Documentary features hundreds of photos taken by New York City icon Bill Cunningham

THE TIMES OF BILL CUNNINGHAM (Mark Bozek, 2018)

Angelika Film Center

18 West Houston St. at Mercer St.

Opens Friday, February 14

212-995-2570

www.angelikafilmcenter.com

greenwichentertainment.com

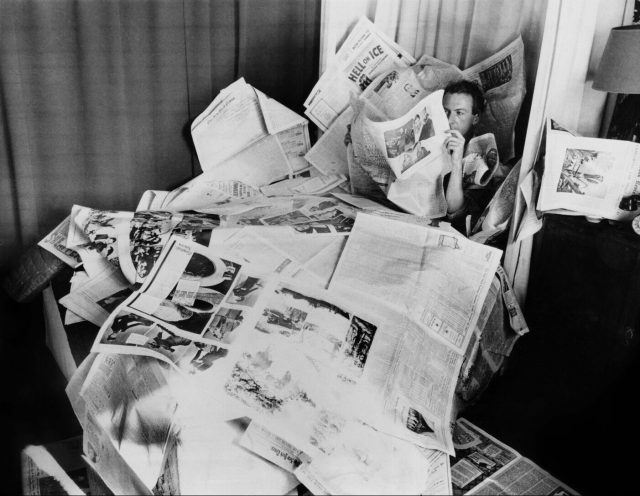

I could watch Bill Cunningham talk for hours and hours. Although we get less than an hour of him serving up delicious stories in Mark Bozek’s seventy-four-minute documentary, The Times of Bill Cunningham, it’s time well spent. “I’m not a real photographer; I’m a fashion historian,” the beloved photographer and fashion historian says in the film, which opens February 14 at the Angelika. Bozek was scheduled to speak with the Boston-born Cunningham for ten minutes in 1994, shortly after the longtime Manhattan transplant had been hit by a truck while riding his bicycle, but Cunningham just kept sharing fab tales, literally until the tape ran out. An engaging, self-effacing raconteur, Cunningham traces his career, from working at Bonwit Teller first in Massachusetts, then in New York; running his own millinery shop, William J., where he provided chapeaux to a ritzy clientele; then working at Chez Ninon before becoming a photojournalist for Women’s Wear Daily and, from 1978 to 2016, for the New York Times, most famously with his popular “On the Street” column. He didn’t set out to take pictures; his life changed when his good friend, designer Antonio Lopez, gave him a 1967 black-and-white Olympus camera.

Throughout the interview, which lasted six hours, Cunningham is shot from the mid-body up, looking slightly off camera at Bozek as he discusses attending such fashion shows as Versailles ’73; meeting such luminaries as Diana Vreeland, John Fairchild, Stephen Burrows, Brooke Astor, Marlon Brando, Anna Wintour, and Bethann Hardison; learning his trade from such other photographers as Weegee and Harold Chapman; and dyeing the dress Jackie Kennedy wore at her husband’s state funeral. He also talks about living for half a century at Carnegie Hall Studios, utterly content even though he doesn’t have his own bathroom there; in addition, despite having taken millions of photographs of fashion folk, the rich and the powerful, and, primarily, people on the street, he doesn’t care very much what he wears himself, often depending on hand-me-downs from friends and relatives. “I know I should care more how I look, but it’s more important I go out and get the right picture. That’s the main thing,” he explains.

Cunningham makes it very clear that it is what his subjects are wearing that attracts him, not their celebrity status. In fact, he took the photo that launched his Times career, a candid shot of an unsuspecting Greta Garbo on the sidewalk, because of how she was dressed; he had no idea it was Garbo until someone told him later. “It makes people feel good,” he says of the attraction of being fashionable. “They get dressed to go out in the morning — I don’t care who you are, it lifts the spirits, it’s self-esteem. . . . As long as there are human beings, there will be fashion, because people want to feel good about themselves.” As happy as he is through most of the film, his big teeth and infectious smile dominating the screen, at one point he does turn sad and emotional, thinking about the impact of the AIDS crisis, which was so dire in 1994.

Bozek might not be the best interviewer — this is his directorial debut, having previously studied acting with Lee Strasberg, worked in marketing for WilliWear, then spent more than two decades as a home-shopping pioneer (he was portrayed by Bradley Cooper in Joy) — and his camera is fairly static, but he and editor Amina Megalli let Cunningham regale us while interweaving hundreds of never-before-seen photographs taken by Cunningham from throughout his career, along with shots of Cunningham from the 1950s to just a handful of years ago, when he could still be seen riding his bike in the city. (It’s somewhat hard to fathom that Bozek had forgotten about the footage he shot in 1994 until hearing of Cunningham’s death in 2016.)

Sex and the City fashion plate Sarah Jessica Parker adds fairly standard voiceover narration that is not quite revelatory but moves the story forward, while the soundtrack features numerous songs by Moby. The Times of Bill Cunningham is very different from Richard Press’s 2011 documentary Bill Cunningham New York, in which dozens of celebrities sang Cunningham’s praises; here’s it’s just the thoroughly charming Cunningham himself, raw and uncensored, accompanied by his photographs, his passion, his visual love letter to the city and the people who live, work, and play there. “The streets are reflecting precisely what’s going on in the political world, in the social upheaval of our times,” he says. “It’s all right there.” Bozek will participate in a pair of Q&As opening weekend at the Angelika, following the 7:45 screenings Friday night with André Leon Talley and Saturday night with Hardison.

Love, Cecil is a refreshing, invigorating documentary about Oscar- and Tony-winning fashion and war photographer, diarist, production designer, painter, portraitist, costume designer, illustrator, and one of the most influential dandies of the twentieth century, Sir Cecil Beaton. Writer-director Lisa Immordino Vreeland has followed up her first two feature-length films,

Love, Cecil is a refreshing, invigorating documentary about Oscar- and Tony-winning fashion and war photographer, diarist, production designer, painter, portraitist, costume designer, illustrator, and one of the most influential dandies of the twentieth century, Sir Cecil Beaton. Writer-director Lisa Immordino Vreeland has followed up her first two feature-length films,

Greta Garbo laughs — and says she doesn’t want to be alone — in Ernst Lubitsch’s magnificent pre-Cold War comedy Ninotchka, which is being shown October 3-5 in a DCP projection as part of the IFC Center Weekend Classics series “1939 — Hollywood’s Golden Year.” In her next-to-last film, Garbo is sensational as Nina Ivanovna “Ninotchka” Yakushova, a Russian envoy sent to Paris to clean up a mess left by three comrade stooges, Iranov (Sig Ruman), Buljanov (Felix Bressart), and Kopalsky (Alexander Granach). The hapless trio from the Russian Trade Board had been sent to France to sell jewelry previously owned by the Grand Duchess Swana (Ina Claire) and now in the possession of the government following the 1917 Russian Revolution. But the duchess’s lover, Count Léon d’Algout (Melvyn Douglas), gets wind of the plan and attempts to break up the deal while also introducing the three men to the many decadent pleasures of a free, capitalist society. Then in waltzes the stern, by-the-book Ninotchka, who wants to set the Russian men straight, as well as Léon. “As basic material, you may not be bad,” she tells him atop the Eiffel Tower, “but you are the unfortunate product of a doomed culture.” At first, Ninotchka speaks robotically, spouting the company line, but she loosens up considerably once Léon shows her what communism has been depriving her of, yet it’s difficult for her to turn her back on the cause, leading to numerous hysterical conversations — the razor-sharp script was written by Charles Brackett, Walter Reisch, and Billy Wilder, based on a story by Melchior Lengyel — that serve as both a battle of the sexes and social commentary on the Russian and French ways of life. “I’ve heard of the arrogant male in capitalistic society. It is having a superior earning power that makes you that way,” Ninotchka tells Léon shortly after meeting him on a Paris street. “A Russian! I love Russians! Comrade, I’ve been fascinated by your Five-Year Plan for the last fifteen years,” Léon responds, to which Ninotchka tersely replies, “Your type will soon be extinct.” Nominated for four Academy Awards, including Best Picture, Best Actress, Best Original Story, and Best Screenplay, Ninotchka is one of the most delightful romantic comedies ever made, filled with little surprises every step of the way (including a serious cameo by Bela Lugosi), serving up a blueprint that has been followed by so many films for three-quarters of a century ever since. The IFC Center series celebrating Hollywood’s most spectacular year continues through November 9 with such other splendid fare as Wuthering Heights, The Wizard of Oz, and Gone with the Wind.

Greta Garbo laughs — and says she doesn’t want to be alone — in Ernst Lubitsch’s magnificent pre-Cold War comedy Ninotchka, which is being shown October 3-5 in a DCP projection as part of the IFC Center Weekend Classics series “1939 — Hollywood’s Golden Year.” In her next-to-last film, Garbo is sensational as Nina Ivanovna “Ninotchka” Yakushova, a Russian envoy sent to Paris to clean up a mess left by three comrade stooges, Iranov (Sig Ruman), Buljanov (Felix Bressart), and Kopalsky (Alexander Granach). The hapless trio from the Russian Trade Board had been sent to France to sell jewelry previously owned by the Grand Duchess Swana (Ina Claire) and now in the possession of the government following the 1917 Russian Revolution. But the duchess’s lover, Count Léon d’Algout (Melvyn Douglas), gets wind of the plan and attempts to break up the deal while also introducing the three men to the many decadent pleasures of a free, capitalist society. Then in waltzes the stern, by-the-book Ninotchka, who wants to set the Russian men straight, as well as Léon. “As basic material, you may not be bad,” she tells him atop the Eiffel Tower, “but you are the unfortunate product of a doomed culture.” At first, Ninotchka speaks robotically, spouting the company line, but she loosens up considerably once Léon shows her what communism has been depriving her of, yet it’s difficult for her to turn her back on the cause, leading to numerous hysterical conversations — the razor-sharp script was written by Charles Brackett, Walter Reisch, and Billy Wilder, based on a story by Melchior Lengyel — that serve as both a battle of the sexes and social commentary on the Russian and French ways of life. “I’ve heard of the arrogant male in capitalistic society. It is having a superior earning power that makes you that way,” Ninotchka tells Léon shortly after meeting him on a Paris street. “A Russian! I love Russians! Comrade, I’ve been fascinated by your Five-Year Plan for the last fifteen years,” Léon responds, to which Ninotchka tersely replies, “Your type will soon be extinct.” Nominated for four Academy Awards, including Best Picture, Best Actress, Best Original Story, and Best Screenplay, Ninotchka is one of the most delightful romantic comedies ever made, filled with little surprises every step of the way (including a serious cameo by Bela Lugosi), serving up a blueprint that has been followed by so many films for three-quarters of a century ever since. The IFC Center series celebrating Hollywood’s most spectacular year continues through November 9 with such other splendid fare as Wuthering Heights, The Wizard of Oz, and Gone with the Wind.