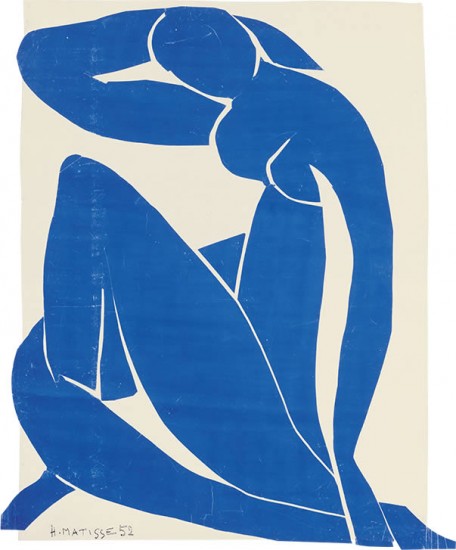

Henri Matisse, “Blue Nude,” gouache on paper, cut and pasted, mounted on canvas, spring 1952 (Musée national d’art moderne/Centre de création industrielle, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris)

Museum of Modern Art

The Joan and Preston Robert Tisch Exhibition Gallery, sixth floor

11 West 53rd St. between Fifth & Sixth Aves.

Timed tickets daily through February 10, $25

212-708-9400

www.moma.org

Near the center of “Henri Matisse: The Cut-Outs,” visitors gather to watch excerpts from Frédéric Rossif’s 1950 Matisse film, which show the white-bearded artist at work, creating masterpieces with only painted paper and a pair of scissors. There’s a smile on everyone’s face as the eighty-year-old Matisse cuts shapes out of yellow paper, perhaps a bit more sophisticated than a young child making a row of paper dolls. And that gets right to the heart of why the exhibition is so successful, and why Matisse’s cut-outs are so beloved: It seems so simple, something that anyone can do, but of course that is not quite true, as no one has ever used a pair of scissors quite like Matisse did. In her catalog essay “Bodies and Waves,” Jodi Hauptman discusses Matisse’s methods when beginning his first “Blue Nude.” She writes, “The process was arduous. Matisse labored for a number of weeks, relentlessly revising. His studio assistant at the time, Paule Martin, pushed by Matisse to work with equal rigor, describes the tense conditions: ‘Whereas subsequent forms were cut in a single movement, the first figure demanded such patience and attention on Matisse’s part, but also from me, that it exhausted me and I was on the brink of collapse. He made me pin tiny squares of paper to enhance the curvature of the thigh or some other part of the body, then remove parts of the figure to remove colour strips, then set it back in place as my febrile fingers fumbled with the pins.’ These enhancements and removals along with markings in chalk can be seen in a series of black and white photographs made by [secretary and studio assistant] Lydia Delectorskaya to document each stage, reminding the artist where he was and where he had been in order for him to decide where to go next.” The process was so organic that Matisse used pins to place the cut-outs on the walls of his studio, moving them around in different configurations until he was ready to mount them on canvas; if you look close enough, you can still see the pinholes on these marvelous works, not quite like a child pinning them onto a board in a classroom.

Installation view, “Henri Matisse: The Cut-Outs,” with (from left) “Black Leaf on Green Background,” gouache on paper, cut and pasted, 1952; “Christmas Eve,” maquette for stained-glass window, gouache on paper, cut and pasted, mounted on board, 1952; “Black Leaf on Red Background,” gouache on paper, cut and pasted, 1952; and “Christmas Eve,” stained glass, summer-fall 1952 (photo by Jonathan Muzikar © 2014 the Museum of Modern Art)

“Matisse: The Cut-Outs” consists of some 170 cut-outs, drawings, maquettes, stained glass, photographs, screenprints, illustrated books, and other ephemera related to Matisse’s use of cut paper painted over with gouache, which he began in the 1930s but became his preferred medium in the mid-to-late-1940s. This creative resurgence resulted in glorious works that combine a childlike innocence with a complex mastery of space, light, shape, and color, melding abstraction with imagery of the natural world. In “Icarus,” a maquette for the 1947 book Jazz, a silhouetted figure with a red heart floats among yellow stars. (“You have no idea how, during the cut-out paper period, the sensation of flight which emanated from me helped me better to adjust my hand when it used the scissors,” Matisse said. “It’s a kind of linear and graphic equivalence to the sensation of flight.”) Leaflike images come alive in “White Alga on Red and Green Background,” “Two Masks (The Tomato),” and “Composition with Red Cross.” A somewhat figurative element is added in “Black Boxer,” a black image over a red rectangle on a green background. Matisse displays a more spiritual side in his maquettes, studies, and trials for stained-glass windows for the Chapel of the Rosary in Vence. His four blue nudes, dating from spring 1952, are simply breathtaking, as blue geometric shapes and white spaces come together to form seated figures with slightly different body positions like a contemplative four-part dance. That summer, Matisse made the nine-panel room installation “The Swimming Pool,” an extraordinary horizontal swirl about which he said, “I have always adored the sea and now that I can no longer go for a swim, I have surrounded myself with it.” It was MoMA’s conservation of the piece that led to the idea of staging the cut-out exhibition in the first place, so now the work surrounds visitors from around the world.

An April 15, 1950, black-and-white photograph by Walter Carone shows Matisse in his bed, using a long pole to draw on the wall of his room at the Hôtel Régina in Nice with charcoal. The wall already includes elements that would become “The Thousand and One Nights.” It’s a charming photo of the artist, apparently relaxing in bed while continuing to work. Of course, just as the cut-outs themselves are not simple, neither were Matisse’s last years, much of which was spent in bed and in his wheelchair. The catalog essay “The Studio as Site and Subject” notes, “In a 1952 interview with the writer André Verdet, Henri Matisse describes a cluster of colourful cut-paper forms pinned to his studio walls as a ‘little garden.’ ‘You see,’ he explains, ‘as I am obliged to remain often in bed because of the state of my health, I have made a little garden all around me where I can walk . . . There are leaves, fruits, a bird.’ As Matisse speaks, he points to ‘a large mural composition of cut paper that encompassed half the room.’” The artist is referring to pieces that he would use to create “The Parakeet and the Mermaid,” but he could just as well be describing what visitors experience as they walk through this magical exhibition, like meandering through a colorful garden filled with joy and beauty. “Matisse: The Cut-Outs” is a revelatory show, the happiest of the season, displaying a childlike wonder as experienced by an aging yet still determined artist of extraordinary talent.

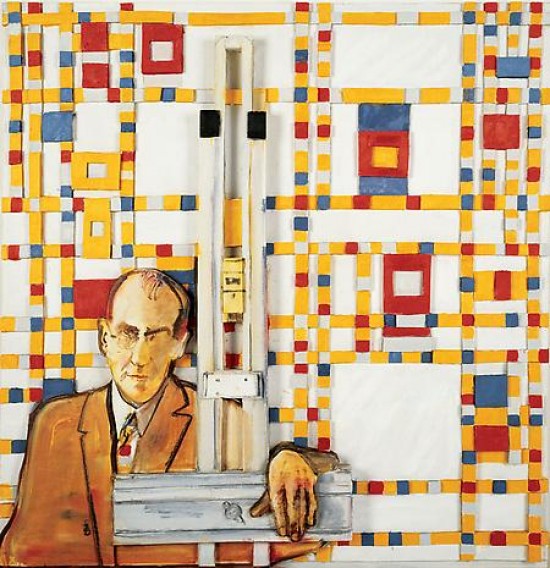

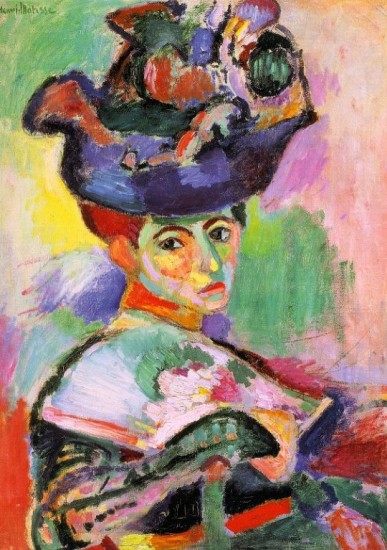

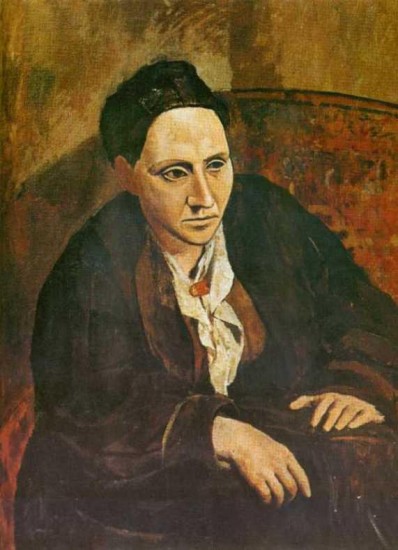

Jean-François Laguionie’s award-winning animated film, The Painting, has a very cool premise: The characters inside one of a painter’s works have organized a rigid class structure of the Alldunns, who have been completed and have sole access to the ritzy castle; the Halfies, who are not quite finished and are not allowed to join them; and the Sketchies, outlined figures who are terribly abused by the Alldunns. At the center of it all is an impossible Romeo and Juliet-like love story between the Alldunn Ramo (voiced by Adrien Larmande) and the Halfie Claire (Chloé Berthier). With the power-hungry Alldunns, led by the Great Chandelier (Jacques Roehrich), on the rampage, Ramo, the Sketchie known as Quill (Thierry Jahn), and Claire’s best friend, the Halfie Lola (Jessica Monceau), are on the run, trying to reunite the lovers and find the real-life painter so he can finish the Halfies and Sketchies and bring peace to the land. But soon they have fallen out of their painting and into the artist’s studio, where they meet characters from other works, including a reclining nude (Céline Ronte) and a self-portrait (Laguionie), and enter different canvases during their adventurous, and dangerous, search for the creator. Laguionie (Rowing Across the Atlantic, A Monkey’s Tale), who has been making animated films for five decades, has fun mimicking Modigliani, Matisse, Picasso, and other major artists, but his world-building doesn’t quite hold together as the characters continue on their colorful journey. He successfully walks that fine line between playful parable and melodramatic morality play, but things ultimately get away from him as the resolution nears. The Painting is screening December 30 at 6:15 at the IFC Center as part of the series “An Animated World: Celebrating 5 Years of GKIDS Classics,” paying tribute to GKIDS’ ongoing New York International Children’s Film Festival, which continues with such other animated works as Tono Errando, Javier Mariscal, and Fernando Trueba’s Chico & Rita, Goro Miyazaki’s From Up on Poppy Hill, and Jacques-Remy Girerd’s Mia and the Migoo.

Jean-François Laguionie’s award-winning animated film, The Painting, has a very cool premise: The characters inside one of a painter’s works have organized a rigid class structure of the Alldunns, who have been completed and have sole access to the ritzy castle; the Halfies, who are not quite finished and are not allowed to join them; and the Sketchies, outlined figures who are terribly abused by the Alldunns. At the center of it all is an impossible Romeo and Juliet-like love story between the Alldunn Ramo (voiced by Adrien Larmande) and the Halfie Claire (Chloé Berthier). With the power-hungry Alldunns, led by the Great Chandelier (Jacques Roehrich), on the rampage, Ramo, the Sketchie known as Quill (Thierry Jahn), and Claire’s best friend, the Halfie Lola (Jessica Monceau), are on the run, trying to reunite the lovers and find the real-life painter so he can finish the Halfies and Sketchies and bring peace to the land. But soon they have fallen out of their painting and into the artist’s studio, where they meet characters from other works, including a reclining nude (Céline Ronte) and a self-portrait (Laguionie), and enter different canvases during their adventurous, and dangerous, search for the creator. Laguionie (Rowing Across the Atlantic, A Monkey’s Tale), who has been making animated films for five decades, has fun mimicking Modigliani, Matisse, Picasso, and other major artists, but his world-building doesn’t quite hold together as the characters continue on their colorful journey. He successfully walks that fine line between playful parable and melodramatic morality play, but things ultimately get away from him as the resolution nears. The Painting is screening December 30 at 6:15 at the IFC Center as part of the series “An Animated World: Celebrating 5 Years of GKIDS Classics,” paying tribute to GKIDS’ ongoing New York International Children’s Film Festival, which continues with such other animated works as Tono Errando, Javier Mariscal, and Fernando Trueba’s Chico & Rita, Goro Miyazaki’s From Up on Poppy Hill, and Jacques-Remy Girerd’s Mia and the Migoo.