Kirsten (Kelli O’Hara) and Joe (Brian d’Arcy James) hold on for dear life in Days of Wine and Roses (photo by Ahron R. Foster)

DAYS OF WINE AND ROSES

Atlantic Theater Company

Linda Gross Theater

336 West 20th St. between Eighth & Ninth Aves.

Tuesday – Sunday through July 16, $112-$252

atlantictheater.org

There’s no sign of Johnny Mercer and Henry Mancini’s lush, overdramatic Oscar- and Grammy-winning title song from Blake Edwards’s 1962 film, Days of Wine and Roses, in the world premiere musical adaptation that opened tonight at the Atlantic. While its inclusion might not have helped, it certainly couldn’t have hurt.

Written by JP Miller, Days of Wine and Roses was initially performed live on Playhouse 90 in 1958, directed by John Frankenheimer and starring Cliff Robertson as Joe Clay and Piper Laurie as Kirsten Arnesen, eager young corporate colleagues whose burgeoning love is fueled by the bottle. Miller adapted the play for the screen, with Jack Lemmon as Joe and Lee Remick as Kirsten.

Composer and lyricist Adam Guettel and book writer Craig Lucas, who previously collaborated on the smash hit The Light in the Piazza, which won six Tonys, have now turned Days of Wine and Roses into an all-wet, thorny musical, supremely disappointing especially given its star power, with Brian d’Arcy James as Joe and Kelli O’Hara as Kirsten. It starts off promising, on board a yacht where Joe, a fast-talking New York City PR man, is entertaining male clients by hustling them into a back room and plying them with booze and babes. He assumes that Kirsten is one of his procured good-time girls, but she’s actually the secretary to his boss. A narrow pool of water at the front of the stage casts shimmering reflections across the characters, and a series of movable doors change colors like a mood ring (the set is by Lizzie Clachan, with lighting by Ben Stanton), but a life preserver ring in the corner is a harbinger of their fate.

Despite recognizing him as a player, Kristen agrees to have dinner with him, where he talks her into having her first alcoholic drink ever, a Brandy Alexander. That single indulgence leads them down a dark path of lies and deception as they get married, have a daughter, Lila (Ella Dane Morgan), and struggle personally and professionally because of their alcoholism. While Joe attempts sobriety through Alcoholics Anonymous with his sponsor, Jim Hungerford (David Jennings), Kirsten seeks refuge with her strict Norwegian father (Byron Jennings), who never liked Joe. The set opens up to reveal a seemingly impossible greenhouse, where Mr. Arnesen grows plants for sale, but it only spells more trouble for Joe and Kirsten, whose own growth is stunted by the bottle.

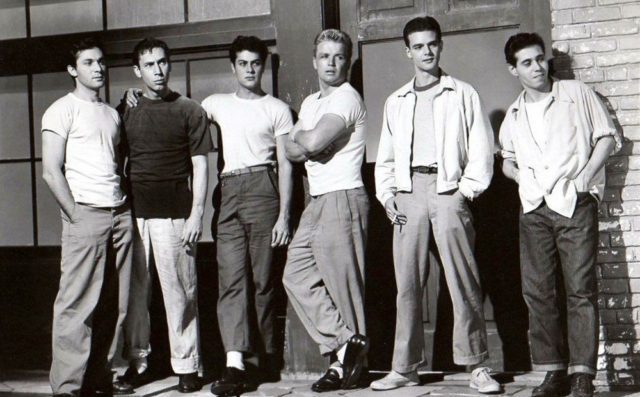

Days of Wine and Roses explores love and alcoholism at the Atlantic (photo by Ahron R. Foster)

In the show’s first song, “Magic Time,” Joe charmingly sings his dialogue to various people on the boat, including his assistant, Rad (Ted Koch), a client, Delaney (Byron Jennings), and Kirsten. “I’m not here for the fun,” she tells Joe, who replies in song, “Might be why you aren’t having any.” She answers, “Or . . . it might be you.” Their repartee is fast and witty, with sweet music by Guettel, but it quickly devolves after that as the score becomes laborious and the lyrics mundane. “Now I have / all I need / now that I’m your mama,” Kirsten sings to Lila. “There is a man who loves you / as the water loves the stone / and the stone adores the hillside / where the wind has always blown,” Joe sings to Kirsten. “Look, Daddy / Do you see the sun / the circle getting smaller / going to bed now / tucked in safe for the night,” Lila sings to Joe.

Tony nominee d’Arcy James (Into the Woods, Something Rotten!) is excellent channeling Lemmon as the outgoing Joe, but the small theater can’t contain O’Hara’s powerful, operatic voice. Tony nominee Lucas (Amélie, An American in Paris) stuffs too much plot into ninety minutes; the story jumps around, not allowing relationships to be properly nurtured. Tony-nominated director Michael Greif (The Low Road, Dear Evan Hansen) is unable to find enough balance in the characters or the bumpy narrative, which feels like a series of barely related vignettes and repetitive scenes. In addition, the only ones who sing are Joe, Kirsten, and Lila, adding to the arbitrariness.

Miller named the play after a line in the 1896 poem “Vitae Summa Brevis Spem Nos Vetat Incohare Longam,“ in which Ernest Dowson writes, “They are not long, the weeping and the laughter, / Love and desire and hate; / I think they have no portion in us after / We pass the gate. / They are not long, the days of wine and roses: / Out of a misty dream / Our path emerges for a while, then closes / Within a dream.” The title of the poem comes from an ode by Horace: “The brief sum of life denies us the hope of enduring long.” Guettel and Lucas’s adaptation lacks the poetry of its inspirations. In order for the story to work, you have to believe in the love between Joe and Kirsten, beyond their dependence on drink, but in this case it’s hard to make that connection.

Kirsten (Kelli O’Hara) and Joe (Brian d’Arcy James) get lost in the darkness of alcoholism in Days of Wine and Roses (photo by Ahron R. Foster)

In the show, Kirsten is reading Draper’s Self Culture, a 1907 educational series that her father started her off on when she was a child. She’s up to the fourth volume, Exploration, Travel, and Invention; in the introduction, Tufts president Frederick William Hamilton writes, “Exploration, Travel, and Invention are three phases of man’s unceasing search for the unknown. One of the most remarkable of human instincts, one of those also which most sharply differentiate man from other animals, is this constant desire to penetrate the unknown, to solve the mysteries which lie all about us. Humanity has never learned to be quiescent in the face of mystery.”

Theater is all about exploration, travel, and invention, taking audiences on journeys of the heart, mind, body, and soul, penetrating the unknown and confronting life’s endless mysteries. Unfortunately, Days of Wine and Roses turns out to be a haphazard trip, with the main mystery being why it needs to be a musical at all.