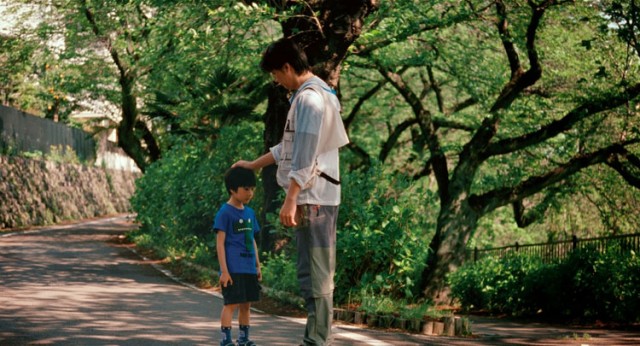

Kōji Yakusho goes face-to-face with Masaharu Fukuyama in Hirokazu Kore-eda’s The Third Murder

THE THIRD MURDER (三度目の殺人) (SANDOME NO SATSUJIN) (Hirokazu Kore-eda, 2017)

Quad Cinema

34 West 13th St. between Fifth & Sixth Aves.

July 20-26

212-255-2243

www.wildbunch.biz

quadcinema.com

Japanese auteur Hirokazu Kore-eda, the master of the intimate, intricate family drama, changes gears in the gripping legal thriller The Third Murder. Kore-eda, whose Shoplifters won the Palme d’Or at Cannes this year, started his career making documentaries; since he turned to fiction, often inspired by actual events (including in his own life), his films — Still Walking, After the Storm, Our Little Sister, Like Father, Like Son — have been infused with an organic feeling of realism. That sensibility also shines through in The Third Murder, which is essentially a search for the truth in its many forms and disguises. Masaharu Fukuyama stars as Tomoaki Shigemori, a defense attorney who takes on the case of Misumi (Kōji Yakusho), a factory worker who is facing the death penalty for killing his boss, a crime he has confessed to.

Japanese auteur Hirokazu Kore-eda, the master of the intimate, intricate family drama, changes gears in the gripping legal thriller The Third Murder. Kore-eda, whose Shoplifters won the Palme d’Or at Cannes this year, started his career making documentaries; since he turned to fiction, often inspired by actual events (including in his own life), his films — Still Walking, After the Storm, Our Little Sister, Like Father, Like Son — have been infused with an organic feeling of realism. That sensibility also shines through in The Third Murder, which is essentially a search for the truth in its many forms and disguises. Masaharu Fukuyama stars as Tomoaki Shigemori, a defense attorney who takes on the case of Misumi (Kōji Yakusho), a factory worker who is facing the death penalty for killing his boss, a crime he has confessed to.

Previously convicted killer Misumi (Kōji Yakusho) keeps changing his story even after confessing in gripping legal procedural

But every time Shigemori meets with Misumi — separated by glass in small rooms in a prison that makes each of them look trapped, as well as equating them as if the glass were a mirror — Misumi, who has previously served thirty years for double murder, slightly alters his story or adds new details that force Shigemori and his legal team to reevaluate their defense strategy and question not only why Misumi did it but whether he is even the guilty party despite his confession. But Shigemori is not necessarily interested in the facts, only information that can help him prevent Misumi’s execution, whether true or not. While Shigemori’s father, Daisuke Settsu (Kōtarō Yoshida), thinks his son is way off base, Akira Kawashima (Shinnosuke Mitsushima) keeps investigating further. As the mystery widens, the victim’s wife (Yuki Saito) and daughter, Sakie Yamanaka (Suzu Hirose), get involved and Misumi’s daughter tries to stay out of it as Shigemori also has to deal with his own daughter (Aju Makita), who has a knack for getting into trouble and lying to her parents.

Mother (Yuki Saito) and daughter (Suzu Hirose) deal with a brutal killing in The Third Murder

The moral dilemma at the heart of The Third Murder is a fascinating one, since Kore-eda opens the film, which he wrote, directed, and edited, with a brutal scene in which Misumi murders his boss and burns the body in a field by a river. There is no doubt that it’s Misumi; a close-up shows the look in his eyes and the bloodstains on his face as he watches the flames. But as Shigemori’s doubts grow, so do the viewer’s, as if Kore-eda is reminding us to question everything we see, even when caught on camera. He was inspired to make the film after having a discussion with a lawyer friend who said that uncovering the truth is not necessarily the goal of courts or lawyers, so Kore-eda decided to make a film about a lawyer who becomes obsessed with the truth, even if it has no bearing on the guilt or innocence of his client. He did extensive research, holding mock trials and interview sessions and having cinematographer Mikiya Takimoto watch Michael Curtiz’s Mildred Pierce — Kore-eda also has cited David Fincher’s Seven and Akira Kurosawa’s High and Low as influences — before using CinemaScope for the first time in order to give the film more breadth. No mere genre exercise, The Third Murder is a deep, multilayered, first-rate crime drama by one of the world’s best directors, searching for truth in character, narrative, and film itself.

In such films as

In such films as

Taiwanese auteur Hou Hsiao-hsien pays tribute to master filmmaker Yasujirō Ozu’s centenary with Café Lumiere, a beautifully lyrical yet elegantly simple drama about a young woman making her way through life. Pop star Yo Hitoto stars as Yoko, a woman who spends much of her time riding trains and trolleys to visit bookstore owner Hajime (the always excellent Tadanobu Asano) and to find out more about Chinese composer Jiang Wenye. She also returns home to her stepmother (Kimiko Yo) and father (Nenji Kobayashi); the latter doesn’t react when he finds out that Yoko is pregnant and does not intend to marry her boyfriend. In fact, there are barely any emotional reactions at all, although there are plenty of trains taking the characters where they seemingly want to be. Cinematographer Lee Pingping shot Café Lumiere on location with natural sound and lighting; his camera often lingers statically on a scene as the characters walk in and out of the carefully composed frame and are heard off-screen, in long takes, furthering the illusion of reality — mimicking the truth Ozu strove for in his work. In essence, the film has no beginning, no middle, and no end; it is 104 dazzling minutes in the life of a fascinating woman and her friends and relatives. Café Lumiere is screening December 4 at 4:30 and December 6 at 7:30 as part of the Film Society of Lincoln Center festival “Ozu and His Afterlives,” which honors the 110th anniversary of the master filmmaker’s birth and the 50th anniversary of his death; he died on his birthday at the age of sixty in 1963. The series features Ozu’s An Autumn Afternoon and Equinox Flower in addition to seven works that were either directly or indirectly inspired by Ozu and his unique style, including Hirokazu Kore-eda’s Still Walking, Jim Jarmusch’s Stranger Than Paradise, Aki Kaurismäki’s The Match Factory Girl, Claire Denis’s 35 Shots of Rum, Pedro Costa’s In Vanda’s Room, and Wim Wenders’s Tokyo-Ga.

Taiwanese auteur Hou Hsiao-hsien pays tribute to master filmmaker Yasujirō Ozu’s centenary with Café Lumiere, a beautifully lyrical yet elegantly simple drama about a young woman making her way through life. Pop star Yo Hitoto stars as Yoko, a woman who spends much of her time riding trains and trolleys to visit bookstore owner Hajime (the always excellent Tadanobu Asano) and to find out more about Chinese composer Jiang Wenye. She also returns home to her stepmother (Kimiko Yo) and father (Nenji Kobayashi); the latter doesn’t react when he finds out that Yoko is pregnant and does not intend to marry her boyfriend. In fact, there are barely any emotional reactions at all, although there are plenty of trains taking the characters where they seemingly want to be. Cinematographer Lee Pingping shot Café Lumiere on location with natural sound and lighting; his camera often lingers statically on a scene as the characters walk in and out of the carefully composed frame and are heard off-screen, in long takes, furthering the illusion of reality — mimicking the truth Ozu strove for in his work. In essence, the film has no beginning, no middle, and no end; it is 104 dazzling minutes in the life of a fascinating woman and her friends and relatives. Café Lumiere is screening December 4 at 4:30 and December 6 at 7:30 as part of the Film Society of Lincoln Center festival “Ozu and His Afterlives,” which honors the 110th anniversary of the master filmmaker’s birth and the 50th anniversary of his death; he died on his birthday at the age of sixty in 1963. The series features Ozu’s An Autumn Afternoon and Equinox Flower in addition to seven works that were either directly or indirectly inspired by Ozu and his unique style, including Hirokazu Kore-eda’s Still Walking, Jim Jarmusch’s Stranger Than Paradise, Aki Kaurismäki’s The Match Factory Girl, Claire Denis’s 35 Shots of Rum, Pedro Costa’s In Vanda’s Room, and Wim Wenders’s Tokyo-Ga.