Tobacco-shop clerk Bertha Olsson (Mai Zetterling) is terrified of life in Alf Sjöberg’s Torment

TORMENT (FRENZY) (HETS) (Alf Sjöberg, 1944)

Film Forum

209 West Houston St.

Saturday, May 7, Monday, May 9, Friday, May 13, Tuesday, May 17

Series runs May 6-19

212-727-8110

filmforum.org

Film Forum pays tribute to Swedish actress, director, and novelist Mai Zetterling with a two-week, twenty-one-film retrospective featuring works directed by Basil Dearden, Nicolas Roeg, Ingmar Bergman, Alf Sjöberg, Christina Olofson, Ken Loach, and Zetterling, among others, ranging from 1944 to 1990. A passionate feminist, Zetterling studied at the National Theater in Sweden, became a star in England, had affairs with Herbert Lom and Tyrone Power, left Hollywood (avoiding the blacklist), and passed away in 1994 at the age of sixty-eight. “It feels like I’m a long way away from pretty much every norm there is,” she said.

One of the series highlights is Sjöberg’s intense 1944 expressionistic noir, Torment, which had its US premiere at the Museum of Modern Art in 1962. Although directed by Sjöberg, Torment, also known as Frenzy, was written by Bergman, who also served as assistant director and made his directing debut in the final scene, which Bergman added at the insistence of the producers when Sjöberg was not available. A kind of inversion of Josef von Sternberg’s The Blue Angel, the film is set in a boarding school where high school boys are preparing for their final exams and graduation. They are terrified of their sadistic Latin teacher, whom they call Caligula (Stig Järrel), a brutal man who wields a fascistic iron fist. He particularly has it out for Jan-Erik Widgren (Alf Kjellin), the son of wealthy parents (Olav Riégo and Märta Arbin) who think he should be doing better in school. One night Jan-Erik helps out a troubled woman in the street, tobacco-shop clerk Bertha Olsson (Zetterling), who is being mentally and physically tormented by an unnamed man who ends up being Caligula. The stakes get higher and the teacher becomes even harder on Jan-Erik when he finds out the young man is having an affair with the wayward woman. When tragedy strikes, Jan-Erik’s soul is in turmoil as lies, threats, and danger grow.

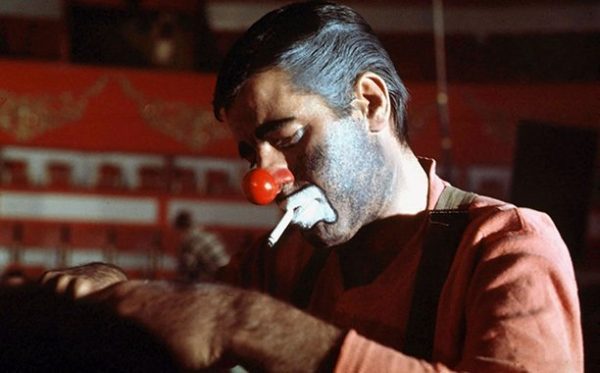

A sadistic teacher (Stig Järrel) torments a student (Alf Kjellin) in Ingmar Bergman–written Torment

The twenty-five-year-old Bergman was inspired to write his first produced film script by his experience in boarding school, which led to a public disagreement with the headmaster. In a public letter to the headmaster, Bergman explained, “I was a very lazy boy, and very scared because of my laziness, because I was involved with theater instead of school and because I hated having to be punctual, having to get up in the morning, do homework, sit still, having to carry maps, having break times, doing tests, taking oral examinations, or to put it plainly: I hated school as a principle, as a system and as an institution. And as such I have definitely not wanted to criticize my own school, but all schools.” Throughout his career, Bergman would take on institutions, including religion and marriage, but his defiance began with this hellish representation of education, which oppresses all the boys in some way, including Jan-Erik’s best friend, self-described misogynist Sandman (Stig Olin), and the geeky Pettersson (Jan Molander). While the headmaster (Olof Winnerstrand) knows how frightened the boys are of Caligula, he is willing to go only so far to protect them. The opening credits are shown over a dreamlike sequence of Jan-Erik and Bertha desperately holding on to each other, but Torment is so much more than a treacly melodrama, as if Sjöberg (Miss Julie, Ön) is setting us up for one film before switching gears into an ominous, haunting thriller.

Järrel, who played an evil, jealous teacher in his previous film, Hasse Ekman’s Flames in the Dark, is indeed scary as the devious, malicious Caligula, while adding more than a touch of sadness. Zetterling, in her breakthrough role — she would go on to star in such films as Dearden’s Frieda and Roeg’s The Witches and direct such feminist works as Loving Couples and The Girls — brings a touching vulnerability to Bertha, a young woman who can’t find happiness. It’s all anchored by Kjellin’s (Madame Bovary, Ship of Fools) central performance, so rife with emotion it evokes German silent cinema. Torment suffers from Hilding Rosenberg’s overreaching score, although it is usually offset by Martin Bodin’s cinematography, filled with lurching shadows and deep mystery. The film was produced by Victor Sjöström, the legendary director of The Phantom Carriage, The Divine Woman, The Wind, and so many others in addition to his work as an actor, starring as Professor Isak Borg in another Bergman masterpiece, 1957’s Wild Strawberries, and as the conductor in 1950’s To Joy.

“Mai Zetterling” includes such other films as Sidney Gilliat’s Only Two Can Play, Bergman’s Music in the Dark, Sjöberg’s Iris and the Lieutenant, Loach’s Hidden Agenda, and Gustaf Edgren’s Sunshine Follows Rain in addition to Zetterling’s own Loving Couples (her debut as a director), Night Games (based on her unfinished novel), We Have Many Names, The Moon Is a Green Cheese, several shorts, and other features, many in new restorations courtesy of the Swedish Film Institute. Cinema historian Jane Sloan will be at Film Forum for a Q&A following the 1:00 screening of The Girls on May 7, while avant-garde filmmaker and curator Vivian Ostrovsky will introduce the 6:10 showing of the film on May 8; in addition, actress Harriet Andersson and Kajsa Hedström of the SFI will record intros for special screenings.

Swedish director Ingmar Bergman shocked the film world in 1953 with the controversial Summer with Monika, the tale of two young lovers who run away from their families and go on a brief but intense sexual adventure. The film featured full-frontal nudity by Harriet Andersson, with whom Bergman had a short relationship; the movie was actually edited down by distributor Kroger Babb to focus on the sex and nudity, renaming it Monika, the Story of a Bad Girl! and marketing it to US audiences as an exploitation picture. But Film Forum is screening the superb original version as part of its five-week centennial celebration of Bergman’s birth. Based on the 1951 novel by Per Anders Fogelström, Summer with Monika takes place in a working-class area of Stockholm, where Harry (Lars Ekborg) and Monika (Harriet Andersson) toil away in a glassware factory. Harry lives with his ailing father (Georg Skarstedt), while Monika sleeps in her family’s kitchen. Both teens are bored with their already dull and unfulfilling lives. So when they meet in a café, the bold, forward Monika lures the shy, fragile Harry into what begins as a summer of fun, as they steal Harry’s father’s boat and head out to their own private hideaway, but ends up as something very different. Bergman boils down an entire relationship — courtship, romance, children, breakup, in a way a precursor to his later epic, Scenes from a Marriage — into ninety-seven sharp, intuitive moments, turning clichéd plot twists into subtle statements on life and family. Cinematographer Gunnar Fischer shoots the film in a dark, gloomy black-and-white, with stark close-ups — Monika stares directly into the camera at one point, challenging the audience — and long shots of water and nature, while Erik Nordgren’s score is kept spare, with Bergman favoring natural sound and light.

Swedish director Ingmar Bergman shocked the film world in 1953 with the controversial Summer with Monika, the tale of two young lovers who run away from their families and go on a brief but intense sexual adventure. The film featured full-frontal nudity by Harriet Andersson, with whom Bergman had a short relationship; the movie was actually edited down by distributor Kroger Babb to focus on the sex and nudity, renaming it Monika, the Story of a Bad Girl! and marketing it to US audiences as an exploitation picture. But Film Forum is screening the superb original version as part of its five-week centennial celebration of Bergman’s birth. Based on the 1951 novel by Per Anders Fogelström, Summer with Monika takes place in a working-class area of Stockholm, where Harry (Lars Ekborg) and Monika (Harriet Andersson) toil away in a glassware factory. Harry lives with his ailing father (Georg Skarstedt), while Monika sleeps in her family’s kitchen. Both teens are bored with their already dull and unfulfilling lives. So when they meet in a café, the bold, forward Monika lures the shy, fragile Harry into what begins as a summer of fun, as they steal Harry’s father’s boat and head out to their own private hideaway, but ends up as something very different. Bergman boils down an entire relationship — courtship, romance, children, breakup, in a way a precursor to his later epic, Scenes from a Marriage — into ninety-seven sharp, intuitive moments, turning clichéd plot twists into subtle statements on life and family. Cinematographer Gunnar Fischer shoots the film in a dark, gloomy black-and-white, with stark close-ups — Monika stares directly into the camera at one point, challenging the audience — and long shots of water and nature, while Erik Nordgren’s score is kept spare, with Bergman favoring natural sound and light.

Ingmar Bergman’s magnificently complex 1966 avant-garde masterpiece, Persona, is not just about the relationship between an actress who has suddenly decided to stop speaking and the young nurse caring for her but about the very power of film as a narrative device able to explore and examine the psychological behavior of characters both fictional and real. Persona opens with mysterious, penetrating music by Lars Johan Werle joined by the sound and image of a movie projector as the reel counts down from ten, featuring snippets of an erect male member, a cartoon, a child’s hands, a comedic silent ghost story, a tarantula, a bleeding slaughtered lamb, and a nail being hammered through a man’s palm before the camera takes viewers inside a hospital where a boy in a bed (Jörgen Lindström) starts reading Mikhail Lermontov’s mid-nineteenth-century book A Hero of Our Time, which the author describes as “a portrait, but not of one man only. . . . You will tell me, as you have told me before, that no man can be so bad as this; and my reply will be: ‘If you believe that such persons as the villains of tragedy and romance could exist in real life, why can you not believe in the reality of Pechorin?’ . . . Is it not because there is more truth in it than may be altogether palatable to you?” That passage relates to Bergman’s oeuvre as a whole but particularly to Persona, a film about identity, storytelling, and the medium itself.

Ingmar Bergman’s magnificently complex 1966 avant-garde masterpiece, Persona, is not just about the relationship between an actress who has suddenly decided to stop speaking and the young nurse caring for her but about the very power of film as a narrative device able to explore and examine the psychological behavior of characters both fictional and real. Persona opens with mysterious, penetrating music by Lars Johan Werle joined by the sound and image of a movie projector as the reel counts down from ten, featuring snippets of an erect male member, a cartoon, a child’s hands, a comedic silent ghost story, a tarantula, a bleeding slaughtered lamb, and a nail being hammered through a man’s palm before the camera takes viewers inside a hospital where a boy in a bed (Jörgen Lindström) starts reading Mikhail Lermontov’s mid-nineteenth-century book A Hero of Our Time, which the author describes as “a portrait, but not of one man only. . . . You will tell me, as you have told me before, that no man can be so bad as this; and my reply will be: ‘If you believe that such persons as the villains of tragedy and romance could exist in real life, why can you not believe in the reality of Pechorin?’ . . . Is it not because there is more truth in it than may be altogether palatable to you?” That passage relates to Bergman’s oeuvre as a whole but particularly to Persona, a film about identity, storytelling, and the medium itself.