Film Forum is hosting a complete retrospective of the work of Yasujirō Ozu in honor of the 120th anniversary of his birth and 60th anniversary of his death

OZU 120: A COMPLETE RETROSPECTIVE

Film Forum

209 West Houston St.

June 9-29

212-727-8110

www.filmforum.org

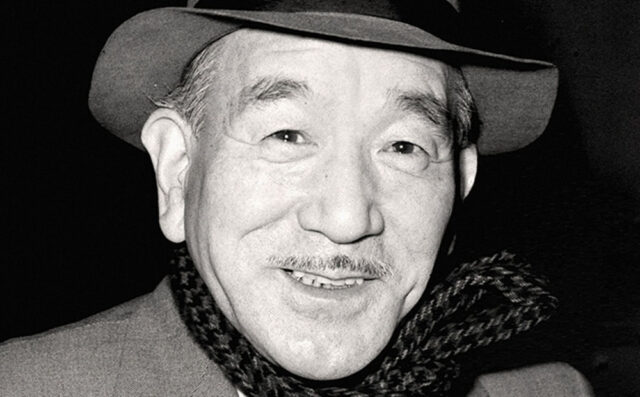

While it is never a bad time to celebrate the genius of Japanese auteur Yasujirō Ozu, now seems a particularly potent moment, with partisan politics and social media tearing friends and families apart, corporations gaining more and more power and wealth, and education under attack across America. From June 9 to 29, Film Forum is hosting “Ozu 120: A Complete Retrospective,” consisting of all three dozen of his extant works, in honor of the 120th anniversary of his birth, on December 12, 1903, and the 60th anniversary of his death on his birthday in 1963. It is no coincidence that six of the films have references to family members in their titles and another dozen involve youth and the passing of time over the course of a day and the seasons of the year.

The Tokyo-born writer, cameraman, and director made poignant “common people’s dramas,” known as shomin-geki, that penetrated deeply into the relationships among husbands and wives, children and parents, and bosses and employees, presenting honest portraits with care and intelligence. Interestingly, Ozu never married and never had kids of his own. His magnificent, meditative films feature long interior takes, little action, and few camera movements, letting the story unfold at its own pace, often photographed from low camera angles that came to be called tatami shots, from the point of view of someone kneeling on a tatami mat.

On June 19, the screenings of I Was Born, But . . . and a fragment of the short film A Straightforward Boy will be accompanied by live music by pianist and composer Makia Matsumura and a performance by master benshi Ichiro Kataoka. The June 20 showing of Tokyo Twilight will be introduced by Asian-American International Film Festival programming manager Kris Montello. Keep watching this space for more reviews of films from this must-see retrospective.

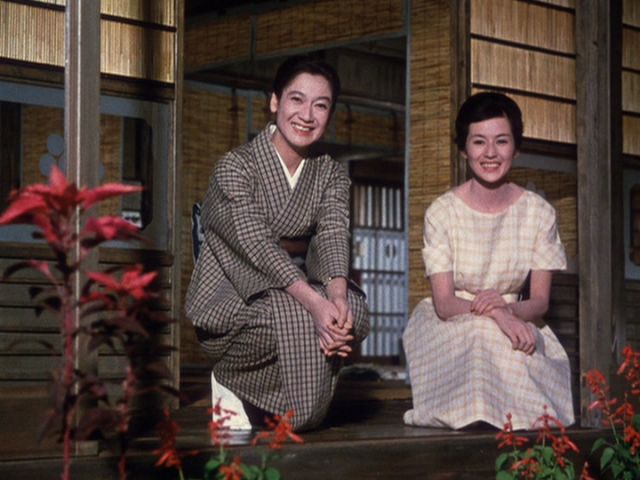

Father (Chishu Ryu) and daughter (Setsuko Hara) contemplate their future in Yasujirō Ozu masterpiece

LATE SPRING (BANSHUN) (Yasujirō Ozu, 1949)

Film Forum

June 9, 10, 11, 13, 28

filmforum.org

A masterpiece from start to finish, Yasujirō Ozu’s Late Spring marked a late spring of sorts in the Japanese auteur’s career as he moved into a new, post-WWII phase of his long exploration of Japanese family life and the middle class. Based on Kazuo Hirotsu’s novel Father and Daughter, the black-and-white film, written by Ozu with longtime collaborator Kogo Noda, tells the story of twenty-seven-year-old Noriko (Setsuko Hara), who lives at home with her widower father, Shukichi Somiya (Chishu Ryu), a university professor who has carved out a very simple existence for himself. Her aunt, Masa (Haruko Sugimura), thinks Noriko should get married, but she prefers caring for her father, who she believes would be lost without her. But when Somiya starts dropping hints that he might remarry, like his friend and colleague Jo Onodera (Masao Mishima) did — a deed that Noriko finds unbecoming and “filthy” — Noriko has to take another look at her future.

Late Spring is a monument of simplicity and economy while also being a complex, multilayered tale whose every moment offers unlimited rewards. From the placement and minimal movement of the camera to the design of the set to the carefully choreographed acting, Ozu infuses the work with meaning, examining not only the on-screen relationship between father and daughter but the intimate relationship between the film and the viewer. Ozu has a firm grasp on the state of the Japanese family as some of the characters try to hold on to old-fashioned culture and tradition while recovering from the war’s devastation and facing the modernism that is taking over.

Late Spring is part of month-long festival at Film Forum celebrating the work of director Yasujirō Ozu

Hara, who also starred as a character named Noriko in Ozu’s Early Summer and Tokyo Story, is magnificent as a young woman averse to change, forced to reconsider her supposed happy existence. And Ryu, who appeared in more than fifty Ozu films, is once again a model of restraint as the father, who only wants what is best for his daughter. Working within the censorship code of the Allied occupation and playing with narrative cinematic conventions of time and space, Ozu examines such dichotomies as marriage and divorce, the town and the city, parents and children, the changing roles of men and women in Japanese society, and the old and the young as postwar capitalism enters the picture, themes that are evident through much of his remarkable and unique oeuvre.

Takeshi Sakamato makes the first of many appearances as Kihachi in Yasujirō Ozu’s Passing Fancy

PASSING FANCY (DEKIGOKORO) (出来ごころ) (Yasujirō Ozu, 1933)

Film Forum

Sunday, June 11, 4:40

filmforum.org

Yasujirō Ozu might not have been keen on the latest technology — he made silent films until 1936, and his first color film was in 1958, near the end of his career — but there’s nothing old-fashioned about his mastery of camera and storytelling, as evidenced by one of his lesser-known comedy-dramas, Passing Fancy. Takeshi Sakamato stars as Kihachi, a character that would go on to appear in such other Ozu works as A Story of Floating Weeds, An Inn in Tokyo, and Record of a Tenement Gentleman. The film opens at a rōkyoku performance, where the audience is sitting on the floor on a hot day, mopping their brows and fanning themselves; Kihachi has an ever-present cloth on his head, looking clownish, a small boy with an injured eye who turns out to be his son, Tomio (Tokkankozo), sleeping by him. Foreshadowing Bresson-ian precision, Ozu and cinematographers Hideo Shigehara and Shojiro Sugimoto follow a small, lost change purse as several men inspect it, hoping to find money in it, then toss it away when it comes up empty. The scene establishes the pace and tone of the film, identifies Kihachi as the protagonist, and shows that there will be limited translated text and dialogue; in fact, Ozu never reveals what happened to Tomio’s eye. After the performance, Kihachi and his friend and coworker at the local brewery, Jiro (Den Obinata), meet a destitute young woman named Harue (Nobuko Fushimi). An intertitle explains, “Everyone years for love. Love sets our thoughts in flight.” Kihachi, a poor, single father, helps Harue get a place to stay and a job with restaurant owner Otome (Chouko Iida), hoping that Harue will become interested in him, but she instead takes a liking to the younger Jiro, who wants nothing to do with the whole situation, believing that Harue is using them.

The relationship between father (Takeshi Sakamato) and son (Tokkankozo) is at the heart of Passing Fancy

Ozu follows them all through their daily trials and tribulations — with hysterical comic bits, including how Tomio wakes up Kihachi and Jiro to make sure they’re not late for work — but things take a serious turn when the boy becomes seriously ill and Kihachi cannot afford to pay for the care he requires. Winner of the 1934 Japanese Kinema Junpo Award for Best Film — Ozu also won in 1933 for I Was Born, But . . . and 1935 for A Story of Floating Weeds — Passing Fancy is filled with gorgeous touches, as Ozu reveals the stark poverty in prewar Japan, focuses on class difference and illiteracy, and displays tender family relationships, all built around Kihachi’s impossible, very funny courtship of Harue and his bonding with Tomio, since love trumps all. And yes, that man on the boat is Chishū Ryū, who appeared in all but two of Ozu’s fifty-four films.

Wataru Hirayama (Shin Saburi) is a conflicted father-matchmaker in Yasujirō Ozu’s first color film, Equinox Flower

EQUINOX FLOWER (HIGANBANA) (Yasujirō Ozu, 1958)

Film Forum

June 14, 17, 18

filmforum.org

Yasujirō Ozu’s first film in color, at the studio’s request, is another engagingly told exploration of the changing relationship between parents and children, the traditional and the modern, in postwar Japan. Both funny and elegiac, Equinox Flower opens with businessman Wataru Hirayama (Shin Saburi) giving a surprisingly personal speech at a friend’s daughter’s wedding, explaining that he is envious that the newlyweds are truly in love, as opposed to his marriage, which was arranged for him and his wife, Kiyoko (Kinuyo Tanaka). Hirayama is later approached by an old middle school friend, Mikami (Ozu regular Chishu Ryu), who wants him to speak with his daughter, Fumiko (Yoshiko Kuga), who has left home to be with a man against her father’s will. Meanwhile, Yukiko (Fujiko Yamamoto), a friend of Hirayama’s elder daughter, Setsuko (Ineko Arima), is constantly being set up by her gossipy mother, Hatsu (Chieko Naniwa). Hirayama does not seem to be instantly against what Fumiko and Yukiko want for themselves, but when a young salaryman named Taniguchi (Keiji Sada) asks Hirayama for permission to marry his older daughter, Setsuko (Ineko Arima), Hirayama stands firmly against their wedding, claiming that he will decide Setsuko’s future. “Can’t I find my own happiness?” Setsuko cries out.

The widening gap between father and daughter represents the modernization Japan is experiencing, but the past is always close at hand; Ozu and longtime cowriter Kōgo Noda even have Taniguchi being transferred to Hiroshima, the scene of such tragedy and devastation. Yet there is still a lighthearted aspect to Equinox Flower, and Ozu and cinematographer Yuharu Atsuta embrace the use of color, including beautiful outdoor scenes of Hirayama and Kiyoko looking out across a river and mountain, a train station sign warning of dangerous winds, the flashing neon RCA Victor building, and laundry floating against a cloudy blue sky. The interiors are carefully designed as well, with objects of various colors arranged like still-life paintings, particularly a red teapot that shows up in numerous shots. And Kiyoko’s seemingly offhanded adjustment of a broom hanging on the wall is unforgettable. But at the center of it all is Saburi’s marvelously gentle performance as a proud man caught between the past, the present, and the future.

Ganjirō Nakamura is a sheer delight as the unpredictable patriarch of the Kohayagawa family in The End of Summer

THE END OF SUMMER (KOHAYAGAWA-KE NO AKI) (Yasujirō Ozu, 1961)

Film Forum

June 23, 24, 27

www.filmforum.org

Yasujirō Ozu’s next-to-last film, 1961’s The End of Summer, is a poignant examination of growing old in a changing Japan; Ozu would make only one more film, 1962’s An Autumn Afternoon, before passing away on his sixtieth birthday in December 1963. Ganjirō Nakamura is absolutely endearing as Manbei Kohayagawa, the family patriarch who heads a small sake brewery. The aging grandfather has been mysteriously disappearing for periods of time, secretly visiting his old girlfriend, Sasaki (Chieko Naniwa), and her daughter, Yuriko (Reiko Dan), who might or might not be his. In the meantime, Manbei’s brother-in-law, Kitagawa (Daisuke Katō), is trying to set up Manbei’s widowed daughter-in-law, Akiko (Setsuko Hara), with businessman Isomura Eiichirou (Hisaya Morishige), while also attempting to find a proper suitor for Manbei’s youngest daughter, Noriko (Yoko Tsukasa), a typist with strong feelings for a coworker who has moved to Sapporo. Manbei’s other daughter, Fumiko (Michiyo Aratama), is married to Hisao (Keiju Kobayashi), who works at the brewery and is concerned about Manbei’s suddenly unpredictable behavior. When Manbei suffers a heart attack, everyone is forced to look at their own lives, both personal and professional, as the single women consider their suitors and the men contemplate the future of the business, which might involve selling out to a larger company. “The Kohayagawa family is complicated indeed,” Hisao’s colleague tells him when trying to figure out who’s who, an inside joke about the complex relationships developed by Ozu and longtime cowriter Kôgo Noda in the film as well as in the casting.

Akiko (Setsuko Hara) and Noriko (Yoko Tsukasa) represent old and new Japan in Ozu’s penultimate film

The End of Summer tells a far more serious story than Late Spring and many other Ozu films that deal with matchmaking and middle-class Japanese life, both pre- and postwar. The perpetually smiling Hara, who played unrelated women named Noriko in three previous Ozu films, once again plays a young widow named Akiko here, as she did in Late Autumn, while Tsukasa, who played Hara’s daughter in Late Autumn, now takes over the name of Noriko as Akiko’s sister. Late Autumn also featured a character named Yuriko Sasaki, played by Mariko Okada, who went on to play a woman named Akiko in Ozu’s final film, An Autumn Afternoon. Got that? Ozu’s fifth film in color, The End of Summer uses several beautiful establishing shots that incorporate flashing light and bold hues — including a neon sign that declares “New Japan” — photographed by Asakazu Nakai (Seven Samurai, Throne of Blood, Ran), as well as numerous carefully designed set pieces that place the old and the new in direct contrast, primarily when Akiko and Noriko are alone, the former in a kimono, the latter in more modern dress. But at the center of it all is Nakamura, who plays Manbei with a childlike glee, as if Ozu is equating birth and death, the beginning and the end.

LATE AUTUMN (AKIBIYORI) (Yasujirō Ozu, 1960)

Film Forum

June 23, 24, 28

filmforum.org

Yasujirō Ozu revisits one of his greatest triumphs, 1949’s Late Spring, in the 1960 drama Late Autumn, the Japanese auteur’s fourth color film and his third-to-last work. Whereas the black-and-white Late Spring is about a widowed father (Chishu Ryu) and his unmarried adult daughter (Setsuko Hara) contemplating their futures, Late Autumn deals with young widow Akiko Miwa (Hara again) and her daughter, Ayako (Yoku Tsukasa). At a ceremony honoring the seventh anniversary of Mr. Miwa’s death, several of his old friends gather together and are soon plotting to marry off both the younger Akiko, whom they all had crushes on, and twenty-four-year-old Ayako. The three businessmen — Soichi Mamiya (Shin Saburi), Shuzo Taguchi (Nobuo Nakamura), and Seiichiro Hirayama (Ryuji Kita) — serve as a kind of comedic Greek chorus, matchmaking and arguing like a trio of yentas, while Akiko and Ayako maintain creepy smiles as the men lay out their misguided, unwelcome plans.

Mamiya makes numerous attempts to fix Ayako up with one of his employees, Shotaru Goto (Keiji Sada), but Ayako wants none of it, preferring the freedom and independence displayed by her best friend, Yoko (Yuriko Tashiro), who represents the new generation in Japan. At the same time, their matchmaking for Akiko borders on the slapstick. Based on a story by Ton Satomi, Late Autumn, written by Ozu with longtime collaborator Kôgo Noda, is a relatively lighthearted film from the master, with sly jokes and playful references while examining a Japan that is in the midst of significant societal change in the postwar era. Kojun Saitô’s Hollywood-esque score is often bombastically melodramatic, but Yuuharu Atsuta’s cinematography keeps things well grounded with Ozu’s trademark low-angle, unmoving shots amid carefully designed interior sets.

Some stories are just too big to be told in one film, let alone two, so from April 19 to May 16, Film Forum is showing well-known and under-the-radar official and unofficial trilogies, including three-packs from Francis Ford Coppola, Sergio Leone, Lucas Belvaux, Andrzej Wajda, Jean Cocteau, Ingmar Bergman, Nicolas Winding Refn, and Satyajit Ray, among others. (Note: There is separate admission to each film.) Masako Kobayashi’s ten-hour epic, The Human Condition, based on a popular novel by Jumpei Gomikawa, is one of the most stunning achievements ever captured on film. Shot over the course of three years, the film follows one man’s harrowing struggle to never give up his humanity as he is dragged deeper and deeper into the morass of WWII. Tatsuya Nakadai is remarkable as Kaji, a man who believes in common decency, personal discipline, and, above all else, that humanity will always triumph. In the first part, No Greater Love, the steadfastly practical Kaji is hesitant to marry his sweetheart, Michiko (Michiyo Aratama), for fear that he will be called to serve in the Japanese army and might not come back to her alive. But when his detailed plan to treat workers fairly is accepted by the government, he is made labor supervisor of a mine in far-off Southern Manchuria, where hundreds of Chinese prisoners are brought in as well — and regularly starved, beaten, and, on occasion, brutally killed in cold blood. Kaji’s methods, which have close ties to communism, leading many to refer to him as a “Red,” anger both sides — the Japanese want to treat the workers like animals, and the Chinese prisoners don’t trust that he has their welfare in mind. A series of escape attempts threatens the stability of the labor camp and comes between Kaji and Michiko, whose undying love is echoed in the yearning, unfulfilled desire between a Korean prisoner and a Japanese prostitute. Broken promises, lies, and betrayal reach a tense conclusion that sets the stage for the second part of Kobayashi’s masterpiece.

Some stories are just too big to be told in one film, let alone two, so from April 19 to May 16, Film Forum is showing well-known and under-the-radar official and unofficial trilogies, including three-packs from Francis Ford Coppola, Sergio Leone, Lucas Belvaux, Andrzej Wajda, Jean Cocteau, Ingmar Bergman, Nicolas Winding Refn, and Satyajit Ray, among others. (Note: There is separate admission to each film.) Masako Kobayashi’s ten-hour epic, The Human Condition, based on a popular novel by Jumpei Gomikawa, is one of the most stunning achievements ever captured on film. Shot over the course of three years, the film follows one man’s harrowing struggle to never give up his humanity as he is dragged deeper and deeper into the morass of WWII. Tatsuya Nakadai is remarkable as Kaji, a man who believes in common decency, personal discipline, and, above all else, that humanity will always triumph. In the first part, No Greater Love, the steadfastly practical Kaji is hesitant to marry his sweetheart, Michiko (Michiyo Aratama), for fear that he will be called to serve in the Japanese army and might not come back to her alive. But when his detailed plan to treat workers fairly is accepted by the government, he is made labor supervisor of a mine in far-off Southern Manchuria, where hundreds of Chinese prisoners are brought in as well — and regularly starved, beaten, and, on occasion, brutally killed in cold blood. Kaji’s methods, which have close ties to communism, leading many to refer to him as a “Red,” anger both sides — the Japanese want to treat the workers like animals, and the Chinese prisoners don’t trust that he has their welfare in mind. A series of escape attempts threatens the stability of the labor camp and comes between Kaji and Michiko, whose undying love is echoed in the yearning, unfulfilled desire between a Korean prisoner and a Japanese prostitute. Broken promises, lies, and betrayal reach a tense conclusion that sets the stage for the second part of Kobayashi’s masterpiece.

Japan Society’s Monthly Classics series continues February 5 with the story of one of the screen’s most brutal antiheroes, a samurai you can’t help but root for despite his coldhearted brutality, a heartless killer called “a man from hell.” Based on Kaizan Nakazato’s forty-one-volume serial novel Dai-bosatsu Tōge, Kihachi Okamoto’s The Sword of Doom, aka The Great Bodhisattva Pass, begins in 1860 with Ryunosuke Tsukue (Tatsuya Nakadai) slaying an elderly Buddhist pilgrim (Ko Nishimura) apparently for no reason as the man visits a far-off mountain grave. Shortly before Ryunosuke is to battle Bunnojo Utsuki (Ichiro Nakaya) in a competition using unsharpened wooden swords, the man’s wife, Ohama (Michiyo Aratama), comes to him, begging for Ryunosuke to lose the match on purpose to save her family’s future. A master swordsman with an unorthodox style, Ryunosuke takes advantage of the situation in more ways than one. As emotionless as he is fearless, Ryunosuke is soon ambushed on a forest road, but killing, to him, comes natural, whether facing one man or dozens — or even hundreds. The only person he shows even the slightest respect for is Toranosuke Shimada (Toshirō Mifune), the instructor at a sword-fighting school. “We have rules concerning strangers,” Toranosuke tells him, but Ryunosuke plays by no rules. “The sword is the soul. Study the soul to know the sword. Evil mind, evil sword,” Toranosuke adds, words that torment Ryunosuke, who tries to start a family in spite of his hard, detached demeanor. But regardless of circumstance, Ryunosuke continues on his bloody path, culminating in an unforgettable battle that is one of the finest of the jidaigeki genre.

Japan Society’s Monthly Classics series continues February 5 with the story of one of the screen’s most brutal antiheroes, a samurai you can’t help but root for despite his coldhearted brutality, a heartless killer called “a man from hell.” Based on Kaizan Nakazato’s forty-one-volume serial novel Dai-bosatsu Tōge, Kihachi Okamoto’s The Sword of Doom, aka The Great Bodhisattva Pass, begins in 1860 with Ryunosuke Tsukue (Tatsuya Nakadai) slaying an elderly Buddhist pilgrim (Ko Nishimura) apparently for no reason as the man visits a far-off mountain grave. Shortly before Ryunosuke is to battle Bunnojo Utsuki (Ichiro Nakaya) in a competition using unsharpened wooden swords, the man’s wife, Ohama (Michiyo Aratama), comes to him, begging for Ryunosuke to lose the match on purpose to save her family’s future. A master swordsman with an unorthodox style, Ryunosuke takes advantage of the situation in more ways than one. As emotionless as he is fearless, Ryunosuke is soon ambushed on a forest road, but killing, to him, comes natural, whether facing one man or dozens — or even hundreds. The only person he shows even the slightest respect for is Toranosuke Shimada (Toshirō Mifune), the instructor at a sword-fighting school. “We have rules concerning strangers,” Toranosuke tells him, but Ryunosuke plays by no rules. “The sword is the soul. Study the soul to know the sword. Evil mind, evil sword,” Toranosuke adds, words that torment Ryunosuke, who tries to start a family in spite of his hard, detached demeanor. But regardless of circumstance, Ryunosuke continues on his bloody path, culminating in an unforgettable battle that is one of the finest of the jidaigeki genre.