The Prince and the Dybbuk makes its U.S. premiere at the New York Jewish Film Festival

THE PRINCE AND THE DYBBUK (Piotr Rosolowski & Elwira Niewiera, 2017)

Film Society of Lincoln Center, Walter Reade Theater

165 West 65th St. at Amsterdam Ave.

Wednesday, January 10, 2:45, and Thursday, January 11, 9:00

Festival runs January 10-23

212-875-5601

www.filmlinc.org

prince-dybbuk.com

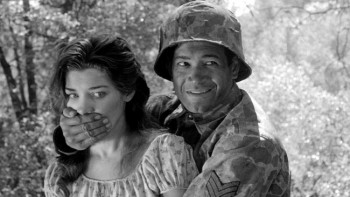

The New York Jewish Film Festival gets under way January 10 with an intriguing look at enigmatic filmmaker Michał Waszyński, the director of one of the most important Yiddish movies of all time, the 1937 supernatural tale The Dybbuk. In The Prince and the Dybbuk, directors Piotr Rosolowski and Elwira Niewiera find that discovering who Waszyński was is like chasing a ghost, as he continually reinvented himself while being haunted by a past he tried to erase. Like the characters in many of the films he produced and directed, he was constantly searching for his true identity as he journeyed from Poland and Germany to Italy and Spain. “He was in his world, so mysterious and exciting. Nobody really knows what he’s really like,” one of his assistant directors, Enrico Bergier, says. Throughout the eighty-minute documentary, friends, relatives, colleagues, and others describe Waszyński, who produced and/or directed nearly 150 films, as a gentleman, Jewish, Catholic, noble-minded, lonely, elegant and refined, an exceptional boss, generous, isolated, very smart, a larger-than-life character, an aristocrat, a bit strange, and a mythomaniac. He married a countess, dubbing himself the Polish Prince, and took one of his actors, Albin Ossowski, to gay restaurants. “He was longing for his youth,” Ossowski says. He hobnobbed with Orson Welles, Sophia Loren, Audrey Hepburn, and Claudia Cardinale. He appeared in Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s 1954 film, The Barefoot Contessa. He was singled out by Josef Goebbels as an enemy. He was involved with such 1960s blockbusters as El Cid and The Fall of the Roman Empire as well as smaller Eastern European films, most famously The Dybbuk, about a young bride possessed by a spirit. Rosolowski and Niewiera, who previously collaborated on the award-winning Domino Effect, include newsreel footage, family photos, home movies, a behind-the-scenes promotional piece narrated by James Mason about the making of Anthony Mann’s budget-busting The Fall of the Roman Empire, spoken excerpts from Waszyński’s diaries, and clips from such Waszyński films as His Excellency the Shop Assistant, Unknown Man of San Marino, Dvanáct kresel, Gehenna, Wielka Droga, Zabawka, and Znachor, many of which feature lost characters.

The New York Jewish Film Festival gets under way January 10 with an intriguing look at enigmatic filmmaker Michał Waszyński, the director of one of the most important Yiddish movies of all time, the 1937 supernatural tale The Dybbuk. In The Prince and the Dybbuk, directors Piotr Rosolowski and Elwira Niewiera find that discovering who Waszyński was is like chasing a ghost, as he continually reinvented himself while being haunted by a past he tried to erase. Like the characters in many of the films he produced and directed, he was constantly searching for his true identity as he journeyed from Poland and Germany to Italy and Spain. “He was in his world, so mysterious and exciting. Nobody really knows what he’s really like,” one of his assistant directors, Enrico Bergier, says. Throughout the eighty-minute documentary, friends, relatives, colleagues, and others describe Waszyński, who produced and/or directed nearly 150 films, as a gentleman, Jewish, Catholic, noble-minded, lonely, elegant and refined, an exceptional boss, generous, isolated, very smart, a larger-than-life character, an aristocrat, a bit strange, and a mythomaniac. He married a countess, dubbing himself the Polish Prince, and took one of his actors, Albin Ossowski, to gay restaurants. “He was longing for his youth,” Ossowski says. He hobnobbed with Orson Welles, Sophia Loren, Audrey Hepburn, and Claudia Cardinale. He appeared in Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s 1954 film, The Barefoot Contessa. He was singled out by Josef Goebbels as an enemy. He was involved with such 1960s blockbusters as El Cid and The Fall of the Roman Empire as well as smaller Eastern European films, most famously The Dybbuk, about a young bride possessed by a spirit. Rosolowski and Niewiera, who previously collaborated on the award-winning Domino Effect, include newsreel footage, family photos, home movies, a behind-the-scenes promotional piece narrated by James Mason about the making of Anthony Mann’s budget-busting The Fall of the Roman Empire, spoken excerpts from Waszyński’s diaries, and clips from such Waszyński films as His Excellency the Shop Assistant, Unknown Man of San Marino, Dvanáct kresel, Gehenna, Wielka Droga, Zabawka, and Znachor, many of which feature lost characters.

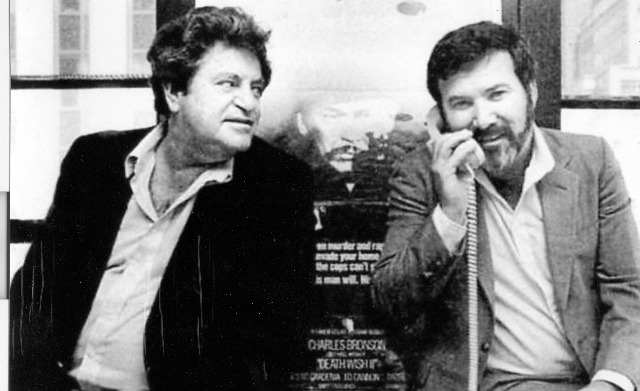

Enigmatic filmmaker Michał Waszyński (in red shirt) plays cards in Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s The Barefoot Contessa

Waszyński was born Moshe Waks in the village of Kovel in Poland (what is now Ukraine) in 1904 and later changed his name to Michał Waszyński and converted to Catholicism. Even when facts are revealed about him, there is no evidence about why he did the things he did in his personal life. “To me he was a great magician. He lived in a dream world, because cinema is a dream,” explains Maurizio Dickmann, a member of the Italian family that took him in. Later, in an Under the Flag of Love radio broadcast, Waszyński explains, “I do what I love. Cinema is my passion and it stimulates my intellect. . . . To me, film is like a second reality, subject to completely different rules. In a split second, a king can become a shepherd or a beggar a rich man.” His diaries divulge a dark side about his search for who he is and who he was as he transformed himself from shepherd to king. “My city vanishes from my mind, as if the place of my youth had never existed,” he writes. “But I can never rid myself of you. You were the one who abandoned us. Although, even now, in my dreams and when awake, you return to me every night, like a stab to the heart. You drive deep inside me. Like an evil spirit, you circle around me.” Waszyński was chased by spirits his entire life — he passed away suddenly in 1965 — and turned to the movies for answers, which only led to more questions. Named Best Documentary on Cinema at the Venice Film Festival, The Prince and the Dybbuk is making its U.S. premiere at the New York Jewish Film Festival, screening at the Walter Reade Theater on January 10 at 2:45 and January 11 at 9:00, preceded by Daria Martin’s short film A Hunger Artist, based on the Franz Kafka story. The January 11 screening will be followed by a Q&A with Rosolowski, Niewiera, and Martin. A copresentation of the Jewish Museum and the Film Society of Lincoln Center, the festival, which runs January 10-23, is also showing the world premiere of a brand-new restoration of The Dybbuk on January 14 and 17.

The 2017 New York Jewish Film Festival opens with the tender, emotionally wrenching Moon in the 12th House, the debut feature by Dorit Hakim, who won the 1998 Silver Lion for Best Short Film for her eleven-minute Small Change. Hakim, a journalist and filmmaker who was born in Tel Aviv, lived for several years with her husband, Israeli hi-tech success Shlomo Kramer, in Silicon Valley, then moved back to her homeland. For her first full-length work, she reaches deep into her Israeli youth to tell the story of two sisters separated by tragedy when they were girls. Now adults, the vain Mira (Yuval Scharf) works in a glitzy Tel Aviv nightclub, where she does drugs and sleeps with her selfish, mean-spirited boss, Doron (Gal Toren). Her younger sister, twenty-one-year-old Lenny (Yaara Pelzig), has chosen to remain in the family home in the country, taking care of their ailing father (Avraham Horovitz), who is in an assisted living facility after a stroke. Lenny, who goes for a precious swim every day to temporarily escape her overwhelming responsibilities, is also watching her neighbor’s teenage son, Ben (Gefen Barkai), while his artist mother is away. Long estranged, the sisters are reunited when a desperate Mira suddenly shows up on Lenny’s doorstep, but as much as Mira might need her, Lenny is not yet ready to accept her back in her life. “It’s not as easy for me as it is for you,” Mira says, not understanding the sacrifices that Lenny has made, part of the reason why they are estranged.

The 2017 New York Jewish Film Festival opens with the tender, emotionally wrenching Moon in the 12th House, the debut feature by Dorit Hakim, who won the 1998 Silver Lion for Best Short Film for her eleven-minute Small Change. Hakim, a journalist and filmmaker who was born in Tel Aviv, lived for several years with her husband, Israeli hi-tech success Shlomo Kramer, in Silicon Valley, then moved back to her homeland. For her first full-length work, she reaches deep into her Israeli youth to tell the story of two sisters separated by tragedy when they were girls. Now adults, the vain Mira (Yuval Scharf) works in a glitzy Tel Aviv nightclub, where she does drugs and sleeps with her selfish, mean-spirited boss, Doron (Gal Toren). Her younger sister, twenty-one-year-old Lenny (Yaara Pelzig), has chosen to remain in the family home in the country, taking care of their ailing father (Avraham Horovitz), who is in an assisted living facility after a stroke. Lenny, who goes for a precious swim every day to temporarily escape her overwhelming responsibilities, is also watching her neighbor’s teenage son, Ben (Gefen Barkai), while his artist mother is away. Long estranged, the sisters are reunited when a desperate Mira suddenly shows up on Lenny’s doorstep, but as much as Mira might need her, Lenny is not yet ready to accept her back in her life. “It’s not as easy for me as it is for you,” Mira says, not understanding the sacrifices that Lenny has made, part of the reason why they are estranged.

Named Best Canadian Feature at the 2014 Toronto International Film Festival and the closing-night selection of the 2015 New York Jewish Film Festival, Maxime Giroux’s Félix and Meira is a somber, reflective tale starring Israeli actress Hadas Yaron as Meira, a young married woman who is feeling trapped by the constraints of the Hasidic world in which she lives in Montreal’s Mile End district. Her husband, Shulem (Luzer Twersky), is a devout man who follows the tenets of his religion; he and Meira sleep in separate beds, and he seems more intent on ritualistically washing his hands in the bedroom than touching his wife. One morning, while pushing her daughter in a stroller, she is approached by Félix (Martin Dubreuil), a conflicted man whose father just died so he is seeking advice about God and death. Meira tells him to leave them alone, but soon Félix and Meira are meeting in secret, and when Shulem finds out about it, he ships Meira off to Brooklyn. Félix goes after her, wanting to take their relationship to the next level as Meira considers her responsibilities to her husband, her daughter, and herself.

Named Best Canadian Feature at the 2014 Toronto International Film Festival and the closing-night selection of the 2015 New York Jewish Film Festival, Maxime Giroux’s Félix and Meira is a somber, reflective tale starring Israeli actress Hadas Yaron as Meira, a young married woman who is feeling trapped by the constraints of the Hasidic world in which she lives in Montreal’s Mile End district. Her husband, Shulem (Luzer Twersky), is a devout man who follows the tenets of his religion; he and Meira sleep in separate beds, and he seems more intent on ritualistically washing his hands in the bedroom than touching his wife. One morning, while pushing her daughter in a stroller, she is approached by Félix (Martin Dubreuil), a conflicted man whose father just died so he is seeking advice about God and death. Meira tells him to leave them alone, but soon Félix and Meira are meeting in secret, and when Shulem finds out about it, he ships Meira off to Brooklyn. Félix goes after her, wanting to take their relationship to the next level as Meira considers her responsibilities to her husband, her daughter, and herself.