Theodore “Hickey” Hickman (Nathan Lane) dispenses a whole lot more than just free drinks in THE ICEMAN COMETH (photo by Richard Termine)

Brooklyn Academy of Music

BAM Harvey Theater

651 Fulton St. between Ashland & Rockwell Pl.

Through March 15, $35-$180

BAM Talk with Brian Denney and Nathan Lane, moderated by Linda Winer, $25, 7:30

718-636-4100

www.bam.org

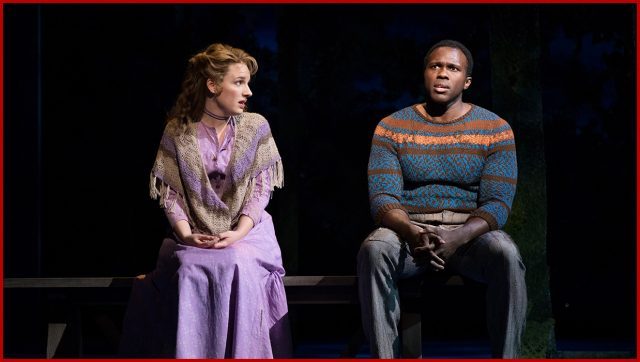

You’d be hard-pressed to find a sorrier collection of forgotten men, real or fictitious, than the group of pathetic drunks populating Eugene O’Neill’s great American tragedy, The Iceman Cometh, now enjoying a stirring four-hour, forty-five-minute revival at BAM (if the word “enjoy” can be used in describing this staggering work in any way). Written in 1939 but not produced until after WWII, in 1946, the play opens with most of a ragtag bunch of bums asleep on tables in Harry Hope’s (Stephen Ouimette) Last Chance Saloon and rooming house on the Bowery, awaiting the annual arrival of Theodore “Hickey” Hickman (Nathan Lane), a traveling salesman who comes to the bar once a year to celebrate Harry’s birthday by buying drinks for everyone. While the other poor souls are passed out, former anarchist Larry Slade (Brian Dennehy), pouring himself another shot of whiskey, tells bartender Rocky Pioggi (Salvatore Inzerillo), “I’ll be glad to pay up — tomorrow. And I know my fellow inmates will promise the same. They’ve all a touching credulity concerning tomorrows. It’ll be a great day for them, tomorrow — the Feast of All Fools, with brass bands playing! Their ships will come in, loaded to the gunwales with cancelled regrets and promises fulfilled and clean slates and new leases!” A moment later, Rocky, who speaks in a tough dem and doze New Yorkese, says to Larry, “De old Foolosopher, like Hickey calls yuh, ain’t yuh? I s’pose you don’t fall for no pipe dream?” To which Larry explains, “I don’t, no. Mine are all dead and buried behind me. What’s before me is the comforting fact that death is a fine long sleep, and I’m damned tired, and it can’t come too soon for me.”

That mood of hopelessness sets the tone of the play, with Larry the leading “Foolosopher” of men whose pipe dreams have long since turned into nightmares, with nothing to look forward to except the next, preferably free, drink. Slowly but surely, the others awake, wondering where Hickey is. “I was dreamin’ Hickey come in de door, crackin’ one of dem drummer’s jokes, wavin’ a big bankroll and we was all goin’ be drunk for two weeks. Wake up and no luck,” gambler Joe Mott (John Douglas Thompson) opines. Also arising are Hope, circus man Ed Mosher (Larry Neumann Jr.), Harvard Law alum Willie Oban (John Hoogenakker), former Boer Commando General Piet Wetjoen (John Judd), former British Infantry Captain Cecil Lewis (John Reeger), former anarchist editor Hugo Kalmar (Lee Wilkof), young former anarchist Don Parritt (Patrick Andrews), and former war correspondent James Cameron, better known as “Jimmy Tomorrow” (James Harms). But these men — along with day bartender Chuck Morello (Marc Grapey), his prostitute girlfriend, Cora (Kate Arrington), and two streetwalkers who work for Chuck, Margie (Lee Stark) and Pearl (Tara Sissom) — have long ago run out of tomorrows. So they spend their days and nights slowly drinking themselves to death, some hanging on to those pipe dreams, waiting for Hickey like Vladimir and Estragon will do a few years later in Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, except in this case, Godot/Hickey shows up, waving a wad of bills and waking everyone up — but it turns out to be not nearly as satisfying as they were anticipating.

Harry Hope (Stephen Ouimette) and Ed Mosher (Larry Neumann Jr.) try to hold on to their pipe dreams in a downtrodden Bowery bar (photo by Richard Termine)

Dressed in a sharp suit and wearing an even more impressive smile, Hickey bursts in at the end of act one, but he is not quite the good-time guy they have all come to know. Instead, Hickey is no longer drinking, and he has arrived with a message for each and every one of his minions, determined to tell them the truth about their sad lives. He is like a boisterous Bill W., the traveling stock speculator who founded Alcoholics Anonymous. He’s going to buy them all drinks but make them pay in other ways, forcing them to look at what they’ve become. “If anyone wants to get drunk, if that’s the only way they can be happy, and feel at peace with themselves, why the hell shouldn’t they? They have my full and entire sympathy,” Hickey tells Harry. “I know all about that game from soup to nuts. I’m the guy that wrote the book. The only reason I’ve quit is — well, I finally had the guts to face myself and throw overboard the damned lying pipe dream that’d been making me miserable, and do what I had to do for the happiness of all concerned — and then all at once I found I was at peace with myself and I didn’t need booze any more. That’s all there was to it.” Of course, that’s not all there is to it, as is revealed during the next three acts.

Larry Slade (Brian Dennehy) is determined to drink himself to death in Eugene O’Neill’s classic American tragedy (photo by Richard Termine)

In 1990, Chicago’s Goodman Theatre staged a revival of The Iceman Cometh, directed by Robert Falls and starring Dennehy as Hickey. More than twenty years later, Dennehy told longtime collaborator Falls that he wanted to play Larry in a new production. Upon hearing that, Lane contacted Falls, explaining that he had always dreamed of playing Hickey. The show was a huge success in Chicago in 2012, and it is now a huge success at BAM, where it fits in wonderfully with the Harvey’s artfully distressed shabby chic interior. The Harvey doesn’t usually use a curtain, but it does so for The Iceman Cometh, revealing a different set for each act, designed by Kevin Depinet (inspired by John Conklin); there is actually an audible gasp when the third act begins in the main bar area, shown in an unusual narrow perspective leading to a doorway that offers a kind of freedom — and real life — that no one in the play seems to want. Natasha Katz’s lighting design often keeps things in the dark, echoing the lost dreams of these miserable characters. This nearly five-hour production, with three full intermissions, might be epic in scope, but it is beautifully paced by Falls, never dragging, instead moving with a sometimes exhilarating gait.

Dennehy (Love Letters, Death of a Salesman) fully captures the heartbreaking duality that exists inside Larry, a clearly intelligent man who has given up his reason for being, someone who could make a difference in the life of all those around him — especially Don, who is seeking him out as a father figure — but he has instead buried himself in the bottle. Lane (It’s Only a Play, The Nance) shines as Hickey, bringing an exuberance to the role that occasionally goes over the top, particularly in the final monologue, not quite hitting its darker quality, but he and Dennehy have a beguiling camaraderie together in these iconic roles. (The play premiered on Broadway in 1946 and has been revived on the Great White Way in 1973, 1985, and 1999; over the years, Hickey has been portrayed by James Barton, James Earl Jones, Dennehy, Lee Marvin, Kevin Spacey, and, most famously, Jason Robards onstage and on film, while Slade has been played by Robert Ryan, James Cromwell, Conrad Bain, Tim Pigott-Smith, and Patrick Stewart.) The Iceman Cometh has never been an easy show to put on or to sit through; don’t be surprised when you see a handful of people exiting the theater and hailing cabs at each intermission. But it’s their loss, as this is a staggering production that looks deeply into the heart of America with a raw honesty that compels audiences to look deep into their own hearts as well.