Ralph Bakshi’s animated Fritz the Cat is part of Quad tribute to X-rated cinema

Quad Cinema

34 West 13th St. between Fifth & Sixth Aves.

Series runs December 14 – January 10

212-255-2243

quadcinema.com

In 1974, the promotional tag line for the porn sequel Emmanuelle II was “X was never like this.” While that film flaunted it, more mainstream movies treat the rating as a plague that could kill distribution and box office. The Quad is paying tribute to the controversial grade with “Rated X,” consisting of thirty-four films screening December 14 to January 10 that were either X-rated or had to make a few nips and tucks in order to avoid that tag. The films range from Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange and John Schlesinger’s Midnight Cowboy to George A. Romero’s Dawn of the Dead and Tobe Hooper’s The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, from Marco Bellocchio’s Devil in the Flesh and Pedro Almodóvar’s Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down! to Vilgot Sjöman’s I Am Curious (Yellow) and Nagisa Oshima’s In the Realm of the Senses. Keep watching this space for additional reviews of this, um, titillating film fest.

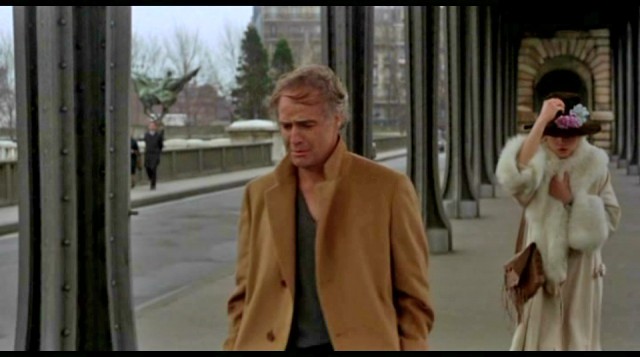

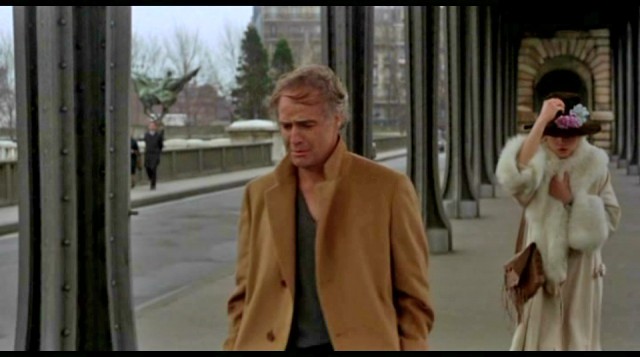

Marlon Brando and Maria Schneider star in Bernardo Bertolucci’s controversial Last Tango in Paris

LAST TANGO IN PARIS (ULTIMO TANGO A PARIGI) (Bernardo Bertolucci, 1972)

Saturday, December 15, 7.40

Sunday, December 16, 7:20

Friday, December 28, 8:35

Saturday, January 5, 8:55

www.fiaf.org

One of the most artistic films ever made about seduction, Bernardo Bertolucci’s controversial X-rated Last Tango in Paris is part of the Quad’s “Paris Stripped Bare” and “Pictures from the Revolution: Bertolucci’s Italian Period” series in addition to “Rated X.” Written by Bertolucci (The Conformist, The Spider’s Stratagem), who passed away in Rome in November at the age of seventy-seven, with regular collaborator and editor Franco Arcalli and with French dialogue by Agnès Varda (Le Bonheur, Vagabond), the film opens with credits featuring jazzy romantic music by Argentine saxophonist Gato Barbieri and two colorful and dramatic paintings by Francis Bacon, “Double Portrait of Lucian Freud and Frank Auerbach” and “Study for a Portrait,” that set the stage for what is to follow. (Bacon was a major influence on the look and feel of the film, photographed by Vittorio Storaro.) Bertolucci then cuts to a haggard man (Marlon Brando) standing under the Pont de Bir-Hakeim in Paris, screaming out, “Fucking God!” His hair disheveled, he is wearing a long brown jacket and seems to be holding back tears. An adorable young woman (Maria Schneider) in a fashionable fluffy white coat and black hat with flowers passes by, stops and looks at him, then moves on. They meet again inside a large, sparsely furnished apartment at the end of Rue Jules Verne that they are each interested in renting. Both looking for something else in life, they quickly have sex and roll over on the floor, exhausted. For the next three days, they meet in the apartment for heated passion that the man, Paul, insists include nothing of the outside world — no references to names or places, no past, no present, no future; the young woman, Jeanne, agrees. Their sex goes from gentle and touching to brutal and animalistic; in fact, after one session, Bertolucci cuts to actual animals. The film is nothing if not subtle.

One of the most artistic films ever made about seduction, Bernardo Bertolucci’s controversial X-rated Last Tango in Paris is part of the Quad’s “Paris Stripped Bare” and “Pictures from the Revolution: Bertolucci’s Italian Period” series in addition to “Rated X.” Written by Bertolucci (The Conformist, The Spider’s Stratagem), who passed away in Rome in November at the age of seventy-seven, with regular collaborator and editor Franco Arcalli and with French dialogue by Agnès Varda (Le Bonheur, Vagabond), the film opens with credits featuring jazzy romantic music by Argentine saxophonist Gato Barbieri and two colorful and dramatic paintings by Francis Bacon, “Double Portrait of Lucian Freud and Frank Auerbach” and “Study for a Portrait,” that set the stage for what is to follow. (Bacon was a major influence on the look and feel of the film, photographed by Vittorio Storaro.) Bertolucci then cuts to a haggard man (Marlon Brando) standing under the Pont de Bir-Hakeim in Paris, screaming out, “Fucking God!” His hair disheveled, he is wearing a long brown jacket and seems to be holding back tears. An adorable young woman (Maria Schneider) in a fashionable fluffy white coat and black hat with flowers passes by, stops and looks at him, then moves on. They meet again inside a large, sparsely furnished apartment at the end of Rue Jules Verne that they are each interested in renting. Both looking for something else in life, they quickly have sex and roll over on the floor, exhausted. For the next three days, they meet in the apartment for heated passion that the man, Paul, insists include nothing of the outside world — no references to names or places, no past, no present, no future; the young woman, Jeanne, agrees. Their sex goes from gentle and touching to brutal and animalistic; in fact, after one session, Bertolucci cuts to actual animals. The film is nothing if not subtle.

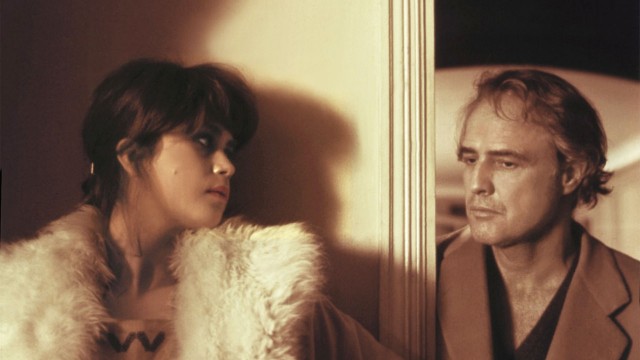

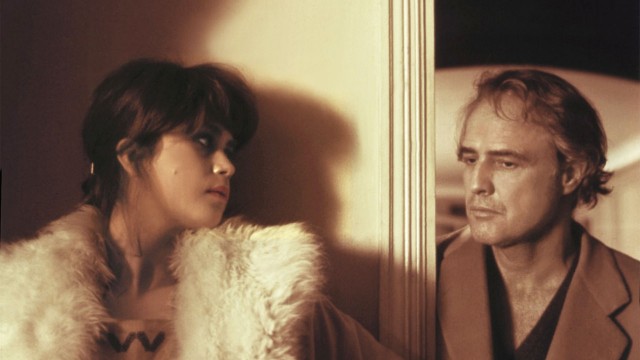

Jeanne (Maria Schneider) and Paul (Marlon Brando) share a private, sexual relationship in Last Tango in Paris

The lovers’ real lives are revealed in bits and pieces, as Paul tries to recover from his wife’s suicide and Jeanne deals with a fiancée, Thomas (Jean-Pierre Léaud), who has suddenly decided to make a film about them, without her permission, asking precisely the kind of questions that Paul never wants to talk about. When away from the apartment, Jeanne is shown primarily in the bright outdoors, flitting about fancifully and giving Thomas a hard time; in one of the only scenes in which she’s inside, Thomas makes a point of opening up several doors, preventing her from ever feeling trapped. Meanwhile, Paul is seen mostly in tight, dark spaces, especially right after having a fight with his dead wife’s mother. He walks into his hotel’s dark hallway, the only light coming from two of his neighbors as they open their doors just a bit to spy on him. Not saying anything, he pulls their doors shut as the screen goes from light to dark to light to dark again, and then Bertolucci cuts to Paul and Jeanne’s apartment door as she opens it, ushering in the brightness that always surrounds her. It’s a powerful moment that heightens the difference between the older, less hopeful man and the younger, eager woman. Inevitably, however, the safety of their private, primal relationship is threatened, and tragedy awaits.

Jeanne and Paul develop a complicated sexual relationship in Last Tango

“I’ve tried to describe the impact of a film that has made the strongest impression on me in almost twenty years of reviewing. This is a movie people will be arguing about, I think, for as long as there are movies,” Pauline Kael wrote in the New Yorker on October 28, 1972, shortly before Last Tango closed the tenth New York Film Festival. “It is a movie you can’t get out of your system, and I think it will make some people very angry and disgust others. I don’t believe that there’s anyone whose feelings can be totally resolved about the sex scenes and the social attitudes in this film.” More than forty years later, the fetishistic Last Tango in Paris still has the ability to evoke those strong emotions. The sex scenes range from tender, as when Jeanne tells Paul they should try to climax without touching, to when Paul uses butter in an attack that was not scripted and about which Schneider told the Daily Mail in 2007, “I felt humiliated and to be honest, I felt a little raped, both by Marlon and by Bertolucci. After the scene, Marlon didn’t console me or apologise. Thankfully, there was just one take.” At the time of the shooting, Brando was forty-eight and Schneider nineteen; Last Tango was released between The Godfather and Missouri Breaks, in which Brando starred with Jack Nicholson, while Schneider would go on to make Michelangelo Antonioni’s The Passenger with Nicholson in 1975. Brando died in 2004 at the age of eighty, leaving behind a legacy of more than forty films. Schneider died in 2011 at the age of fifty-eight; she also appeared in more than forty films, but she was never able to escape the associations that followed her after her breakthrough performance in Last Tango, which featured extensive nudity, something she refused to do ever again. Even in 2018, Last Tango in Paris is both sexy and shocking, passionate and provocative, alluring and disturbing, all at the same time, a movie that, as Kael said, viewers won’t easily be able to get out of their system.

Peggy Gravel’s quaint suburban life is about to go to hell in John Waters’s Desperate Living

DESPERATE LIVING (John Waters, 1977)

Friday, December 21, 8:35

Wednesday, December 26, 8:35

Wednesday, January 2, 8:35

quadcinema.com

A turning point in his career, John Waters’s Desperate Living is an off-the-charts bizarre, fetishistic fairy tale, the ultimate suburban nightmare. Mink Stole stars as Peggy Gravel, a wealthy housewife suffering yet another of her mental breakdowns. In the heat of the moment, she and the family maid, four-hundred-pound Grizelda Brown (Jean Hill), kill Peggy’s mild-mannered husband, Bosley (George Stover), and the two women end up finding refuge in one of the weirdest towns ever put on celluloid, Mortville, where MGM’s The Wizard of Oz and Babes in Toyland meet Russ Meyer’s Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill! (with some Kenneth Anger, Jack Smith, and Douglas Sirk thrown into the mix as well). “I ain’t your maid anymore, bitch! I’m your sister in crime!” Grizelda declares. Peggy and Grizelda move into the “guest house” of manly Mole McHenry (Susan Lowe) and her blonde bombshell lover, Muffy St. Jacques (Liz Renay). Mortville is run as a kind of fascist state by the cruel and unusual despot Queen Carlotta (Edith Massey), an evil shrew who enjoys being serviced by her men-in-leather attendants, issues psychotic proclamations, and is determined that her daughter, Princess Coo-Coo (Mary Vivian Pearce), stop dating her garbage-man boyfriend, Herbert (George Figgs). (Wait, Mortville has a sanitation department?) Camp and trash combine like nuclear fission as things get only crazier from there, devolving into gorgeous low-budget madness and completely over-the-top ridiculousness, a mélange of sex, violence, and impossible-to-describe lunacy that Waters himself claimed was a movie “for fucked-up children.”

A turning point in his career, John Waters’s Desperate Living is an off-the-charts bizarre, fetishistic fairy tale, the ultimate suburban nightmare. Mink Stole stars as Peggy Gravel, a wealthy housewife suffering yet another of her mental breakdowns. In the heat of the moment, she and the family maid, four-hundred-pound Grizelda Brown (Jean Hill), kill Peggy’s mild-mannered husband, Bosley (George Stover), and the two women end up finding refuge in one of the weirdest towns ever put on celluloid, Mortville, where MGM’s The Wizard of Oz and Babes in Toyland meet Russ Meyer’s Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill! (with some Kenneth Anger, Jack Smith, and Douglas Sirk thrown into the mix as well). “I ain’t your maid anymore, bitch! I’m your sister in crime!” Grizelda declares. Peggy and Grizelda move into the “guest house” of manly Mole McHenry (Susan Lowe) and her blonde bombshell lover, Muffy St. Jacques (Liz Renay). Mortville is run as a kind of fascist state by the cruel and unusual despot Queen Carlotta (Edith Massey), an evil shrew who enjoys being serviced by her men-in-leather attendants, issues psychotic proclamations, and is determined that her daughter, Princess Coo-Coo (Mary Vivian Pearce), stop dating her garbage-man boyfriend, Herbert (George Figgs). (Wait, Mortville has a sanitation department?) Camp and trash combine like nuclear fission as things get only crazier from there, devolving into gorgeous low-budget madness and completely over-the-top ridiculousness, a mélange of sex, violence, and impossible-to-describe lunacy that Waters himself claimed was a movie “for fucked-up children.”

John Waters’s Desperate Living is a celebration of camp and trash, an extremely adult and bizarre fairy tale

The opening scenes of Peggy’s meltdown are utterly hysterical. When a neighbor hits a baseball through her bedroom window and offers to pay for it with his allowance, she screams, “How about my life? Do you get enough allowance to pay for that? I know you were trying to kill me! What’s the matter with the courts? Do they allow this lawlessness and malicious destruction of property to run rampant? I hate the Supreme Court! Oh, God. God. God. Go home to your mother! Doesn’t she ever watch you? Tell her this isn’t some communist day-care center! Tell your mother I hate her! Tell your mother I hate you!” The sets and costumes are deranged — and perhaps influenced Pee-wee’s Playhouse — the relatively spare score is fun, and the acting is, well, appropriate. The first half of the film is better than the second half, but it’s still a delight to watch Waters, who wrote, directed, and produced the film, which was shot in a kind of lurid Technicolor by Charles Ruggero, take on authority figures (beware of Sheriff Shitface), gender identity, class structure, hero worship, beauty, race, crime, nudity, and, of course, at its very heart, love and romance.

Michael Rooker stars as a troubled murderer in Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer

HENRY: PORTRAIT OF A SERIAL KILLER (John McNaughton, 1986)

Thursday, December 27, 6:45

Saturday, January 5, 1.00

quadcinema.com

More than thirty years ago, when director John McNaughton (Mad Dog and Glory, Wild Things) was asked by executive producers Malik B. and Waleed B. Ali to make a low-budget horror film, he and cowriter Richard Fire decided to base their tale on the exploits of serial killer Henry Lee Lucas, whose story McNaughton had just seen on 20/20. The result was this creepy, dark, well-paced effort starring Michael Rooker as Henry, a brooding, casual serial killer who can’t quite remember how he murdered his mother. Henry lives in suburban Chicago with ex-con Otis (Tom Towles), whose sexy young sister, Becky (Tracy Arnold), comes to stay with them to get away from her abusive husband. As the relationship among the three of them grows more and more complicated, Henry continues to kill people — and get away with it. The opening tableau of some of Henry’s murder victims — the actual killings aren’t shown in the beginning — is beautifully done, although it also fetishizes violence against women, which is extremely disturbing. (Several of the victims are played by the same woman, Mary Demas, in different wigs.) Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer, which was not released until 1989 because of its graphic content, was nominated for six Independent Spirit Awards in 1990, and Rooker was named Best Actor at the Seattle International Film Festival.

More than thirty years ago, when director John McNaughton (Mad Dog and Glory, Wild Things) was asked by executive producers Malik B. and Waleed B. Ali to make a low-budget horror film, he and cowriter Richard Fire decided to base their tale on the exploits of serial killer Henry Lee Lucas, whose story McNaughton had just seen on 20/20. The result was this creepy, dark, well-paced effort starring Michael Rooker as Henry, a brooding, casual serial killer who can’t quite remember how he murdered his mother. Henry lives in suburban Chicago with ex-con Otis (Tom Towles), whose sexy young sister, Becky (Tracy Arnold), comes to stay with them to get away from her abusive husband. As the relationship among the three of them grows more and more complicated, Henry continues to kill people — and get away with it. The opening tableau of some of Henry’s murder victims — the actual killings aren’t shown in the beginning — is beautifully done, although it also fetishizes violence against women, which is extremely disturbing. (Several of the victims are played by the same woman, Mary Demas, in different wigs.) Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer, which was not released until 1989 because of its graphic content, was nominated for six Independent Spirit Awards in 1990, and Rooker was named Best Actor at the Seattle International Film Festival.

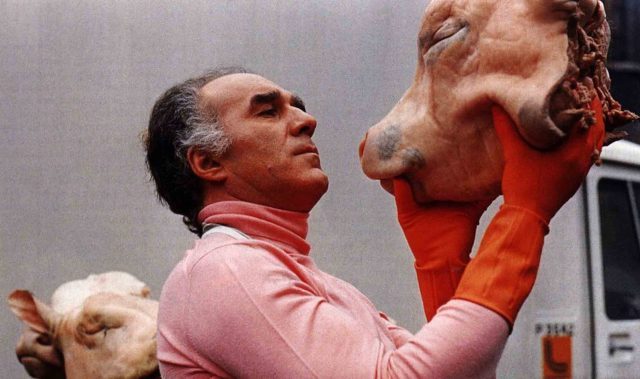

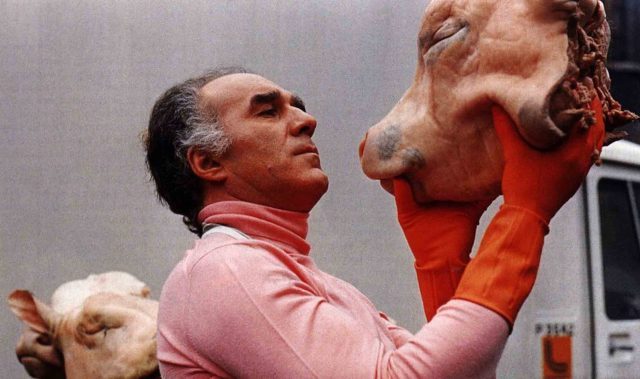

Michel Piccoli prepares to make a pig of himself in La Grande Bouffe

LA GRANDE BOUFFE (THE BIG FEAST) (BLOW-OUT) (Marco Ferreri, 1973)

Tuesday, January 1, 5:30

Friday, January 4, 9:15

quadcinema.com

Fed up with their lives, four old friends decide to literally eat themselves to death in one last grand blow-out. Cowritten and directed by Marco Ferreri (Chiedo asilo, La casa del sorriso), La Grande Bouffe features a cast that is an assured recipe for success, bringing together a quartet of legendary actors, all playing characters with their real first names: Marcello Mastroianni as sex-crazed airplane pilot Marcello, Philippe Noiret as mama’s boy and judge Philippe, Michel Piccoli as effete television host Michel, and Ugo Tognazzi as master gourmet chef Ugo. They move into Philippe’s hidden-away family villa, where they plan to eat and screw themselves to death, with the help of a group of prostitutes led by Andréa (Andréa Ferréol). Gluttons for punishment, the four men start out having a gas, but as the feeding frenzy continues, so does the flatulence level, and the men start dropping one by one. While the film, which won the FIPRESCI Prize at the 1973 Cannes Film Festival, might not be quite the grand feast it sets out to be, it still is one very tasty meal. Just be thankful that it’s not shown in Odoroma. Bon appetit!

Fed up with their lives, four old friends decide to literally eat themselves to death in one last grand blow-out. Cowritten and directed by Marco Ferreri (Chiedo asilo, La casa del sorriso), La Grande Bouffe features a cast that is an assured recipe for success, bringing together a quartet of legendary actors, all playing characters with their real first names: Marcello Mastroianni as sex-crazed airplane pilot Marcello, Philippe Noiret as mama’s boy and judge Philippe, Michel Piccoli as effete television host Michel, and Ugo Tognazzi as master gourmet chef Ugo. They move into Philippe’s hidden-away family villa, where they plan to eat and screw themselves to death, with the help of a group of prostitutes led by Andréa (Andréa Ferréol). Gluttons for punishment, the four men start out having a gas, but as the feeding frenzy continues, so does the flatulence level, and the men start dropping one by one. While the film, which won the FIPRESCI Prize at the 1973 Cannes Film Festival, might not be quite the grand feast it sets out to be, it still is one very tasty meal. Just be thankful that it’s not shown in Odoroma. Bon appetit!

One of the most artistic films ever made about seduction, Bernardo Bertolucci’s controversial X-rated Last Tango in Paris is part of the Quad’s “Paris Stripped Bare” and “Pictures from the Revolution: Bertolucci’s Italian Period” series in addition to “Rated X.” Written by Bertolucci (The Conformist, The Spider’s Stratagem), who passed away in Rome in November at the age of seventy-seven, with regular collaborator and editor Franco Arcalli and with French dialogue by Agnès Varda (Le Bonheur, Vagabond), the film opens with credits featuring jazzy romantic music by Argentine saxophonist Gato Barbieri and two colorful and dramatic paintings by Francis Bacon, “Double Portrait of Lucian Freud and Frank Auerbach” and “Study for a Portrait,” that set the stage for what is to follow. (Bacon was a major influence on the look and feel of the film, photographed by Vittorio Storaro.) Bertolucci then cuts to a haggard man (Marlon Brando) standing under the Pont de Bir-Hakeim in Paris, screaming out, “Fucking God!” His hair disheveled, he is wearing a long brown jacket and seems to be holding back tears. An adorable young woman (Maria Schneider) in a fashionable fluffy white coat and black hat with flowers passes by, stops and looks at him, then moves on. They meet again inside a large, sparsely furnished apartment at the end of Rue Jules Verne that they are each interested in renting. Both looking for something else in life, they quickly have sex and roll over on the floor, exhausted. For the next three days, they meet in the apartment for heated passion that the man, Paul, insists include nothing of the outside world — no references to names or places, no past, no present, no future; the young woman, Jeanne, agrees. Their sex goes from gentle and touching to brutal and animalistic; in fact, after one session, Bertolucci cuts to actual animals. The film is nothing if not subtle.

One of the most artistic films ever made about seduction, Bernardo Bertolucci’s controversial X-rated Last Tango in Paris is part of the Quad’s “Paris Stripped Bare” and “Pictures from the Revolution: Bertolucci’s Italian Period” series in addition to “Rated X.” Written by Bertolucci (The Conformist, The Spider’s Stratagem), who passed away in Rome in November at the age of seventy-seven, with regular collaborator and editor Franco Arcalli and with French dialogue by Agnès Varda (Le Bonheur, Vagabond), the film opens with credits featuring jazzy romantic music by Argentine saxophonist Gato Barbieri and two colorful and dramatic paintings by Francis Bacon, “Double Portrait of Lucian Freud and Frank Auerbach” and “Study for a Portrait,” that set the stage for what is to follow. (Bacon was a major influence on the look and feel of the film, photographed by Vittorio Storaro.) Bertolucci then cuts to a haggard man (Marlon Brando) standing under the Pont de Bir-Hakeim in Paris, screaming out, “Fucking God!” His hair disheveled, he is wearing a long brown jacket and seems to be holding back tears. An adorable young woman (Maria Schneider) in a fashionable fluffy white coat and black hat with flowers passes by, stops and looks at him, then moves on. They meet again inside a large, sparsely furnished apartment at the end of Rue Jules Verne that they are each interested in renting. Both looking for something else in life, they quickly have sex and roll over on the floor, exhausted. For the next three days, they meet in the apartment for heated passion that the man, Paul, insists include nothing of the outside world — no references to names or places, no past, no present, no future; the young woman, Jeanne, agrees. Their sex goes from gentle and touching to brutal and animalistic; in fact, after one session, Bertolucci cuts to actual animals. The film is nothing if not subtle.

A turning point in his career, John Waters’s Desperate Living is an off-the-charts bizarre, fetishistic fairy tale, the ultimate suburban nightmare. Mink Stole stars as Peggy Gravel, a wealthy housewife suffering yet another of her mental breakdowns. In the heat of the moment, she and the family maid, four-hundred-pound Grizelda Brown (Jean Hill), kill Peggy’s mild-mannered husband, Bosley (George Stover), and the two women end up finding refuge in one of the weirdest towns ever put on celluloid, Mortville, where MGM’s The Wizard of Oz and Babes in Toyland meet Russ Meyer’s Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill! (with some Kenneth Anger, Jack Smith, and Douglas Sirk thrown into the mix as well). “I ain’t your maid anymore, bitch! I’m your sister in crime!” Grizelda declares. Peggy and Grizelda move into the “guest house” of manly Mole McHenry (Susan Lowe) and her blonde bombshell lover, Muffy St. Jacques (Liz Renay). Mortville is run as a kind of fascist state by the cruel and unusual despot Queen Carlotta (Edith Massey), an evil shrew who enjoys being serviced by her men-in-leather attendants, issues psychotic proclamations, and is determined that her daughter, Princess Coo-Coo (Mary Vivian Pearce), stop dating her garbage-man boyfriend, Herbert (George Figgs). (Wait, Mortville has a sanitation department?) Camp and trash combine like nuclear fission as things get only crazier from there, devolving into gorgeous low-budget madness and completely over-the-top ridiculousness, a mélange of sex, violence, and impossible-to-describe lunacy that Waters himself claimed was a movie “for fucked-up children.”

A turning point in his career, John Waters’s Desperate Living is an off-the-charts bizarre, fetishistic fairy tale, the ultimate suburban nightmare. Mink Stole stars as Peggy Gravel, a wealthy housewife suffering yet another of her mental breakdowns. In the heat of the moment, she and the family maid, four-hundred-pound Grizelda Brown (Jean Hill), kill Peggy’s mild-mannered husband, Bosley (George Stover), and the two women end up finding refuge in one of the weirdest towns ever put on celluloid, Mortville, where MGM’s The Wizard of Oz and Babes in Toyland meet Russ Meyer’s Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill! (with some Kenneth Anger, Jack Smith, and Douglas Sirk thrown into the mix as well). “I ain’t your maid anymore, bitch! I’m your sister in crime!” Grizelda declares. Peggy and Grizelda move into the “guest house” of manly Mole McHenry (Susan Lowe) and her blonde bombshell lover, Muffy St. Jacques (Liz Renay). Mortville is run as a kind of fascist state by the cruel and unusual despot Queen Carlotta (Edith Massey), an evil shrew who enjoys being serviced by her men-in-leather attendants, issues psychotic proclamations, and is determined that her daughter, Princess Coo-Coo (Mary Vivian Pearce), stop dating her garbage-man boyfriend, Herbert (George Figgs). (Wait, Mortville has a sanitation department?) Camp and trash combine like nuclear fission as things get only crazier from there, devolving into gorgeous low-budget madness and completely over-the-top ridiculousness, a mélange of sex, violence, and impossible-to-describe lunacy that Waters himself claimed was a movie “for fucked-up children.”

Fed up with their lives, four old friends decide to literally eat themselves to death in one last grand blow-out. Cowritten and directed by Marco Ferreri (Chiedo asilo, La casa del sorriso), La Grande Bouffe features a cast that is an assured recipe for success, bringing together a quartet of legendary actors, all playing characters with their real first names: Marcello Mastroianni as sex-crazed airplane pilot Marcello, Philippe Noiret as mama’s boy and judge Philippe, Michel Piccoli as effete television host Michel, and Ugo Tognazzi as master gourmet chef Ugo. They move into Philippe’s hidden-away family villa, where they plan to eat and screw themselves to death, with the help of a group of prostitutes led by Andréa (Andréa Ferréol). Gluttons for punishment, the four men start out having a gas, but as the feeding frenzy continues, so does the flatulence level, and the men start dropping one by one. While the film, which won the FIPRESCI Prize at the 1973 Cannes Film Festival, might not be quite the grand feast it sets out to be, it still is one very tasty meal. Just be thankful that it’s not shown in Odoroma. Bon appetit!

Fed up with their lives, four old friends decide to literally eat themselves to death in one last grand blow-out. Cowritten and directed by Marco Ferreri (Chiedo asilo, La casa del sorriso), La Grande Bouffe features a cast that is an assured recipe for success, bringing together a quartet of legendary actors, all playing characters with their real first names: Marcello Mastroianni as sex-crazed airplane pilot Marcello, Philippe Noiret as mama’s boy and judge Philippe, Michel Piccoli as effete television host Michel, and Ugo Tognazzi as master gourmet chef Ugo. They move into Philippe’s hidden-away family villa, where they plan to eat and screw themselves to death, with the help of a group of prostitutes led by Andréa (Andréa Ferréol). Gluttons for punishment, the four men start out having a gas, but as the feeding frenzy continues, so does the flatulence level, and the men start dropping one by one. While the film, which won the FIPRESCI Prize at the 1973 Cannes Film Festival, might not be quite the grand feast it sets out to be, it still is one very tasty meal. Just be thankful that it’s not shown in Odoroma. Bon appetit!