Francis Jue and Daniel Dae Kim play father and son in Yellow Face (photo by Joan Marcus)

YELLOW FACE

Todd Haimes Theatre

227 West Forty-Second St. between Broadway & Eighth Ave.

Tuesday – Sunday through November 24, $70-$348

212-539-8500

www.roundabouttheatre.org

Three recently opened shows on Broadway feature television and movie stars either making their Great White Way debut or returning after a long absence, but, was we learn, success on the big and/or small screen does not always guarantee onstage triumph.

In an April 2021 interview in Vulture, actor and anti-Asian-hate activist Daniel Dae Kim said, “I take a great deal of pride in being Korean American. I know that not every representation is 100 percent something we can stand behind all the time, but I choose to look at things as whether they’re moving the needle of progress on a larger scale.” Talking about his and Grace Park’s departure from the successful Hawaii Five-O reboot in 2017 after the seventh season following a contract dispute — the two Asian Americans wanted equal pay with their Caucasian costars — Kim explained, “I had hopes that Hawaii Five-0 would be different because it was a show set in Hawaii, where the majority of people are not white. I thought it was going to be more of an ensemble show, and if you look at the early marketing and promotion for the show, where Grace Park and I were featured equally as prominently as anyone else, it led me to believe that it could be. I was proven to be wrong.”

In the article, he also discusses initially wanting to cast an Asian lead in the American version of the Korean television drama The Good Doctor, which his 3AD company produced, but eventually agreeing with showrunner David Shore and hiring white English actor Freddie Highmore.

Kim, who was born in South Korea, is now back on Broadway in the Great White Way debut of David Henry Hwang’s semiautobiographical 2007 Obie-winning Pulitzer finalist, Yellow Face, at the Todd Haimes Theatre through November 24. Kim plays a version of Hwang, known as DHH, a first-generation Chinese American playwright and activist who gets involved in a series of casting controversies. DHH makes a public stand against producer Cameron Mackintosh’s insistence on casting English actor Jonathan Pryce as a French-Vietnamese pimp known as the Engineer, altering his eyes and skin color to make him look more Asian; Pryce went on to win a Tony for his performance.

DHH, who won a Tony for his 1988 play, M. Butterfly, decides to write about “yellow face” in his next play, Face Value, choosing unknown actor Marcus G. Dahlman (Ryan Eggold) as the lead, believing he is at least part Asian. But when it turns out that the renamed Marcus Gee probably has no Asian blood in him at all, DHH convinces the actor that he must have had a Siberian Jewish ancestor, and things go haywire from there.

Yellow Face is told in flashback, with DHH often directly addressing the audience, guiding the tale while freely admitting the many mistakes he made. It starts with various public figures commenting on the Marcus Gee situation.

“Wow. That is one of the strangest stories I’ve ever heard,” Vice President Al Gore (Marinda Anderson) says.

“David Henry Hwang is a white racist asshole,” playwright Frank Chin (Kevin Del Aguila) declares.

“This is a tempest in an Oriental teapot,” Mackintosh (Shannon Tyo) insists.

DHH (Daniel Dae Kim) and Marcus Gee (Ryan Eggold) have different ideas of ethnic representation at Todd Haimes Theatre (photo by Joan Marcus)

Among the other real-life famous and not-so-famous people chiming in at one point or another are casting director Vinnie Liff, author Gish Jen, theater critics Frank Rich and Michael Riedel, New York City mayor Ed Koch, columnist George F. Will, talk show host Dick Cavett, Taiwanese American computer scientist Wen Ho Lee, actors B. D. Wong, Mark Linn-Baker, Lily Tomlin, Gina Torres, Jane Krakowski, and Margaret Cho, politicians Fred Thompson, Sam Brownback, Tom Delay, and Richard Shelby, and theater luminaries Bernard Jacobs, Joe Papp, and Jerry Zaks, all played by Anderson, Del Aguila, Tyo, and Francis Jue; Jue also portrays DHH’s father, HYH, an immigrant immensely proud of his success in the financial sector but whose bank finds itself in a bit of hot water with a congressional committee as the opening of Face Value approaches.

Kim is most well known for playing Jin-Soo Kwon on the seven seasons of Lost and Chin Ho Kelly for seven years on the Hawaii Five-O reboot; he has also appeared onstage in New York City, Los Angeles, and London since 1991, including Romeo and Juliet, A Doll’s House, The Tempest, The King and I, and Hwang’s Golden Child. He is amiable and confident as DHH, instantly gaining the audience’s faith as he balances the sublime and the ridiculous with acute self-awareness and self-deprecation; he’s particularly strong as DHH digs himself into a deeper and deeper hole. His casting in and of itself is fascinating; there’s been a recent movement for people of Asian descent not to be called “Asian” but to be identified by the specific country they or their ancestors come from; in this case, the South Korean Kim is playing the Chinese American Hwang.

Eggold (Dead End, All My Sons) is hilarious as Marcus, a regional actor who can’t believe how his stature has changed once he agreed to pretend to be Asian, getting hooked on the hoopla. Keller (Dig, Shhhh) excels as the announcer and a reporter identified as “Name withheld on advice of counsel,” Jue, who originated the role of HYH at the Public and played an alternate version of DHH in Hwang’s autobiographical soft power, is gleeful as the father, and Tyo (The Comeuppance, The Chinese Lady), del Aguila (Some Like It Hot, Frozen), and Anderson (Merry Me, Sandblasted) shift seamlessly from role to role.

Arnulfo Maldonado’s changing sets and Yee Eun Nam’s projections keep the audience fully engaged under the smooth-flowing direction of Leigh Silverman, who helmed the original production of Yellow Face as well as Hwang’s Chinglish, Kung Fu, and Golden Child, her familiarity with the material delivering a fun experience while making its important points.

Mia Farrow and Patti LuPone return to Broadway in Jen Silverman’s The Roommate (photo by Matthew Murphy)

THE ROOMMATE

Booth Theatre

222 West 45th St. between Broadway & Eighth Ave.

Tuesday – Sunday through December 15, $48 – $321

theroommatebway.com

The Broadway premiere of Jen Silverman’s 2015 play, The Roommate, dooms itself from the very start. Longtime friends Mia Farrow and Patti LuPone take the stage together, their names projected across the top of the set, and they bask in the uproarious applause of the audience. They exit, then return seconds later in character. While the laudatory moment removes the need for applause at the beginning of the actual narrative, it also makes sure we never forget we are watching a pair of superstar performers, even though the success of the play — any play — depends on our believing in the fiction that is about to unfold before us.

Two years ago, LuPone, who has won two Grammys and three Tonys, announced she was retiring from the Great White Way because of Actors’ Equity’s lack of support of its union members, writing on Twitter, “Quite a week on Broadway, seeing my name being bandied about. Gave up my Equity card; no longer part of that circus. Figure it out.” She later told People magazine, “I just didn’t want to give them any more money. . . . And I don’t know when I’m going to be back on stage.”

Meanwhile, Farrow, who has never been nominated for an Oscar or Tony, last appeared on Broadway in 2014 in Love Letters, sitting at a table with Brian Dennehy and reading A. R. Gurney’s epistolary play. Here only other Broadway appearance was costarring with Anthony Perkins in Bernard Slade’s 1980 Romantic Comedy. (She made her off-Broadway debut as Cecily Cardew in The Importance of Being Earnest in 1963.)

So there was a lot of buzz surrounding LuPone and Farrow teaming up at the Booth Theatre for a play about an odd couple living together in rural Iowa. Unfortunately, they lack any kind of chemistry, and three-time Tony-winning director Jack O’Brien (Shucked, The Invention of Love) can’t get around Jen Silverman’s inconsequential, clichéd script.

Farrow is Sharon, a divorced mother from Illinois who has made a peaceful life for herself in a large home in Iowa City. She likes things as they are, simple, without complications, but she seeks out a roommate, both for financial reasons and, perhaps, friendship.

LuPone is Robyn, a divorced mother from the Bronx who is ready for a major change. She is not exactly what Sharon expected: a tough-talking vegan lesbian whose black leather provides a sharp contrast to Sharon’s loose-fitting sun dresses. (The costumes are by Bob Crowley, who also designed the set, a skeletal house with a kitchen and a small staircase leading up.)

After learning these facts about Robyn, Sharon declares, “I mean. A roommate! I’ve never had a roommate. I’m sixty-five years old. A roommate!”

While there is no reason an actor can’t play well above or below their age, the line gets a curious stare from the audience, who know Farrow cannot be sixty-five. (In actuality, Farrow is seventy-nine and LuPone is seventy-five). In a script note, Silverman suggests, “In terms of age, you should feel free to adjust the character’s age to fit the actor.” Because the production made such a big deal of Farrow and LuPone’s star power when they first took the stage, the number sticks out as false.

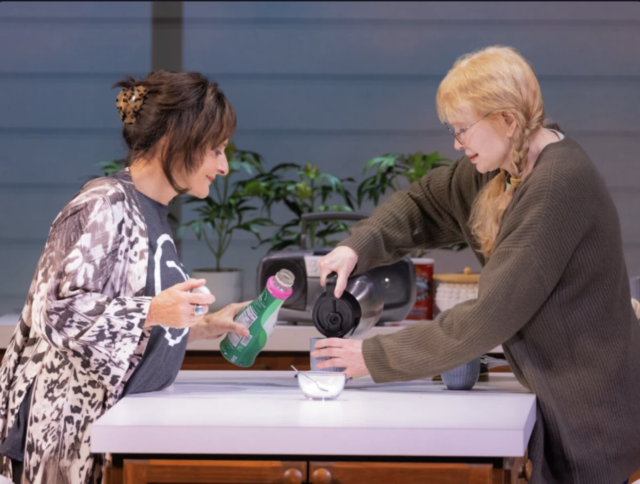

Robyn (Patti LuPone) and Sharon (Mia Farrow) form an odd couple in The Roommate (photo by Matthew Murphy)

As the play continues, we learn more about both women, their prejudices, their pasts, and their futures. Each is dealing with not being on the closest of terms with their children. While Robyn knows about what’s going on around the world, Sharon seems to be happily stuck in an old-fashioned bubble straight out of a Norman Rockwell painting, oblivious to what is happening right outside her door, although that changes as she grows more and more intrigued with what she at least initially considers Robyn’s vices.

The Roommate is in part a riff on The Odd Couple, with Sharon a fuddy-duddy like Felix Ungar, Robyn a more coarse figure like Oscar Madison. (At the 2017 Williamstown Theater Festival, S. Epatha Merkerson was Sharon, and Jane Kaczmarek was Robyn.)

But the effects they have on each other are difficult to believe, not fully formed. Silverman (Collective Rage: A Play in 5 Betties, Spain) might have a lot to say about human vulnerability and morality and female friendship, but she goes too far off the rails in the play’s slow-moving ninety minutes.

Farrow is lovely as Sharon, every line delivered with a touch of wonder, going especially high and squeaky when something Robyn reveals surprises her. She handles Sharon’s absurd shifts in right and wrong with aplomb, just going with the flow, but LuPone (Company, Shows for Days) looks like she’d rather be just about anywhere else, as if she knows she made a mistake choosing this play as her return to the stage. Hopefully Farrow and LuPone will join forces again, only next time in a better piece of theater.

“There’s a great liberty in being bad,” Robyn tells Sharon, who repeats the line later on.

It’s a catchy phrase that never comes to fruition in The Roommate.

Jacob McNeal (Robert Downey Jr.) gets good and bad news from his doctor (Ruthie Ann Miles) in McNeal (photo by Matthew Murphy and Evan Zimmerman)

McNEAL

Vivian Beaumont Theater at Lincoln Center Theater

150 West 65th St. between Broadway & Amsterdam Ave.

Tuesday – Saturday through November 24, $195.50-$371

212-362-7600

www.lct.org

The night before I saw Ayad Akhtar’s McNeal at the Vivian Beaumont Theater at Lincoln Center, I watched Dario Argento’s 1982 giallo cult classic, Tenebrae, starring Tony and Oscar nominee and New York City native Anthony Franciosa as Peter Neal, a popular American novelist on a book tour in Italy, accompanied by his agent, Bullmer (John Saxon), and his assistant, Anne (Daria Nicolodi). One critical scene involves Neal sitting down for a television interview with superfan Christiano Berti (John Steiner). Fact and fiction start weaving in and out of the plot as violent scenes from his books come to life in a series of murders.

In McNeal, Tony and Emmy winner and New York City native Robert Downey Jr. is the title character, Jacob McNeal, a popular American novelist who, while being examined by his doctor, Sahra Grewal (Ruthie Ann Miles), gets notified that he has won the Nobel Prize in Literature, an award he feels he deserved many years ago. His agent, Stephie Banic (Andrea Martin), immediately contacts his publisher to negotiate a new contract, and the Times finally agrees to do a front-page magazine profile of him, sending over New York Times journalist Natasha Brathwaite (Brittany Bellizeare), who is not planning on doing a puff piece. “Were you a diversity hire?” he asks her, kicking off an awkward interview. McNeal flirts with using AI for his Nobel acceptance speech, but soon he is counting on AI for much more as fact and fiction intermingle.

I prefer Tenebrae.

Jacob McNeal (Robert Downey Jr.) says way too much in interview with journalist Natasha Brathwaite (Brittany Bellizeare) (photo by Matthew Murphy and Evan Zimmerman)

In his Broadway debut, Downey, who first acted on the stage in Alms for the Middle Class in Rochester in 1983, delivers a solid performance as the self-destructive McNeal, who has a serious kidney issue but can’t stop going back to the bottle. (Downey himself has had problems with drugs and alcohol and has been drug-free for more than twenty years.) He looks completely comfortable in McNeal’s skin, playing a character who is adorable and unlikable at the same time, as it’s difficult to dismiss his misogyny as just exemplary of the way things used to be. The sets by Michael Yeargan and Jake Barton rise and lower from above and below as Barton’s projections beam out visual stimuli, from texts and close-ups to the spewing of words and letters.

In such previous works as Junk, The Invisible Hand, Corruption, and the Pulitzer Prize–winning Disgraced, Akhtar has proved to be a master of complex plots, tackling such issues as politics, race, religion, the financial industry, capitalism, and personal ambition. In McNeal, however, he takes on too much, straying from the central focus on the future of AI and its impact on literature and humanity itself to include scenes that feel like they’re from another play; even director Bartlett Sher (The King and I, Oslo), who has been nominated for eight Tonys and won one, is unable to weave together subplots involving McNeal’s son, Harlan (Rafi Gavron), with its bizarre revelation; McNeal’s flirtations with Banic’s assistant, Dipti (Saisha Talwar), and fondness for Harvey Weinstein, as his agent’s actions confound believability; his liberal use of the lives of his friends and relatives in his plots; and his relationship with journalist Francine Blake (Melora Hardin).

The 105-minute show does have a magical finale, but it’s not enough to save it. Near the end, a typing prompt acknowledges that the audience is “confused by what is real and what isn’t.”

There was no such problem in Tenebrae.

[Mark Rifkin is a Brooklyn-born, Manhattan-based writer and editor; you can follow him on Substack here.]