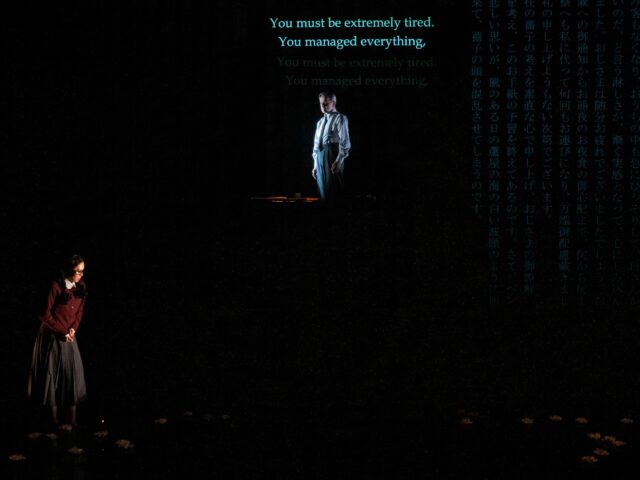

Josuke Misugi (Mikhail Baryshnikov) watches Shoko (Miki Nakatani) from above in The Hunting Gun (photo by Pasha Antono)

THE HUNTING GUN

Baryshnikov Arts Center, Jerome Robbins Theater

450 West 37th St. between Ninth & Tenth Aves.

Tuesday – Sunday through April 15, $35-$150

646-731-3200

thehuntinggun.org

bacnyc.org

Miki Nakatani is so mesmerizing in the US premiere of The Hunting Gun that even her costar, in a building named after him, can barely take his eyes off her.

Running in the Jerome Robbins Theater at Baryshnikov Arts Center through April 15, the haunting, heart-wrenchingly poetic play was adapted by Serge Lamothe from Yasushi Inoue’s 1949 novel centered around an illicit love affair that deeply affects four people. In a devastating, award-winning performance, Nakatani plays three roles: a girl named Shoko whose mother, Saiko, has just died; Midori, Saiko’s cousin and best friend; and Saiko herself, essentially communicating from the grave.

BAC founding artistic director Mikhail Baryshnikov is Josuke Misugi, a hunter who is married to Midori and had a long tryst with Saiko. The story unfolds as the three female characters read letters they’ve written to Misugi, who witnesses everything from an elevated platform at the back of the stage, behind three black translucent vertical screens with excerpts from the letters in Japanese on them. Each of the female characters wears a different outfit — the gorgeous clothing is by Renée April, with costume changes taking place onstage — while the floor of François Séguin’s eerie, mystical set magically changes for the three women, incorporating the elements of water, earth, and wood. David Finn’s lighting has a supernatural feel, as does Alexander MacSween’s music.

The premise is that Misugi has been moved by a poem he read in The Hunter’s Companion, a magazine not known for its literary prowess. “What made him cold, armed with white, bright steel, / To take the lives of creatures? / Attracted by the tall hunter’s back, / I looked and looked,” it says in part. “As the glittering of a hunting gun, / Stamping its weight on the lonely body, / Lonely mind of a middle-aged man, / Radiates a queer, austere beauty, / Never shown when aimed at life.”

Midori (Miki Nakatani) shares her deep pain in darkly poetic show at BAC (photo by Pasha Antono)

Misugi writes to the poet, believing that he, Misugi, is the lonely hunter the man describes in the poem. He tells him he is going to send him three letters he has received, which he was going to burn. “I would be happy if you would read them at your leisure,” he explains to the author. “It seems to me that a man is foolish enough to want another person to understand him. After you have read them, I hope you’ll burn the three of them for me.” The trio of women then perform the poems while Misugi watches closely from above and carefully cleans his Churchill shotgun.

At first Shoko thanks Misugi for his help after her mother’s death, writing, “I’ve thought and thought about how to say all this, and I have finished, so to speak, the preparation for this letter. But when I pick up my pen, all sorts of sorrows come rushing upon me from every direction, like the white waves at Ashiya on windy days, and these sorrows confuse me.” Her world has been turned inside out since she read her mother’s diaries and found out about the affair. “That love which can’t be kept without being sinful must be a sorrowful thing,” she opines.

Demonstrating her inner strength, Midori begins her letter, “When I write your name in this formal way, I feel my heart throbbing with emotion as though I were writing a love letter. I have written scores of such letters during the last thirteen years, sometimes secretly, sometimes openly, but among all of them not one has been addressed to you. Why? That realization makes me feel an oddness I can’t explain logically. Don’t you also think this is funny?”

Saiko’s letter retraces some of the adventures she and Misugi had together while also explaining, “Many hours or many days after I’m gone and have turned into nothing, you will read this letter. And living after me, it will tell you the many thoughts I had when I was alive. As though I were speaking to you, this letter will tell you what I thought and felt — things you don’t yet know. And it will be as though you were talking to me and hearing my voice.”

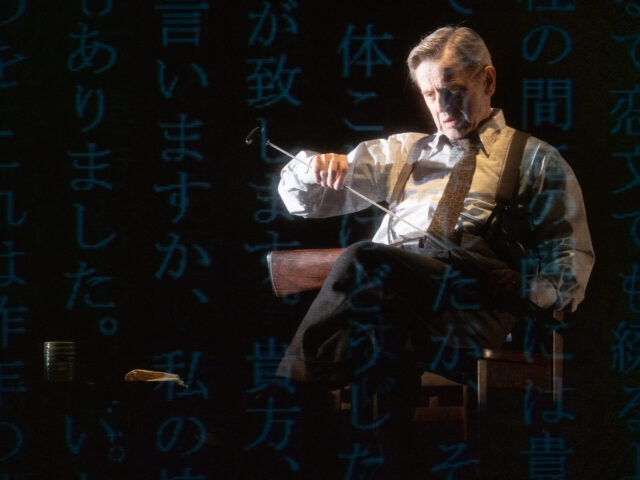

Josuke Misugi (Mikhail Baryshnikov) cleans his rifle throughout The Hunting Gun (photo by Pasha Antono)

Nakatani (When the Last Sword Is Drawn, Memories of Matsuko, Zero Focus) cautiously roams across the stage as if a butoh dancer, moving almost exasperatingly slowly, delivering the words from the letters like they’re the lily pads or stones beneath her feet. At times it’s like she’s floating, a ghost reliving her characters’ past tinged with a wide range of conflicting emotions.

Baryshnikov (Brodsky/Baryshnikov, The Orchard) sits in a chair, rises, and turns his attention from the Churchill to Nakatani with a master’s touch, his eyes and body understanding precisely how Misugi’s actions impacted Shoko, Midori, and Saiko. He might not speak a word, but his minimal gestures depict anguish and contrition with the skill of an exquisite dancer as Misugi, disengaged from reality, finally sees the pain he has caused others and raises the now pristine rifle.

François Girard, who has made such films as The Red Violin, Thirty Two Short Films About Glenn Gould, and Silk (costarring Nakatani) in addition to helming numerous operas and theater productions, directs The Hunting Gun with the discipline of a Zen master, allowing the details of the story, which has previously been made into a 1961 melodrama by Heinosuke Gosho and a 2018 opera by Thomas Larcher, to unfold like a butterfly or a bee flitting across a blossoming garden. It is a profoundly sad tale, filled with regret, revenge, and remorse, told with an otherworldly elegance and grace.

It is also a fitting prelude to “Mikhail Baryshnikov at 75: A Day of Music and Celebration,” in which Misha will be honored by Laurie Anderson, Diana Krall, Regina Spektor, Kaoru Watanabe, Mark Morris, and Anna Baryshnikov (his daughter) at Kaatsbaan Cultural Park on June 25; tickets ($75-$500) are available here.

We called Tetsuya Nakashima’s 2004 hit, Kamikaze Girls, the “otaku version of Jean-Pierre Jeunet’s Amelie,” referring to it as “fresh,” “frenetic,” “fast-paced,” and “very funny.” His feature-length follow-up, the stunningly gorgeous Memories of Matsuko, also recalls Amelie and all those other adjectives, albeit with much more sadness. Miki Nakatani (Ring, Silk) stars as Matsuko, a sweet woman who spent her life just looking to be loved but instead found nothing but heartbreak, deception, and physical and emotional abuse. But Memories of Matsuko, is not a depressing melodrama, even if Nakashima (Confessions, The World of Kanako) incorporates touches of Douglas Sirk every now and again. The film is drenched in glorious Technicolor, often breaking out into bright and cheerful musical numbers straight out of a 1950s fantasy world. As the movie begins, Matsuko has been found murdered, and her long-estranged brother (Akira Emoto) has sent his son, Sho (Eita), who never knew she existed, to clean out her apartment. As Sho goes through the mess she left behind, the film flashes back to critical moments in Matsuko’s life — and he also meets some crazy characters in the present. It’s difficult rooting for the endearing Matsuko knowing what becomes of her, but Nakashima’s remarkable visual style will grab you and never let go. And like Audrey Tatou in Amelie, Nakatani — who won a host of Japanese acting awards for her outstanding performance — is just a marvel to watch. Memories of Matsuko is a fine choice to conclude Japan Society’s rather eclectic 2016 Globus Film Series “Japan Sings! The Japanese Musical Film.” As curator Michael Raine notes, “The ubiquity of music and song in postwar Japanese cinema became an anti-naturalist resource for modernist filmmakers to characterize social groups (Twilight Saloon,

We called Tetsuya Nakashima’s 2004 hit, Kamikaze Girls, the “otaku version of Jean-Pierre Jeunet’s Amelie,” referring to it as “fresh,” “frenetic,” “fast-paced,” and “very funny.” His feature-length follow-up, the stunningly gorgeous Memories of Matsuko, also recalls Amelie and all those other adjectives, albeit with much more sadness. Miki Nakatani (Ring, Silk) stars as Matsuko, a sweet woman who spent her life just looking to be loved but instead found nothing but heartbreak, deception, and physical and emotional abuse. But Memories of Matsuko, is not a depressing melodrama, even if Nakashima (Confessions, The World of Kanako) incorporates touches of Douglas Sirk every now and again. The film is drenched in glorious Technicolor, often breaking out into bright and cheerful musical numbers straight out of a 1950s fantasy world. As the movie begins, Matsuko has been found murdered, and her long-estranged brother (Akira Emoto) has sent his son, Sho (Eita), who never knew she existed, to clean out her apartment. As Sho goes through the mess she left behind, the film flashes back to critical moments in Matsuko’s life — and he also meets some crazy characters in the present. It’s difficult rooting for the endearing Matsuko knowing what becomes of her, but Nakashima’s remarkable visual style will grab you and never let go. And like Audrey Tatou in Amelie, Nakatani — who won a host of Japanese acting awards for her outstanding performance — is just a marvel to watch. Memories of Matsuko is a fine choice to conclude Japan Society’s rather eclectic 2016 Globus Film Series “Japan Sings! The Japanese Musical Film.” As curator Michael Raine notes, “The ubiquity of music and song in postwar Japanese cinema became an anti-naturalist resource for modernist filmmakers to characterize social groups (Twilight Saloon,