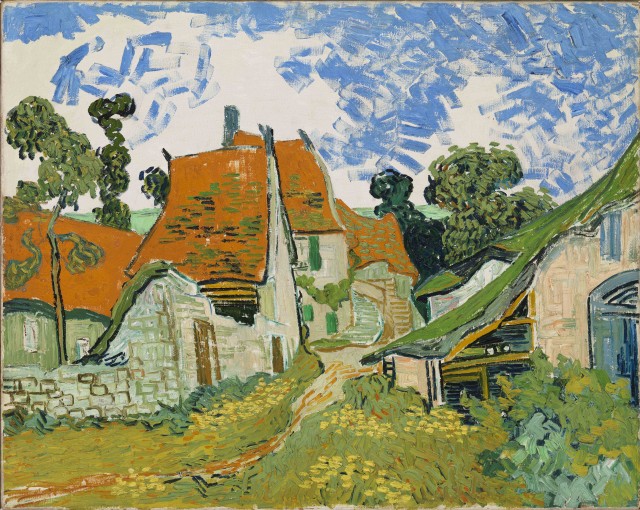

Vincent van Gogh, “Street in Auvers-sur-Oise,” oil on canvas, 1890 (Ateneum Art Museum, Finnish National Gallery, Helsinki, Collection Antell)

The Met Breuer

945 Madison Ave. at 75th St.

Tuesday – Sunday through September 4, suggested admission $12-$25

212-731-1675

www.metmuseum.org

In Mr. Turner, Mike Leigh’s 2014 biopic about British artist J. M. W. Turner, the controversial landscape painter (played with a splendid curmudgeonly gruffness by Timothy Spall) examines a canvas of his hanging at the Royal Academy, approaches it with his brush, and dabs on one last bit of color, as if adding a period to complete the painting. But what really determines whether a work of art is finished? That is the question asked by the Met Breuer in its inaugural exhibition, “Unfinished: Thoughts Left Visible.” The show, which features nearly two hundred paintings, drawings, and sculptures, explores various aspects of completion while referencing the Met’s takeover of Marcel Breuer’s building, originally built for the Whitney, which recently moved to its new home in the Meatpacking District. (At the very least, the downstairs of the Met Breuer has not been finished.) “A work is complete if in it the master’s intentions have been realized,” Rembrandt said. However, Pablo Picasso asserted, “To finish a picture? What nonsense! To finish it means to be through with it, to kill it, to rid it of its soul.” The exhibition, spread across two floors, includes several canvases by Rembrandt and Picasso as well as works by Titian, Pollock, Velázquez, Monet, Homer, Whistler, Friedrich, Hesse, Gericault, Ruscha, Bourgeois, Cézanne, Sargent, Matisse, Szapocznikow, Tuymans, Richter, Johns, Twombly, Dumas, and many others, from the Renaissance to the present, a fascinating journey into the creative process. But the majority of the pieces on view — divided into such sections as “The Infinite: Art Out of Bounds,” “To Be Determined: Painting in Process,” and “Decay, Dwindle, Decline” — are not immediately identifiable as being incomplete, especially given curators Andrea Bayer, Kelly Baum, and Nicholas Cullinan’s wide employment of the concept of “unfinished.”

Janine Antoni, “Lick and Lather,” chocolate and soap, 1993-94 (collection of Jill and Peter Kraus)

Edouard Manet kept repainting the face of “Madame Edouard Manet” and eventually gave up, not satisfied with the results. James Tissot’s “Orphan” etching was made from a painting that is now lost. Elizabeth Peyton’s “Napoleon (After Louis David, Le General Bonaparte vers 1797)” was based on an unfinished portrait by Jacques Louis David. Lucian Freud continually reworked the face in a 2002 self-portrait with oil paint, leaving the rest of the canvas as a charcoal sketch. Gustave Courbet chose not to give definition to his visage in “The Homecoming.” Alberto Giacometti made significant changes to “Annette” after it was first shown publicly. Edvard Munch’s “Self-Portrait with Wounded Eye” is an unsigned piece that mirrors the vision problem the artist was suffering from. Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s “The Dirty Bride or The Wedding of Mopsus and Nisa” was a design for a woodcut. Gustav Klimt’s “Posthumous Portrait of Ria Munk III” was commissioned half a dozen years after the subject committed suicide, and then Klimt died before it was complete. Janine Antoni licked and washed with the two busts of “Lick and Lather,” but the materials she used (chocolate and soap) will eventually disintegrate on their own. It is not known why Albrecht Dürer did not finish “Salvator Mundi” after he fled Nuremberg for Venice and later returned. Camille Corot’s “Boatman among the Reeds,” a finished work, looks unfinished when seen from up close; one critic noted, “When you come to a Corot, it is better not to get too close. Nothing is finished, nothing is carried through. . . . Keep your distance.” Meanwhile, X-radiographs have revealed an earlier state underneath Corot’s signed “Sibylle.” Vincent van Gogh committed suicide before completing “Street in Auvers-sur-Oise.” Edgar Degas reworked the 1866 “Scene from the Steeplechase: The Fallen Jockey” in 1880-81 and again around 1897; the artist reportedly said to Katherine Cassat, mother of Mary Cassat, “It is one of those works which are sold after a man’s death and artists buy them not caring whether they are finished or not.” Indeed, the nature of death, the ultimate finality, hovers over many of the works. “The painting raises fundamental questions regarding the transitional nature of the moment of death and the inherent ‘unfinishedness’ of human life,” the wall label says about Ferdinand Hodler’s “Valentine Godé — Darel on Her Deathbed,” a poignant oil depicting the Swiss artist’s ailing lover.

Joseph Mallord William Turner, “Rough Sea,” oil on canvas, ca. 1840-45 (Tate: Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856)

The centerpiece of the show is a side room — missed by many museumgoers — that contains five glorious later canvases by Joseph Mallard William Turner, abstract seascapes and landscapes painted between 1835 and 1845. Pre-Impressionist, they seem to stand at a sort of gateway to the modern and a transition between earlier ideas of “unfinished” related to product and later notions associated with process. There are few definable objects in the works — “Margate (?), from the Sea,” “The Thames above Waterloo Bridge,” “Rough Sea,” “Sun Setting over a Lake,” and “Sunset from the Top of the Rigi” — and there is debate over whether they are non finito (intentionally unfinished), never completed for various reasons, or in fact finished paintings. Given the experimental nature of the glowing canvases, it wouldn’t have surprised me if Spall walked into the room, carefully surveyed the canvases, then added a dab of paint here, a splotch of color there. It also makes one question whether it even matters if a work is finished or not; without knowing any of the background behind these five Turner paintings, you’d be hard-pressed to consider them unfinished; Turner’s magnificent use of light and color and exquisite brushwork take your breath away, filling every bit of you with emotion, leaving nothing untouched, even if, to Turner, they were not done. As Barnett Newman said, “The idea of a ‘finished’ picture is a fiction.”

The exhibition finishes September 4; be sure to also check out Tatsuo Miyajima’s first-floor installation, “Arrow of Time (Unfinished Life),” which was specially commissioned as a companion piece for the show; it consists of approximately 250 red, numeric LEDs hanging from the ceiling, counting down from nine to one over and over at different intervals, an endless cycle evoking life, death, and rebirth. Miyajima named the piece after Sir Arthur Stanley Eddington’s theory concerning thermodynamics and entropy and was inspired by the Buddhist notion of samsara, which fits right in with the theme of the Breuer’s first major exhibit.

Jean-François Laguionie’s award-winning animated film, The Painting, has a very cool premise: The characters inside one of a painter’s works have organized a rigid class structure of the Alldunns, who have been completed and have sole access to the ritzy castle; the Halfies, who are not quite finished and are not allowed to join them; and the Sketchies, outlined figures who are terribly abused by the Alldunns. At the center of it all is an impossible Romeo and Juliet-like love story between the Alldunn Ramo (voiced by Adrien Larmande) and the Halfie Claire (Chloé Berthier). With the power-hungry Alldunns, led by the Great Chandelier (Jacques Roehrich), on the rampage, Ramo, the Sketchie known as Quill (Thierry Jahn), and Claire’s best friend, the Halfie Lola (Jessica Monceau), are on the run, trying to reunite the lovers and find the real-life painter so he can finish the Halfies and Sketchies and bring peace to the land. But soon they have fallen out of their painting and into the artist’s studio, where they meet characters from other works, including a reclining nude (Céline Ronte) and a self-portrait (Laguionie), and enter different canvases during their adventurous, and dangerous, search for the creator. Laguionie (Rowing Across the Atlantic, A Monkey’s Tale), who has been making animated films for five decades, has fun mimicking Modigliani, Matisse, Picasso, and other major artists, but his world-building doesn’t quite hold together as the characters continue on their colorful journey. He successfully walks that fine line between playful parable and melodramatic morality play, but things ultimately get away from him as the resolution nears. The Painting is screening December 30 at 6:15 at the IFC Center as part of the series “An Animated World: Celebrating 5 Years of GKIDS Classics,” paying tribute to GKIDS’ ongoing New York International Children’s Film Festival, which continues with such other animated works as Tono Errando, Javier Mariscal, and Fernando Trueba’s Chico & Rita, Goro Miyazaki’s From Up on Poppy Hill, and Jacques-Remy Girerd’s Mia and the Migoo.

Jean-François Laguionie’s award-winning animated film, The Painting, has a very cool premise: The characters inside one of a painter’s works have organized a rigid class structure of the Alldunns, who have been completed and have sole access to the ritzy castle; the Halfies, who are not quite finished and are not allowed to join them; and the Sketchies, outlined figures who are terribly abused by the Alldunns. At the center of it all is an impossible Romeo and Juliet-like love story between the Alldunn Ramo (voiced by Adrien Larmande) and the Halfie Claire (Chloé Berthier). With the power-hungry Alldunns, led by the Great Chandelier (Jacques Roehrich), on the rampage, Ramo, the Sketchie known as Quill (Thierry Jahn), and Claire’s best friend, the Halfie Lola (Jessica Monceau), are on the run, trying to reunite the lovers and find the real-life painter so he can finish the Halfies and Sketchies and bring peace to the land. But soon they have fallen out of their painting and into the artist’s studio, where they meet characters from other works, including a reclining nude (Céline Ronte) and a self-portrait (Laguionie), and enter different canvases during their adventurous, and dangerous, search for the creator. Laguionie (Rowing Across the Atlantic, A Monkey’s Tale), who has been making animated films for five decades, has fun mimicking Modigliani, Matisse, Picasso, and other major artists, but his world-building doesn’t quite hold together as the characters continue on their colorful journey. He successfully walks that fine line between playful parable and melodramatic morality play, but things ultimately get away from him as the resolution nears. The Painting is screening December 30 at 6:15 at the IFC Center as part of the series “An Animated World: Celebrating 5 Years of GKIDS Classics,” paying tribute to GKIDS’ ongoing New York International Children’s Film Festival, which continues with such other animated works as Tono Errando, Javier Mariscal, and Fernando Trueba’s Chico & Rita, Goro Miyazaki’s From Up on Poppy Hill, and Jacques-Remy Girerd’s Mia and the Migoo.

Orson Welles plays a masterful cinematic magician in the riotous F for Fake, a pseudo-documentary (or is it all true?) about art fakes and reality. Exploring slyly edited narratives involving art forger Elmyr de Hory, writer Clifford Irving, Spanish painter and sculptor Pablo Picasso, and reclusive billionaire Howard Hughes, the iconoclastic auteur is joined by longtime companion Oja Kodar and a cast of familiar faces in a fun ride that will leave viewers baffled — and thoroughly entertained. Welles manipulates the audience — and the process of filmmaking — with tongue firmly planted in cheek as he also references his own controversial legacy with nods to such classics as Citizen Kane and The Third Man. It’s both a love letter to the art of filmmaking as well as a warning to not always believe what you see, whether in books, on canvas, or, of course, at the movies. F for Fake is screening April 20 & 21 at noon as part of the new Nitehawk Cinema monthly series “Art Seen,” which continues May 18-19 with Ben Shapiro’s Gregory Crewdson: Brief Encounters and June 22-23 with The Cool School and Paul McCarthy’s The Black and White Tapes. Each program will begin with an “Artist Film Club” presentation that includes one video from the 2013 Moving Image Art Fair.

Orson Welles plays a masterful cinematic magician in the riotous F for Fake, a pseudo-documentary (or is it all true?) about art fakes and reality. Exploring slyly edited narratives involving art forger Elmyr de Hory, writer Clifford Irving, Spanish painter and sculptor Pablo Picasso, and reclusive billionaire Howard Hughes, the iconoclastic auteur is joined by longtime companion Oja Kodar and a cast of familiar faces in a fun ride that will leave viewers baffled — and thoroughly entertained. Welles manipulates the audience — and the process of filmmaking — with tongue firmly planted in cheek as he also references his own controversial legacy with nods to such classics as Citizen Kane and The Third Man. It’s both a love letter to the art of filmmaking as well as a warning to not always believe what you see, whether in books, on canvas, or, of course, at the movies. F for Fake is screening April 20 & 21 at noon as part of the new Nitehawk Cinema monthly series “Art Seen,” which continues May 18-19 with Ben Shapiro’s Gregory Crewdson: Brief Encounters and June 22-23 with The Cool School and Paul McCarthy’s The Black and White Tapes. Each program will begin with an “Artist Film Club” presentation that includes one video from the 2013 Moving Image Art Fair.