THE BLUE ROOM (LA CHAMBRE BLEUE) (Mathieu Amalric, 2014)

Film Society of Lincoln Center

Monday, September 29, Alice Tully Hall, 9:00 pm

Tuesday, September 30, Francesca Beale Theater, 9:00 pm

Festival runs September 26 – October 12

212-875-5050

www.filmlinc.com

www.lachambrebleue-lefilm.com

Real-life partners Mathieu Amalric and Stéphanie Cléau strip Georges Simenon’s short 1955 novel The Blue Room to its bare essentials — and we do mean bare — in their intimate, claustrophobic modern noir adaptation, which makes its North American premiere at the New York Film Festival September 29 and 30. In addition to being one of the world’s most talented actors, starring in such films as Kings and Queen, The Diving Bell and the Butterfly, A Christmas Tale, and Venus in Fur, Amalric has directed several previous works, including On Tour, which earned him the Best Director prize at Cannes. In The Blue Room, Amalric plays Julien Gahyde, a successful agriculture equipment salesman whose passionate affair with a local pharmacist’s wife, Esther Despierre (Cléau, who cowrote the script with Amalric), appears to have ended in murder. The film opens with Grégoire Hetzel’s lush, sweeping music as the camera makes its way to a blue hotel room where Julien and Esther have just made love offscreen. “Did I hurt you?” she asks. “No,” he responds. “You’re angry,” she says. “No,” he repeats as she laughs and a drop of blood falls on a creamy white sheet. Only then do we see the naked, sweaty couple, whose lurid tale has been succinctly revealed by this highly stylized, beautifully orchestrated scene. Next we hear Julien being interrogated by a magistrate (Laurent Poitrenaux) about a suspicious death, and soon we see Julien in handcuffs in the police station. We don’t know exactly what crime he has been accused of, nor do we know the victim — it could be Julien’s wife, Delphine (Léa Drucker), Esther’s husband, Nicolas (Olivier Mauvezin), or maybe even Esther herself. But as director Amalric, cinematographer Christophe Beaucarne, and editor François Gedigier cut between the past and the present, the details slowly unfold — although that doesn’t mean they ever become completely clear.

Real-life partners Mathieu Amalric and Stéphanie Cléau strip Georges Simenon’s short 1955 novel The Blue Room to its bare essentials — and we do mean bare — in their intimate, claustrophobic modern noir adaptation, which makes its North American premiere at the New York Film Festival September 29 and 30. In addition to being one of the world’s most talented actors, starring in such films as Kings and Queen, The Diving Bell and the Butterfly, A Christmas Tale, and Venus in Fur, Amalric has directed several previous works, including On Tour, which earned him the Best Director prize at Cannes. In The Blue Room, Amalric plays Julien Gahyde, a successful agriculture equipment salesman whose passionate affair with a local pharmacist’s wife, Esther Despierre (Cléau, who cowrote the script with Amalric), appears to have ended in murder. The film opens with Grégoire Hetzel’s lush, sweeping music as the camera makes its way to a blue hotel room where Julien and Esther have just made love offscreen. “Did I hurt you?” she asks. “No,” he responds. “You’re angry,” she says. “No,” he repeats as she laughs and a drop of blood falls on a creamy white sheet. Only then do we see the naked, sweaty couple, whose lurid tale has been succinctly revealed by this highly stylized, beautifully orchestrated scene. Next we hear Julien being interrogated by a magistrate (Laurent Poitrenaux) about a suspicious death, and soon we see Julien in handcuffs in the police station. We don’t know exactly what crime he has been accused of, nor do we know the victim — it could be Julien’s wife, Delphine (Léa Drucker), Esther’s husband, Nicolas (Olivier Mauvezin), or maybe even Esther herself. But as director Amalric, cinematographer Christophe Beaucarne, and editor François Gedigier cut between the past and the present, the details slowly unfold — although that doesn’t mean they ever become completely clear.

Amalric fills The Blue Room with bold splashes of color amid all the darkness and muted skin tones, from the red towel that signals Julien and Esther’s illicit rendezvous to Delphine’s blue bikini to the strikingly red hair of Nicolas’s mother (Véronique Alain) and the shiny green and yellow John Deere equipment he sells. Amalric and Cléau trim so much out of the original story that it too often feels overly cold and calculating, the manipulation too clear and obvious. The nudity also lacks subtlety; Amalric and Cléau might be comfortable with each other sans clothing, but it seems to be a bit of an obsession with Amalric the director. Nonetheless, The Blue Room, shot in the old-fashioned aspect ratio of 1:33 and running a mere seventy-six minutes, is a gripping yarn, a lurid tale of sex and murder, pain and passion, and femmes fatale, told from the point of view of a relatively quiet, reserved man who never thought his world could just fall apart like it does. With such plot elements as adultery and murder and even the presence of a young daughter (Mona Jaffart), the story cannot fail to call to mind French author Gustave Flaubert’s classic novel of provincial France and misplaced passion, Madame Bovary, but the near-echoes never become too loud, merely adding a somewhat puzzling flavor to the film, like a dream half remembered. Amalric will participate in a Q&A following the September 29 screening at 9:00 at Alice Tully Hall; in addition, he will sit down for a free HBO Directors Dialogue that same day at 6:00 in the Walter Reade Theater, where he’s sure to discuss such influences as Alfred Hitchcock, François Truffaut, Claude Chabrol, Otto Preminger, and Fritz Lang.

The awesomely titled Film Society of Lincoln Center complete retrospective “Fifty Years of John Waters: How Much Can You Take?” was probably primarily inspired by the fabulously titled September 11 program “Celluloid Atrocity Night!” That evening includes three of the Baltimore-born auteur’s craziest early works, hailing from 1969-70, when the King of Bad Taste, serving as writer, director, producer, cinematographer, and editor, was in his early twenties. The triple feature kicks off with the extremely low budget romp Multiple Maniacs, which begins with barker Mr. David (David Lochary) inviting people into “Lady Divine’s Cavalcade of Perversions,” proclaiming, “This is the show you want. . . . the sleaziest show on earth. Not actors, not paid imposters, but real, actual filth who have been carefully screened in order to present to you the most flagrant violation of natural law known to man.” Of course, that serves as the perfect introduction to the cinematic world of John Waters, one dominated by the celebration of sexual proclivities, fetish, salaciousness, indecency, violence, and marginalized weirdos living on the fringes of society. Lady Divine, played by Divine, turns out to be a cheat, the freak show just a set-up for a robbery. Soon Divine is jealous of David’s relationship with Bonnie (Mary Vivian Pearce), hanging out with her topless daughter, Cookie (Cookie Mueller), and being led into a church by the Infant of Prague (Michael Renner Jr.), where she’s brought to sexual ecstasy by Mink (Mink Stole). There’s also rape, murder, Jesus (George Figgs), the Virgin Mary (Edith Massey), and the famed Lobstura. Shot in lurid black-and-white, Multiple Maniacs is a divine freak show all its own, an underground classic that redefined just what a movie could be, a crude, disturbing tale that you can’t turn away from.

The awesomely titled Film Society of Lincoln Center complete retrospective “Fifty Years of John Waters: How Much Can You Take?” was probably primarily inspired by the fabulously titled September 11 program “Celluloid Atrocity Night!” That evening includes three of the Baltimore-born auteur’s craziest early works, hailing from 1969-70, when the King of Bad Taste, serving as writer, director, producer, cinematographer, and editor, was in his early twenties. The triple feature kicks off with the extremely low budget romp Multiple Maniacs, which begins with barker Mr. David (David Lochary) inviting people into “Lady Divine’s Cavalcade of Perversions,” proclaiming, “This is the show you want. . . . the sleaziest show on earth. Not actors, not paid imposters, but real, actual filth who have been carefully screened in order to present to you the most flagrant violation of natural law known to man.” Of course, that serves as the perfect introduction to the cinematic world of John Waters, one dominated by the celebration of sexual proclivities, fetish, salaciousness, indecency, violence, and marginalized weirdos living on the fringes of society. Lady Divine, played by Divine, turns out to be a cheat, the freak show just a set-up for a robbery. Soon Divine is jealous of David’s relationship with Bonnie (Mary Vivian Pearce), hanging out with her topless daughter, Cookie (Cookie Mueller), and being led into a church by the Infant of Prague (Michael Renner Jr.), where she’s brought to sexual ecstasy by Mink (Mink Stole). There’s also rape, murder, Jesus (George Figgs), the Virgin Mary (Edith Massey), and the famed Lobstura. Shot in lurid black-and-white, Multiple Maniacs is a divine freak show all its own, an underground classic that redefined just what a movie could be, a crude, disturbing tale that you can’t turn away from.

Husband-and-wife filmmakers Lucien Castaing-Taylor and Ilisa Barbash follow a flock of sheep herded by a family of Norwegian-American cowboys on their last sojourns through the public lands of Montana’s Absaroka-Beartooth Wilderness in the gorgeously photographed, surprisingly intimate, and sometimes very funny documentary Sweetgrass. In 2001, Castaing-Taylor, director of the Sensory Ethnography Lab at Harvard, and Barbash, a curator of Visual Anthropology at Harvard’s Peabody Museum, found out about the Allestad ranch, an old-fashioned, Old West group of sheepherders who still did everything by hand, including leading hundreds of sheep on a 150-mile journey into the mountains for summer pasture with only a few dogs and horses. Director Castaing-Taylor uses no voice-over narration or intertitles, instead inviting the viewer to join in the story as if in the middle of the action, offering no judgments or additional information. The film begins with shearing and feeding, then birthing and mothering, before heading out on the long, sometimes treacherous trail, especially at night, when bears and wolves sneak around, looking for food. Slowly the focus switches to the men themselves, primarily an old-time singing grizzled ranch hand and a cursing, complaining cowboy. Castaing-Taylor and Barbash spent three years with the sheepherders and in the surrounding areas, amassing more than two hundred hours of footage and making to date nine films out of their experiences, mostly shorter works to be displayed in gallery installations or for anthropological reasons; Sweetgrass is the only one that has been released theatrically, offering a fascinating look at something that is destined to soon be gone forever. Sweetgrass is screening April 17 at 6:30 in the Focus on the Sensory Ethnography Lab section of the Film Society of Lincoln Center series “Art of the Real,” held in conjunction with the Whitney Biennial, and will be followed by a Q&A with Barbash. The inaugural festival runs April 11-26, featuring more than three dozen works that push the boundaries of documentary film.

Husband-and-wife filmmakers Lucien Castaing-Taylor and Ilisa Barbash follow a flock of sheep herded by a family of Norwegian-American cowboys on their last sojourns through the public lands of Montana’s Absaroka-Beartooth Wilderness in the gorgeously photographed, surprisingly intimate, and sometimes very funny documentary Sweetgrass. In 2001, Castaing-Taylor, director of the Sensory Ethnography Lab at Harvard, and Barbash, a curator of Visual Anthropology at Harvard’s Peabody Museum, found out about the Allestad ranch, an old-fashioned, Old West group of sheepherders who still did everything by hand, including leading hundreds of sheep on a 150-mile journey into the mountains for summer pasture with only a few dogs and horses. Director Castaing-Taylor uses no voice-over narration or intertitles, instead inviting the viewer to join in the story as if in the middle of the action, offering no judgments or additional information. The film begins with shearing and feeding, then birthing and mothering, before heading out on the long, sometimes treacherous trail, especially at night, when bears and wolves sneak around, looking for food. Slowly the focus switches to the men themselves, primarily an old-time singing grizzled ranch hand and a cursing, complaining cowboy. Castaing-Taylor and Barbash spent three years with the sheepherders and in the surrounding areas, amassing more than two hundred hours of footage and making to date nine films out of their experiences, mostly shorter works to be displayed in gallery installations or for anthropological reasons; Sweetgrass is the only one that has been released theatrically, offering a fascinating look at something that is destined to soon be gone forever. Sweetgrass is screening April 17 at 6:30 in the Focus on the Sensory Ethnography Lab section of the Film Society of Lincoln Center series “Art of the Real,” held in conjunction with the Whitney Biennial, and will be followed by a Q&A with Barbash. The inaugural festival runs April 11-26, featuring more than three dozen works that push the boundaries of documentary film.

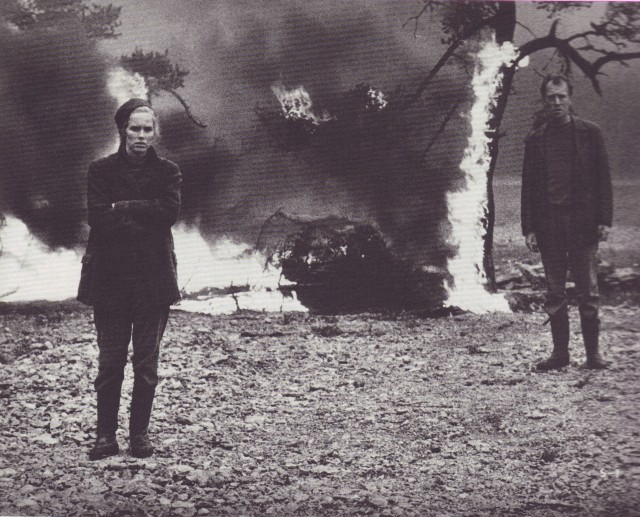

Ingmar Bergman’s Shame is a brilliant examination of the physical and psychological impact of war, as seen through the eyes of a happily married couple who innocently get caught in the middle of the brutality. Jan (Max von Sydow) and Eva Rosenberg (Liv Ullmann) have isolated themselves from society, living without a television and with a broken radio, maintaining a modest farm on a relatively desolate island a ferry ride from the mainland. As the film opens, they are shown to be a somewhat ordinary husband and wife, brushing their teeth, making coffee, and discussing having a child. But soon they are thrust into a horrific battle between two unnamed sides, fighting for reasons that are never given. As Jan and Eva struggle to survive, they are forced to make decisions that threaten to destroy everything they have built together. Shot in stark black-and-white by master cinematographer Sven Nykvist, Shame is a powerful, emotional antiwar statement that makes its point through intense visual scenes rather than narrative rhetoric. Jan and Eva huddle in corners or nearly get lost in crowds, then are seen traversing a smoky, postapocalyptic landscape riddled with dead bodies. Made during the Vietnam War, Shame is Bergman’s most violent, action-filled film; bullets can be heard over the opening credits, announcing from the very beginning that this is going to be something different from a director best known for searing personal dramas. However, at its core, Shame is just that, a gripping, intense tale of a man and a woman who try to preserve their love in impossible times. Ullmann and von Sydow both give superb, complex performances, creating believable characters who will break your heart. Shame is screening December 14 and 18 at the Elinor Bunin Munroe Film Center as part of the Film Society of Lincoln Center series “Liv & Ingmar: The Films,” being held in conjunction with the theatrical release of Dheeraj Akolkar’s poetic new documentary, Liv & Ingmar; the festival continues with such other Ullmann/Bergman pairings as Scenes from a Marriage, Saraband, The Passion of Anna, and Persona.

Ingmar Bergman’s Shame is a brilliant examination of the physical and psychological impact of war, as seen through the eyes of a happily married couple who innocently get caught in the middle of the brutality. Jan (Max von Sydow) and Eva Rosenberg (Liv Ullmann) have isolated themselves from society, living without a television and with a broken radio, maintaining a modest farm on a relatively desolate island a ferry ride from the mainland. As the film opens, they are shown to be a somewhat ordinary husband and wife, brushing their teeth, making coffee, and discussing having a child. But soon they are thrust into a horrific battle between two unnamed sides, fighting for reasons that are never given. As Jan and Eva struggle to survive, they are forced to make decisions that threaten to destroy everything they have built together. Shot in stark black-and-white by master cinematographer Sven Nykvist, Shame is a powerful, emotional antiwar statement that makes its point through intense visual scenes rather than narrative rhetoric. Jan and Eva huddle in corners or nearly get lost in crowds, then are seen traversing a smoky, postapocalyptic landscape riddled with dead bodies. Made during the Vietnam War, Shame is Bergman’s most violent, action-filled film; bullets can be heard over the opening credits, announcing from the very beginning that this is going to be something different from a director best known for searing personal dramas. However, at its core, Shame is just that, a gripping, intense tale of a man and a woman who try to preserve their love in impossible times. Ullmann and von Sydow both give superb, complex performances, creating believable characters who will break your heart. Shame is screening December 14 and 18 at the Elinor Bunin Munroe Film Center as part of the Film Society of Lincoln Center series “Liv & Ingmar: The Films,” being held in conjunction with the theatrical release of Dheeraj Akolkar’s poetic new documentary, Liv & Ingmar; the festival continues with such other Ullmann/Bergman pairings as Scenes from a Marriage, Saraband, The Passion of Anna, and Persona.