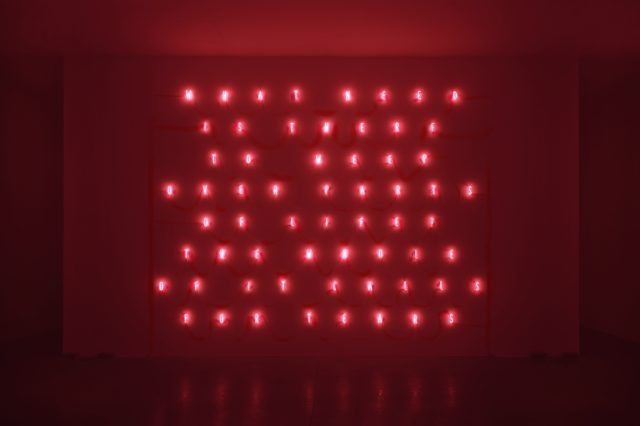

Rashid Johnson’s Antoine’s Organ is an audiovisual multimedia marvel (photo by twi-ny/mdr)

New Museum of Contemporary Art

235 Bowery at Prince St.

Tuesday through Sunday through June 6, $12-$18

212-219-1222

www.newmuseum.org

The New Museum’s “Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America,” which opened in February and closes June 6, was conceived well before the Covid-19 crisis and the filmed murder of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police, but its depiction of collective pain and call for change is both timeless and of this very moment. Most of the works, by thirty-seven Black artists, were created in the last twenty years, though a few go back as far as the 1960s, during the civil rights movement that was the precursor to the BLM protests. The heartache and agony, filtered through hope and redemption, are so palpable that as we go through the four floors, we are also overcome by sorrow for exhibition curator Okwui Enwezor, who died in March 2019 at the age of fifty-five; the show was completed in his honor by advisors Naomi Beckwith, Massimiliano Gioni, Glenn Ligon, and Mark Nash. Enwezor planned for “Grief and Grievance” to open just prior to the 2020 presidential election, as a public statement against Donald Trump, but the pandemic lockdown made that an impossibility.

“The crystallization of black grief in the face of a politically orchestrated white grievance represents the fulcrum of this exhibition. The exhibition is devoted to examining modes of representation in different mediums where artists have addressed the concept of mourning, commemoration, and loss as a direct response to the national emergency of black grief,” he writes in the catalog introduction. “With the media’s normalization of white nationalism, recent years have made clear that there is a new urgency to assess the role that artists, through works of art, have played to illuminate the searing contours of the American body politic.”

Adam Pendleton’s As Heavy as Sculpture welcomes visitors in the lobby (photo by twi-ny/mdr)

The show is among the most memorable I’ve experienced, monumental in scope yet attuned to critical details. The works, from sculpture, painting, and drawing to video, photography, and installation, demand your attention; they feel like living and breathing objects staring right into your eyes, making us all complicit. That is precisely the case with Queens-born Dawoud Bey’s archival pigment prints from his 2012 “Birmingham Project” series, black-and-white diptychs that pair a child the same age as one of the four Black girls killed in the 1963 KKK bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Alabama and the two boys murdered in the aftermath with a grown woman or man the age the victims would have been in 2012 had they lived. It’s a brutal reminder of what racism continues to take away.

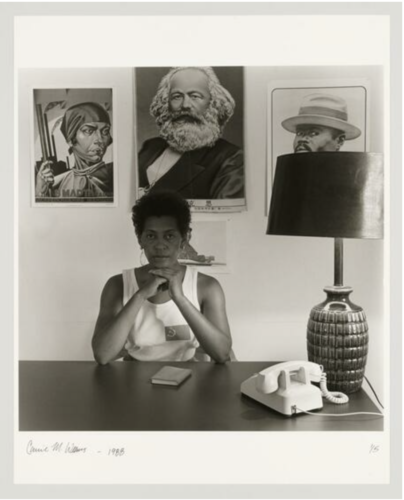

Carrie Mae Weems explores sadness and remorse in her 2008 black-and-white series “Constructing History,” which includes Mourning, a photograph of two grieving women in black sitting in chairs on a pedestal, a young girl in white grasping the knees of one of the women, evoking the Pietà.

Diamond Stingily’s Entryways is an ominous reminder of racial injustice and violence (photo by twi-ny/mdr)

Diamond Stingily’s 2016 Entryways are freestanding doors with locks, a bat leaning against each, a warning of the violence inherent in no-knock warrants and how one can be wrongly targeted even when home in bed. Birmingham native Kerry James Marshall’s 2015 painting Untitled (policeman) zooms in on a Black cop sitting on his police car, lost in thought, as if trapped between two disparate worlds.

In her “Notion of Family” photos from the first decade of this century, LaToya Ruby Frazier reveals three generations of women battling racial income inequality in the fading steel town of Braddock, Pennsylvania, where her grandmother, her mother, and she are suffering from illnesses that might have been caused by the factories. In one picture, her grandmother is cradling two babies that are actually dolls; in another, Frazier’s mother is holding tightly to a man, “Mr. Art,” staring at the viewer, implicating us in their uncertain, imminent future. Nari Ward’s 1995 Peace Keeper, re-created for this show, offers that possible future with a caged hearse that has been tarred and feathered, dozens of mufflers above and below the car as if surrounded by silence.

In Theaster Gates’s 2014 six-and-a-half-minute video Gone are the Days of Shelter and Martyr, the Black Monks of Mississippi turn over and slam unhinged doors in the ruins of the Roman Catholic Church of St. Laurence on the South Side, where Gates is from and sang in a choir. The defiance inherent in the loud bangs is like beating hearts proclaiming they will never give up.

“Something’s wrong here,” a Black man says to a news reporter at the beginning of Arthur Jafa’s 2016 video Love Is the Message, the Message Is, seven and a half minutes of archival clips of music and dancing, body-camera footage of police stops, Michael Jackson, Hurricane Katrina, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., racist silent movies, a city burning, Miles Davis, Black cowboys, Serena Williams, and a young boy crying, set to Kanye West’s “Ultralight Beam.” Dance and choreography are at the center of Okwui Okpokwasili’s 2017 Poor People’s TV Room (Solo), a multimedia installation that references the Women’s War of 1929 in Nigeria and the April 2014 Boko Haram kidnappings of 276 Christian schoolgirls in Chibok; if you arrive at the right time, Okpokwasili might be dancing live inside.

Nari Ward’s powerful Peace Keeper has been re-created for this exhibition (photo by twi-ny/mdr)

The exhibit also features compelling works from Tiona Nekkia McClodden, Julie Mehretu, Oscar nominee Garrett Bradley, Melvin Edwards, Daniel LaRue Johnson, Terry Adkins, Adam Pendleton, and others. The piece that might stay with you the longest is Rashid Johnson’s 2016 Antoine’s Organ, a massive autobiographical installation constructed of black steel scaffolding, grow lights, living plants in handmade pots, skulls, wood, black soap and shea butter, rugs, monitors playing some of Johnson’s short films, books (Ta-Nehisi Coates’s Between the World and Me, Paul Beatty’s The Sellout, Randall Kennedy’s Sellout: The Politics of Racial Betrayal, a twelve-step tome that references Johnson’s sobriety), and a piano in the middle on which, at times, Antoine “AudioBLK” Baldwin performs original jazz compositions. I first saw the piece five years ago at Johnson’s “Fly Away” show at Hauser & Wirth in Chelsea, but the socially conscious ecosystem takes on a new dimension here, containing an ever-expanding Black culture that has been through so much these last five years since it was first displayed.

“Grief and Grievance” — supplemented by a series of live conversations with such participating artists as Howardena Pindell, Kevin Beasley, Jennie Jones, Hank Willis Thomas, Okpokwasili, Edwards, Johnson, McClodden, Bey, Marshall, Frazier, and Gates (which can be viewed here) — is an eye-opening, must-see show that has the potential to deeply affect the way you see America today.