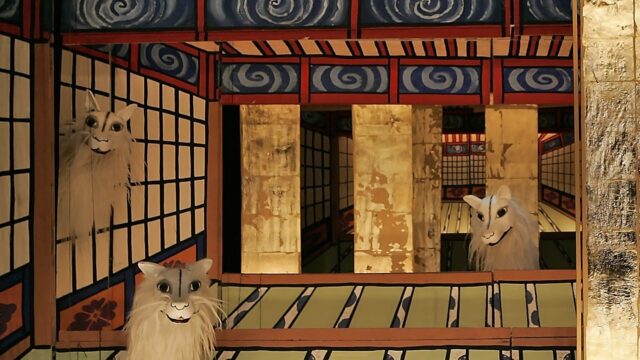

Sujin Kim reimagines Shūji Terayama’s Duke Bluebeard’s Castle as macabre Harajuku burlesque at Japan Society (photo © Ayumi Sakamoto)

DUKE BLUEBEARD’S CASTLE

Japan Society

333 East 47th St. at First Ave.

January 15-18, $36-$48

www.japansociety.org

utrfest.org

Korean-Japanese director Sujin Kim’s macabre Harajuku burlesque adaptation of Shūji Terayama’s Duke Bluebeard’s Castle is an exhilarating two hours of nonstop fun, a wildly imaginative celebration of all that angura, or Japanese underground, unconventional theater, has to offer. For the show, which runs January 15–18 at Japan Society as part of the Under the Radar festival, Kim has brought together an inspiring multidisciplinary cast of more than thirty, including the tantalizing cabaret duo Kokusyoku Sumire, consisting of soprano vocalist and accordionist Yuka and violinist Sachi, who wear adorable outfits with light-up rabbit ears; magician Syun Shibuya, who, in a sharp-fitting tux, does card tricks, pulls doves out of a hat, and dazzles with mind-boggling costume changes; the delightful aerialist Miho Wakabayashi, who has been detailing her New York City trip here; and the experimental Japanese company Project Nyx, which was founded in 2006 by Kim’s wife, Kanna Mizushima, and specializes in “entertainment Bijo-geki, all-female cross-dressing theater.”

We get a taste of what’s to come when, early on, the stage manager (Misa Homma) tells Judith (Rei Fujita), who is portraying Bluebeard’s prospective seventh wife and closely checking the script, “You know what? — Things don’t always follow the script, y’know? Let’s see your improv muscles!”

The narrative regularly pops in and out of the Bluebeard fairy tale, which was written in 1697 by French author Charles Perrault; the self-referential story of the staging of the show; and the acknowledgment that it is being held at Japan Society, maintaining an improvisatory feel throughout.

“Wait, you’re saying the stage manager is doubling as the costume designer’s assistant in this production?” Bluebeard’s first wife (Miki Yamazaki) says to the stage manager while Carrot the Prompter (Ran Moroji) rubs her feet. Carrot had just amateurishly spoken a stage direction out loud: “Whistles dramatically and pretends to be a bird flying away.”

The play unfolds at a furious pace, so fast that it’s sometimes difficult to read the English surtitles, which are projected on small, raised monitors at the left and right sides; it can get a little frustrating, as you don’t want to miss a second of what’s happening onstage.

Asuka Sasaki’s kawai costumes and the far-out, colorful wigs are spectacular, like the best cosplay comic-con contest ever, with circuslike lighting by Tsuguo Izumi + RISE and enveloping sound by Takashi Onuki. Choreographer Taeko Okawa takes advantage of every piece of Satoshi Otsuka’s set, highlighted by seven white doors that flip to seven mirrors held by the seven wives in slinky black. As they dance with the mirrors, reflections shimmer throughout the space.

Kokusyoku Sumire’s songs are charming and engaging, including “[Doppelgänger],” in which they explain, “Even if I hide perfectly / There are times when misfortune finds me. / If I were to suppress this tormenting pain, / Would I be allowed to wish for your happiness?,” and poetic, as when they sing, “Walking in shadows, careful not to stumble, counting to nine, who are you? / The moonlight is full, playing the song of joy. If I close my eyes, I should be able to see everything.”

Dance with seven door-mirrors is a highight of Duke Bluebeard’s Castle (photo © Ayumi Sakamoto)

The scene titles in the script are not projected on the monitors but give a good idea of what audiences are in store for, including “The Bride in the Bathtub,” “A Goblin Peeks from Behind the Curtain,” “Don’t ruin my script with your life,” and “The Maestro of the Puppet Killers.” In “A Pig and a Rose,” which features some of the most hilarious dialogue in the play, Copula the Attendant (Chisato Someya) complains to the second wife (Yoshika Kotani) that the seventh wife has been miscast: “Her expressions are our hand-me-down, her heart is like a plastic trash can, and oh, her face — is the stuff that splashes out from an overflowing pit latrine. . . . She is Madam’s used tampon! Madam’s vomit — her face is fit for a manhole cover in a sewer!” The second wife is overjoyed, proclaiming, “So thrilling!!! Insults are divine, don’t you agree, Judith?”

Fujita and Homma stand out in the fantastic cast, which also features Ruri Nanzoin as Coppélius the puppeteer, You Yamagami as the costume designer, Haruka Yoshida as the debt collector, Nozomi Yamada as the actor, Yume Tsukioka as Aris, Hinako Tezuka as Teles, Kaho Asai as the magician’s assistant, Wakabayashi as the fourth wife, Mizushima as the fifth wife, Sayaka Ito as the third wife, and Mayu Kasai as wife number six. Don’t worry if you can’t keep it all straight; just let the extravaganza dazzle you time and time again.

Kim has a dream of presenting Terayama’s work in a tent along the New York City waterfront. Here’s hoping that’s next for this immensely talented creator.

[There will be a preshow lecture on Terayama by UCLA professor emerita Carol Fisher Sorgenfrei at 6:30 on January 17. Ticket holders on January 17 and 18 are invited to see the current exhibit, “Bunraku Backstage,” in the Japan Society Gallery; there is also a display of rare Terayama artifacts on view, including scripts, letters, photos, and more from the La MaMa Archive.]

[Mark Rifkin is a Brooklyn-born, Manhattan-based writer and editor; you can follow him on Substack here.]