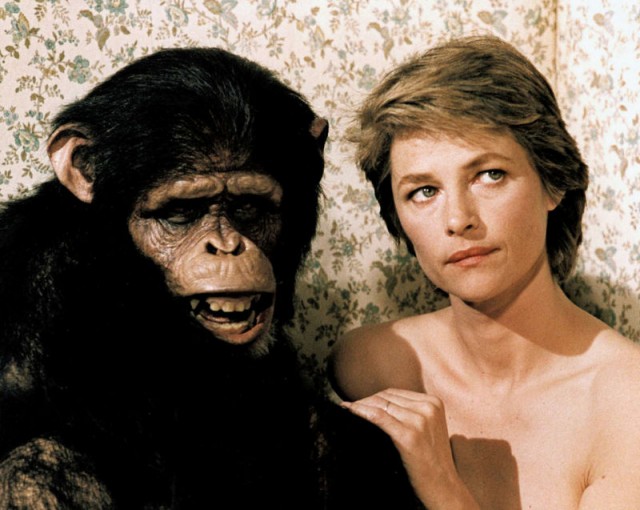

Married mother Margaret Jones (Charlotte Rampling) is madly in love with a monkey in Nagisa Ôshima’s surprisingly tame MAX, MON AMOUR

CinéSalon: MAX, MON AMOUR (Nagisa Ôshima, 1986)

French Institute Alliance Française, Florence Gould Hall

55 East 59th St. between Madison & Park Aves.

Tuesday, July 7, $13, 4:00 & 7:30

Series continues Tuesdays through July 28

212-355-6100

fiaf.org

It’s rather hard to tell how much Japanese auteur Nagisa Ôshima is monkeying around with his very strange 1986 movie, Max, Mon Amour, a love story between an intelligent, beautiful woman and a chimpanzee. The director of such powerful films as Cruel Story of Youth; Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence; Taboo; and In the Realm of the Senses seems to have lost his own senses with this surprisingly straightforward, tame tale of bestiality, a collaboration with master cinematographer Raoul Coutard, who shot seminal works by Truffaut and Godard; screenwriter Jean-Claude Carrière, who has written or cowritten nearly ninety films by such directors as Pierre Étaix (who plays the detective in Max), Luis Buñuel, Volker Schlöndorff, Philippe Garrel, and Miloš Forman; and special effects and makeup artist extraordinaire Rick Baker, the mastermind behind the 1976 King Kong, the Michael Jackson video Thriller, Ratboy, Hellboy, and An American Werewolf in London, among many others. Evoking Bedtime for Bonzo and Ed more than Planet of the Apes and Gorillas in the Mist, Max, Mon Amour is about a well-to-do English family living in Paris whose lives undergo a rather radical change when husband Peter Jones (Anthony Higgins) catches his elegant wife, Margaret (Charlotte Rampling), in bed with a chimp. Margaret insists that she and the chimp, Max, are madly in love and somehow convinces Peter to let her bring the sensitive yet dangerous beast home, which confuses their son, Nelson (Christopher Hovik), and causes their maid, Maria (Victoria Abril), to break out in ugly rashes. Peter, a diplomat, works for the queen of England, so as he prepares for a royal visit to Paris, he also has to deal with this new addition to his ever-more-dysfunctional family.

It’s rather hard to tell how much Japanese auteur Nagisa Ôshima is monkeying around with his very strange 1986 movie, Max, Mon Amour, a love story between an intelligent, beautiful woman and a chimpanzee. The director of such powerful films as Cruel Story of Youth; Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence; Taboo; and In the Realm of the Senses seems to have lost his own senses with this surprisingly straightforward, tame tale of bestiality, a collaboration with master cinematographer Raoul Coutard, who shot seminal works by Truffaut and Godard; screenwriter Jean-Claude Carrière, who has written or cowritten nearly ninety films by such directors as Pierre Étaix (who plays the detective in Max), Luis Buñuel, Volker Schlöndorff, Philippe Garrel, and Miloš Forman; and special effects and makeup artist extraordinaire Rick Baker, the mastermind behind the 1976 King Kong, the Michael Jackson video Thriller, Ratboy, Hellboy, and An American Werewolf in London, among many others. Evoking Bedtime for Bonzo and Ed more than Planet of the Apes and Gorillas in the Mist, Max, Mon Amour is about a well-to-do English family living in Paris whose lives undergo a rather radical change when husband Peter Jones (Anthony Higgins) catches his elegant wife, Margaret (Charlotte Rampling), in bed with a chimp. Margaret insists that she and the chimp, Max, are madly in love and somehow convinces Peter to let her bring the sensitive yet dangerous beast home, which confuses their son, Nelson (Christopher Hovik), and causes their maid, Maria (Victoria Abril), to break out in ugly rashes. Peter, a diplomat, works for the queen of England, so as he prepares for a royal visit to Paris, he also has to deal with this new addition to his ever-more-dysfunctional family.

Throughout the film, it’s almost impossible to figure out when Ôshima is being serious, when he is being ironic, when he is trying to make a metaphorical point about evolution, or when he is commenting on the state of contemporary aristocratic European society. When Margaret puts on a fur coat, is that a reference to her hypocrisy? Is her affair with a zoo animal being directly compared to Peter’s dalliance with his assistant Camille (Diana Quick)? Even better, is Ôshima relating Max to Her Royal Highness? We are all mammals, after all. Or are Ôshima and Carrière merely riffing on Buñuel’s 1972 surrealist classic The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, which Carrière cowrote? Perhaps Max, Mon Amour is about all of that, or maybe none of it, as Ôshima lays it all out very plainly, as if it is not a completely crazy thing that a woman can have an affair with a chimp and have him become part of the family. Regardless, the film is just plain silly, although it looks pretty great, particularly Rampling wearing gorgeous outfits and a Princess Di do and Quick in hysterically hideous haute couture gone terribly wrong. Meanwhile, Michel Portal’s score mines Laurie Anderson territory. You can decide for yourself whether Max, Mon Amour is a misunderstood masterpiece or an absurd piece of trifle when it is shown on July 7 in the French Institute Alliance Française’s CinéSalon series “Jean-Claude Carrière: Writing the Impossible.” (The 7:30 show will be introduced by Japan Society film programmer Kazu Watanabe, who will attempt to shed more light on this, and both the 4:00 and 7:30 shows will be followed by a wine reception.) The two-month festival consists of a wide range of films written by two-time Oscar winner Carrière, who, at eighty-three, is still hard at work. The series continues through July 28 with such other Carrière collaborations as Andrzej Wajda’s Danton, Louis Malle’s May Fools, and Jonathan Glazer’s Birth.

In 1980, Jean-Luc Godard told journalist Jonathan Cott, “When you have a first love, a first experience, a first movie, once you’ve done it, you can’t repeat it,” the French auteur said about his latest film, Every Man for Himself, which he considered his “second first” film. “If it’s bad, it’s a repetition; if it’s good, it’s a spiral. It’s like when you return home — to mountains and lakes, in my case — you have a feeling of childhood, of beginning again. But in films, it’s very seldom that you have the opportunity to make your first film for the second time.” For Godard, whose real first film was 1960’s Breathless and who went on to make such other avant-garde masterworks as Contempt, Pierrot le Fou, Masculine Feminine, and Two or Three Things I Know About Her, Every Man for Himself might have been somewhat of a return to narrative, but only as Godard can do it. He still plays with form and various technological aspects, including a fascination with slow motion and an unusual, often very funny use of incidental music, and his manner of episodic storytelling would not exactly be called traditional. Sometimes it’s good, and sometimes it’s bad. Jacques Dutronc stars as mean-spirited, self-obsessed Swiss television director Paul Godard, who has recently broken up with his girlfriend, Denise Rimbaud (Nathalie Baye), who wants to leave their apartment in the city for the idyllic greenery of the country. (Yes, the characters have such names as Godard and Rimbaud, and the voice of Marguerite Duras shows up.) Paul then meets a prostitute, Isabelle Rivière (Isabelle Huppert), who is interested in Paul and Denise’s apartment, planning on bettering her life even as she still must submit to the whims of her clients, including a businessman who orchestrates a strange orgy that would make Secretary’s James Spader proud.

In 1980, Jean-Luc Godard told journalist Jonathan Cott, “When you have a first love, a first experience, a first movie, once you’ve done it, you can’t repeat it,” the French auteur said about his latest film, Every Man for Himself, which he considered his “second first” film. “If it’s bad, it’s a repetition; if it’s good, it’s a spiral. It’s like when you return home — to mountains and lakes, in my case — you have a feeling of childhood, of beginning again. But in films, it’s very seldom that you have the opportunity to make your first film for the second time.” For Godard, whose real first film was 1960’s Breathless and who went on to make such other avant-garde masterworks as Contempt, Pierrot le Fou, Masculine Feminine, and Two or Three Things I Know About Her, Every Man for Himself might have been somewhat of a return to narrative, but only as Godard can do it. He still plays with form and various technological aspects, including a fascination with slow motion and an unusual, often very funny use of incidental music, and his manner of episodic storytelling would not exactly be called traditional. Sometimes it’s good, and sometimes it’s bad. Jacques Dutronc stars as mean-spirited, self-obsessed Swiss television director Paul Godard, who has recently broken up with his girlfriend, Denise Rimbaud (Nathalie Baye), who wants to leave their apartment in the city for the idyllic greenery of the country. (Yes, the characters have such names as Godard and Rimbaud, and the voice of Marguerite Duras shows up.) Paul then meets a prostitute, Isabelle Rivière (Isabelle Huppert), who is interested in Paul and Denise’s apartment, planning on bettering her life even as she still must submit to the whims of her clients, including a businessman who orchestrates a strange orgy that would make Secretary’s James Spader proud.

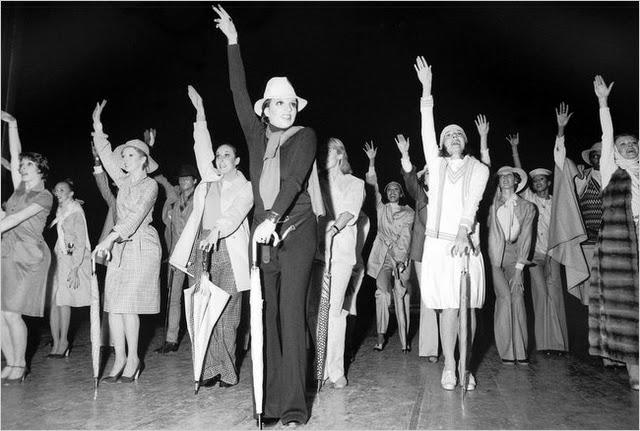

The French Institute Alliance Française’s CinéSalon series “Haute Couture on Film,” part of the larger “Fashion at FIAF” festival, comes to a fitting close with Deborah Riley Draper’s fab 2012 doc, Versailles ’73: American Runway Revolution. In June 1919, Germany and the Allies signed a peace treaty at the palace of Versailles in France, where Louis XIV and his family lived until they had to flee in 1789. Nearly two hundred years later, the historic Château de Versailles was in disrepair, and American fashion doyenne Eleanor Lambert decided to do something about it, creating a high-society fundraiser featuring presentations by five French designers and five American designers. Deborah Riley Draper captures all of the backstage intrigue and surprising results in her debut full-length film, speaking with many of those who were on hand for what turned out to be an eye-opening, game-changing haute couture competition. “There are moments in history that change the course of history,” says Versailles ’73 model Alva Chinn. “That was a moment in history that changed the course of fashion history.” Among those sharing their perspectives on the Battle of Versailles, which pitted Yves Saint Laurent, Christian Dior, Hubert de Givenchy, Pierre Cardin, and Emanuel Ungaro against Anne Klein, Stephen Burrows, Bill Blass, Oscar de la Renta, and Halston, are Met Costume Institute curator-in-charge Harold Koda, Chambre Syndicale de la Haute Couture president Didier Grumbach, American actor and Halston assistant Dennis Christopher (Breaking Away), Château de Versailles chief curator Beatrix Saule, public relations executive and former Lambert assistant John Tiffany, Versailles ’73 patron Simone Levitt, former Halston assistant and Bill Blass executive Tom Fallon, photographer Charles Tracy, designer Burrows, and, most fabulously, participating models China Machado, Barbara Jackson, Charleen Dash, Pat Cleveland, Karen Bjornsen, Norma Jean Darden, Nancy North, Marisa Berenson, Bethann Hardison, Carla LaMonte, and Billie Blair, who are utterly delightful as they detail the fascinating goings-on.

The French Institute Alliance Française’s CinéSalon series “Haute Couture on Film,” part of the larger “Fashion at FIAF” festival, comes to a fitting close with Deborah Riley Draper’s fab 2012 doc, Versailles ’73: American Runway Revolution. In June 1919, Germany and the Allies signed a peace treaty at the palace of Versailles in France, where Louis XIV and his family lived until they had to flee in 1789. Nearly two hundred years later, the historic Château de Versailles was in disrepair, and American fashion doyenne Eleanor Lambert decided to do something about it, creating a high-society fundraiser featuring presentations by five French designers and five American designers. Deborah Riley Draper captures all of the backstage intrigue and surprising results in her debut full-length film, speaking with many of those who were on hand for what turned out to be an eye-opening, game-changing haute couture competition. “There are moments in history that change the course of history,” says Versailles ’73 model Alva Chinn. “That was a moment in history that changed the course of fashion history.” Among those sharing their perspectives on the Battle of Versailles, which pitted Yves Saint Laurent, Christian Dior, Hubert de Givenchy, Pierre Cardin, and Emanuel Ungaro against Anne Klein, Stephen Burrows, Bill Blass, Oscar de la Renta, and Halston, are Met Costume Institute curator-in-charge Harold Koda, Chambre Syndicale de la Haute Couture president Didier Grumbach, American actor and Halston assistant Dennis Christopher (Breaking Away), Château de Versailles chief curator Beatrix Saule, public relations executive and former Lambert assistant John Tiffany, Versailles ’73 patron Simone Levitt, former Halston assistant and Bill Blass executive Tom Fallon, photographer Charles Tracy, designer Burrows, and, most fabulously, participating models China Machado, Barbara Jackson, Charleen Dash, Pat Cleveland, Karen Bjornsen, Norma Jean Darden, Nancy North, Marisa Berenson, Bethann Hardison, Carla LaMonte, and Billie Blair, who are utterly delightful as they detail the fascinating goings-on.

“We’ll have as much fun as we can,” Robert de la Chesnaye (Marcel Dalio) says in Jean Renoir’s 1939 comic masterpiece, the madcap farce The Rules of the Game. And oh, what fun it is. Renoir, the son of Impressionist painter Pierre-Auguste Renoir, skewers love and lust among France’s idle rich on the eve of WWII, the haute bourgeoisie fiddling in their own self-defeating way while their country is about to burn. Banned by the government for being “too demoralizing,” The Rules of the Game follows a group of men and women, both servants and masters, as they jump from bed to bed, sometimes in full view of their spouse. It’s 1939, but even with war on the horizon, a fanciful coterie of friends and acquaintances have gathered for a weekend at Château de la Colinière, the country estate owned by Robert, who is married to Christine (Nora Grégor) but has been fooling around with Geneviève de Marras (Mila Parély). Christine, meanwhile, is being wooed by aviator André Jurieux (Roland Toutain), who has just flown solo across the Atlantic, and the dapper Monsieur de St. Aubin (Pierre Nay). Newly hired domestic Marceau (Julien Carette) has the hots for Christine’s maid, Lisette (Paulette Dubost), whose extremely jealous husband, Edouard Schumacher (Gaston Modot), is Robert’s game warden, prowling the grounds with a rifle he is ready to use. And in the middle of it all is Octave (Renoir), a bear of man who is friends with André and Christine and a former lover of Lisette’s. Borrowing elements from Alfred de Musset’s Les caprices de Marianne and Pierre-Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais’s Le mariage de Figaro, Renoir depicts French society as a bunch of silly, selfish fools, and even though in the credits, over delightful music by Mozart, he calls it “A Dramatic Fantasy” that “does not claim to be a study of manners,” he later referred to it as “an exact description of the bourgeoisie of our time.” Its truthfulness is what helped make the film a critical and popular failure upon its initial release, leading Renoir to cut nearly a half hour in a desperate attempt to save it.

“We’ll have as much fun as we can,” Robert de la Chesnaye (Marcel Dalio) says in Jean Renoir’s 1939 comic masterpiece, the madcap farce The Rules of the Game. And oh, what fun it is. Renoir, the son of Impressionist painter Pierre-Auguste Renoir, skewers love and lust among France’s idle rich on the eve of WWII, the haute bourgeoisie fiddling in their own self-defeating way while their country is about to burn. Banned by the government for being “too demoralizing,” The Rules of the Game follows a group of men and women, both servants and masters, as they jump from bed to bed, sometimes in full view of their spouse. It’s 1939, but even with war on the horizon, a fanciful coterie of friends and acquaintances have gathered for a weekend at Château de la Colinière, the country estate owned by Robert, who is married to Christine (Nora Grégor) but has been fooling around with Geneviève de Marras (Mila Parély). Christine, meanwhile, is being wooed by aviator André Jurieux (Roland Toutain), who has just flown solo across the Atlantic, and the dapper Monsieur de St. Aubin (Pierre Nay). Newly hired domestic Marceau (Julien Carette) has the hots for Christine’s maid, Lisette (Paulette Dubost), whose extremely jealous husband, Edouard Schumacher (Gaston Modot), is Robert’s game warden, prowling the grounds with a rifle he is ready to use. And in the middle of it all is Octave (Renoir), a bear of man who is friends with André and Christine and a former lover of Lisette’s. Borrowing elements from Alfred de Musset’s Les caprices de Marianne and Pierre-Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais’s Le mariage de Figaro, Renoir depicts French society as a bunch of silly, selfish fools, and even though in the credits, over delightful music by Mozart, he calls it “A Dramatic Fantasy” that “does not claim to be a study of manners,” he later referred to it as “an exact description of the bourgeoisie of our time.” Its truthfulness is what helped make the film a critical and popular failure upon its initial release, leading Renoir to cut nearly a half hour in a desperate attempt to save it.