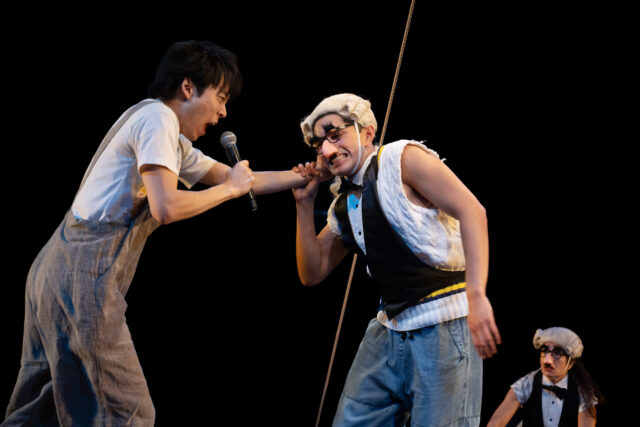

Steve Carell did not receive a Tony nod for his Broadway debut in Uncle Vanya (photo by Marc J. Franklin)

UNCLE VANYA

Vivian Beaumont Theater at Lincoln Center Theater

150 West 65th St. between Broadway & Amsterdam Ave.

Tuesday – Saturday through June 16, $104-$348

212-362-7600

www.lct.org

PATRIOTS

Ethel Barrymore Theatre

243 West Forty-Seventh St. between Broadway & Eighth Ave.

Tuesday – Sunday through June 23, $49–$294

patriotsbroadway.com

When the 2024 Tony nominations were announced on April 30, there were several notable names missing, particularly that of Steve Carell. The Massachusetts-born Carell, sixty-one, is currently finishing up his Broadway debut as the title character in Heidi Schreck’s muddled new translation of Anton Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya, running at the Vivian Beaumont through June 16. The show received a single nomination, for Carell’s costar William Jackson Harper as Best Actor in a Play, for his portrayal of Dr. Astrov; Schreck and director Lila Neugebauer focus so much on the doctor that the play ought to be renamed Dr. Astrov.

Carell, who cut his comic chops at Second City in Chicago and on The Daily Show with Jon Stewart, has been nominated for an Emmy eleven times for his role as Michael Scott on The Office, and he received a Best Actor Oscar nod for his portrayal of the real-life multimillionaire and murderer John Eleuthère du Pont in Foxcatcher. Carell has also appeared in such films and television series as The 40-Year-Old Virgin, Little Miss Sunshine, The Big Short, and The Morning Show as well as the very dark limited series The Patient.

One name that might have been a surprise was that of Michael Stuhlbarg. The California-born Stuhlbarg, fifty-five, is currently finishing up his role as the real-life Russian oligarch Boris Berezovsky in Peter Morgan’s bumpy but ultimately satisfying Patriots, running at the Ethel Barrymore through June 23. The nomination was the only one for the play, which is directed by Rupert Goold.

All five of the nominees are known for their work on television; in addition to theater veteran Harper, who played Danny Rebus on the reboot of The Electric Company and Chidi Anagonye on The Good Place, the nominees include Emmy winner Jeremy Strong of Succession for An Enemy of the People, nine-time Emmy nominee and Tony winner Liev Schreiber of Ray Donovan for Doubt: A Parable, and Tony and Grammy winner and Emmy and Oscar nominee Leslie Odom Jr. of Smash for Purlie Victorious (A Non-Confederate Romp through the Cotton Patch).

A two-time Emmy and Tony nominee and Obie and Drama Desk winner, Stuhlbarg has appeared in such films as A Serious Man, Call Me by Your Name, and The Shape of Water; has portrayed such villains on TV as Arnold Rothstein in Boardwalk Empire, Jimmy Baxter in Your Honor, and Richard Sackler in Dopesick; and has seven Shakespeare plays on his resume in addition to Cabaret, The Pillowman, and The Invention of Love on Broadway.

Michael Stuhlbarg received his second Tony nomination for his role as Boris Berezovsky in Patriots (photo by Matthew Murphy)

Uncle Vanya and Patriots are both set in Russia after the fall of the Berlin Wall, around the time of Mikhail Gorbachev’s perestroika program, although the exact time of Schreck’s narrative is never specifically stated. Vanya has sacrificed happiness in order to manage the family estate with Sonia (Alison Pill), his niece. When professor Alexander (Alfred Molina) — who was married to Vanya’s late sister, Sonia’s mother — and his younger, sexy wife Elena (Anika Noni Rose), arrive at the estate with plans to sell it, Vanya, who is in love with Elena and is not a terrific businessman, is forced to take stock of his life, and he doesn’t like what he sees.

Boris of Patriots is a stark contrast: He seeks out the many pleasures the world has to offer, determined, since childhood, to be a success with power and influence, unconcerned with the bodies he leaves in his wake. Cutting a deal with Alexander Stalyevich Voloshin (Jeff Biehl), Boris assures the politician that he is going to be a rich man. “No good being rich if I’m dead,” Voloshin says, to which Boris responds, “It’s always good being rich.” Boris believes he is in control of Russia when he chooses to groom a minor functionary as president, intending to make him his puppet, but the man, Vladimir Putin (Will Keen), ultimately has other ideas and soon becomes Boris’s hated enemy.

Carell hovers in the background of Uncle Vanya, giving the stage over to the other characters, similar to how Vanya has surrendered taking action in his life. He often sits and mopes on a couch in the back, fading into the shadows; even when he pulls out a gun, he is too meek and mild. For the play to work, the audience needs to connect emotionally with Vanya, but Carell can’t quite carry off the key moments.

Stuhlbarg leaps across Miriam Buether’s multilevel stage with boundless energy in Patriots as Boris battles Putin over the heart and soul of Russia. Boris has no fear, until he realizes that Putin is a lot more than he ever bargained for. “I will make sure the Russian people learn to love our little puppet,” Boris says, but it’s too late. “The fact is I am president,” Putin declares. Boris responds, “And I put you there!!!!!” To which Putin replies, “That’s opinion. Not fact.”

Carell may be more of a household name than Stuhlbarg, but the latter gained notoriety when, on March 31, a homeless man struck him with a rock near Central Park, and Stuhlbarg, much like Boris most likely would have done, chased after him until the police caught up with the attacker outside of the Russian consulate on East Ninety-First. The consulate was a fitting location for the two-time Tony nominee.

[Mark Rifkin is a Brooklyn-born, Manhattan-based writer and editor; you can follow him on Substack here.]