Hans Haacke’s 2014 Gift Horse is centerpiece of first museum survey in more than thirty years (photo by twi-ny/mdr)

New Museum of Contemporary Art

235 Bowery at Prince St.

Tuesday through Sunday through January 26, $12-$18

212-219-1222

www.newmuseum.org

In 1986, the New Museum held the survey “Hans Haacke: Unfinished Business”; more than thirty-three years later, its follow-up, “Hans Haacke: All Connected,” which runs through January 26, reveals that the German-born longtime New Yorker is still hard at work with lots on his mind. “‘Artists,’ as much as their supporters and their enemies, no matter of what ideological coloration, are unwitting partners in the art-syndrome and relate to each other dialectically,” Haacke wrote in 1974. “They participate jointly in the maintenance and/or development of the ideological make-up of their society. They work within that frame, set the frame and are being framed.” The retrospective takes up nearly the entire museum, long since moved from its much smaller 1980s Bowery location, from the lobby to the fifth floor, and comes along at just the right moment; several artists recently threatened to refuse to allow their work to appear in the Whitney Biennial due to the corporate activity of a member of its board of directors, while other artists will not participate in arts institutions that accept money from the Sacklers and other billionaire families who made their fortune in controversial industries. The now-eighty-three-year-old Haacke was well ahead of them; in 1971, his solo show at the Guggenheim was canceled because it revealed questionable financial ties between museum trustees and the art world. One of those works, Shapolsky et al. Manhattan Real Estate Holdings, a Real-Time Social System, as of May 1, 1971, which uses text and images to document the holdings of a slum landlord, is part of “All Connected,” which is populated by works Haacke has created for more than a half a century, pieces that uncover sociopolitical links between art and commerce, class, corporations, and the environment through photography, sculpture, and installation.

State of the Union, A Breed Apart, and News explore ideas of systems, organizations, and information (photo by twi-ny/mdr)

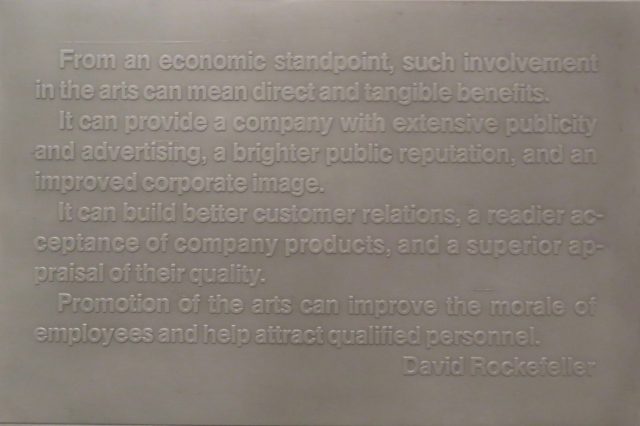

Gallery-Goers’ Birthplace and Residence Profile, Part 1 tracks where visitors to his November 1969 exhibit at Howard Wise Gallery resided; attendees of “All Connected” can share some of their personal data in New Museum Visitors Poll on the fifth floor. Politics takes center stage in works depicting Ronald Reagan, Margaret Thatcher, the American flag, George H. W. and Barbara Bush, and the Bundestag. A Breed Apart consists of Leyland Vehicles ads for Jaguar and Land-Rover with photos and statements that raise issues of racism and colonialism. In a similar vein, Thank You, Paine Webber uses the broker’s catchphrase to go inside the company’s business culture. “After thirty years, Thank You, Paine Webber gained an unfortunate new topicality,” Haacke writes on the accompanying label. “While much had changed, we were rudely reminded that much is still the way it was then. The exploitation of people’s misery — in this particular case, for PR purposes, but indicative of corporate attitudes and behavior more generally — continues unabated.” Seurat’s “Les Poseuses” (small version) traces the ownership of Georges-Pierre Seurat’s 1888 painting Les Poseuses, which started out as a gift and eventually was sold at auction for more than a million dollars in 1970. And On Social Grease comprises six photo-engraved magnesium plates that display quotes about corporate art ownership from a media executive, bank chairmen, and a politician. “From an economic standpoint, such involvement in the arts can mean direct and tangible benefits,” David Rockefeller is quoted on one of the plaques. “It can provide a company with extensive publicity and advertising, a brighter public reputation, and an improved corporate image.”

The second floor is an environmental wonderland of kinetic sculpture involving earth, air, fire, and water. Condensation Cube creates its own liquid ecosystem, complete with rainbows. Fans propel Blue Sail, White Waving Line, and Sphere in Oblique Air Jet. A small spark makes its way down High Voltage Discharge Traveling. Water sloshes in Large Water Level and Wave and freezes in Floating Ice Ring and Ice Stick. And Grass Grows is a large clump of dirt, right on the floor, that indeed has grass growing on it. In a catalog interview, Haacke talks about a shift that occurred in 1968. “I realized that my work did not address the fraught social and political world in which we lived. It was an incident that made me understand that, in addition to what I had called physical and biological systems, there are also social systems and that art is an integral part of the universe of social systems. The present debate over climate change is a perfect example of the interconnectedness of the physical, biological, and social.”

Detail, On Social Grease, six photo-engraved magnesium plates mounted on aluminum, 1975 (photo by twi-ny/mdr)

The showpiece of the exhibit is Haacke’s 2014 Gift Horse, a large-scale sculpture, designed for Trafalgar Square, of the skeleton of a horse mounted on a plinth. An electronic bow around its frontal thighbone transmits a live digital printout of the FTSE 100 ticker of the New York Stock Exchange. In the catalog, which includes contributions from Olafur Eliasson, Carsten Höller, Park McArthur, Sharon Hayes, Daniel Buren, Andrea Fraser, Thomas Hirschhorn, Walid Raad, Tania Bruguera, and others, Haacke talks about Boris Johnson’s reaction to Gift Horse. “I heard him say that the skeleton of the horse reminded him of the London subway system’s need for urgent repair. People were rolling their eyes,” he tells exhibition curators Gary Carrion-Murayari and Massimiliano Gioni. “I was standing behind him when he was spouting these lines and took a close-up photograph of his hair. The Brexiteer’s hair matches that of Donald Trump.” And let’s leave it at that.