LE AMICHE (Michelangelo Antonioni, 1955)

Film Society of Lincoln Center, Walter Reade Theater, Francesca Beale Theater

144/165 West 65th St. between Eighth Ave. & Broadway

Friday, May 29, 4:15, and Sunday, May 31, 9:00

Festival runs May 22-31

212-875-5050

www.filmlinc.com

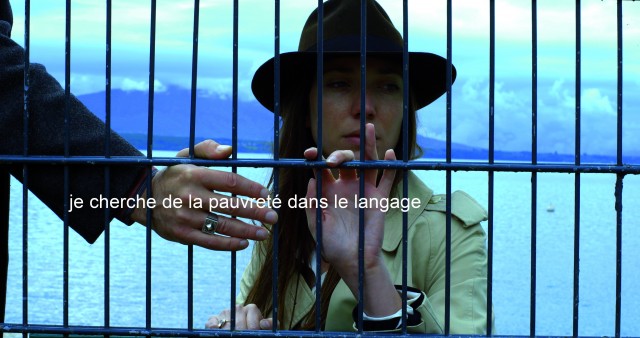

Winner of the Silver Lion at the 1955 Venice Film Festival, Michelangelo Antonioni’s sublimely marvelous Le Amiche follows the life and loves of a group of oh-so-fabulous catty, chatty, and ultra-fashionable Italian women and the men they keep around for adornment. Returning to her native Turin after having lived in Rome for many years, Clelia (Eleonora Rossi Drago) discovers that the young woman in the hotel room next to hers, Rosetta (Madeleine Fischer), has attempted suicide, thrusting Clelia into the middle of a collection of self-centered girlfriends who make the shenanigans of George Cukor’s The Women look like child’s play. The leader of the vain, vapid vamps is Momina (Yvonne Furneaux), who carefully orchestrates situations to her liking, particularly when it comes to her husband and her various, ever-changing companions, primarily architect Cesare (Franco Fabrizi). As Rosetta falls for painter Lorenzo (Gabriele Ferzetti), who is married to ceramicist Nene (Valentina Cortese), Clelia considers a relationship with Cesare’s assistant, Carlo (Ettore Manni), and the flighty Mariella (Anna Maria Pancani) considers just about anyone. Based on the novella Tra Donne Sole (“Among Only Women”) by Cesare Pavese, Le Amiche is one of Antonioni’s best, and least well known, films, an intoxicating and thoroughly entertaining precursor to his early 1960s trilogy, L’Avventura, La Notte, and L’Eclisse. Skewering the not-very-discreet “charm” of the Italian bourgeoisie, Antonioni mixes razor-sharp dialogue with scenes of wonderful ennui, all shot in glorious black and white by Gianni Di Venanzo.

Winner of the Silver Lion at the 1955 Venice Film Festival, Michelangelo Antonioni’s sublimely marvelous Le Amiche follows the life and loves of a group of oh-so-fabulous catty, chatty, and ultra-fashionable Italian women and the men they keep around for adornment. Returning to her native Turin after having lived in Rome for many years, Clelia (Eleonora Rossi Drago) discovers that the young woman in the hotel room next to hers, Rosetta (Madeleine Fischer), has attempted suicide, thrusting Clelia into the middle of a collection of self-centered girlfriends who make the shenanigans of George Cukor’s The Women look like child’s play. The leader of the vain, vapid vamps is Momina (Yvonne Furneaux), who carefully orchestrates situations to her liking, particularly when it comes to her husband and her various, ever-changing companions, primarily architect Cesare (Franco Fabrizi). As Rosetta falls for painter Lorenzo (Gabriele Ferzetti), who is married to ceramicist Nene (Valentina Cortese), Clelia considers a relationship with Cesare’s assistant, Carlo (Ettore Manni), and the flighty Mariella (Anna Maria Pancani) considers just about anyone. Based on the novella Tra Donne Sole (“Among Only Women”) by Cesare Pavese, Le Amiche is one of Antonioni’s best, and least well known, films, an intoxicating and thoroughly entertaining precursor to his early 1960s trilogy, L’Avventura, La Notte, and L’Eclisse. Skewering the not-very-discreet “charm” of the Italian bourgeoisie, Antonioni mixes razor-sharp dialogue with scenes of wonderful ennui, all shot in glorious black and white by Gianni Di Venanzo.

Recently restored in 35mm, Le Amiche is a newly rediscovered treasure from one of cinema’s most iconoclastic auteurs. It is screening on May 29 at 4:15 and May 31 at 9:00 in the Film Society of Lincoln Center series “Titanus: A Family Chronicle of Italian Cinema,” a ten-day, twenty-three-film retrospective honoring the Italian production company founded by Gustavo Lombardo in 1904 and later run by his son, Goffredo, and grandson, Guido, that remained active until 1964 (although it continues to occasionally release work). The festival displays the wide range of Titanus’s output, including Dario Argento’s The Bird with Crystal Plumage, Camillo Mastrocinque’s Little Girls and High Finance, Raffaello Matarazzo’s The White Angel, Elio Petri’s Numbered Days, Federico Fellini’s The Swindle, Giorgio Bianchi’s Cronaca Nera, and Dino Risi’s The Sign of Venus, but not Luchino Visconti’s The Leopard; the tremendous cost of filming Giuseppe di Lampedusa’s epochal novel played a major role in the company’s downward fortune.

Last year, award-winning Argentine writer-director Martín Rejtman returned with his first film in eight years (and only his fourth feature in his nearly thirty-year career), the absurdist black comedy Two Shots Fired. The calmly paced story begins as sixteen-year-old Mariano (Rafael Federman), after a night of dancing, goes about his daily chores, swimming laps in his family’s backyard pool (as the dog runs alongside him) and mowing the lawn. He shows no emotion when he accidentally runs over the mower’s electric cord; instead he simply goes into the house for tools to fix it. There he also finds a box with a gun, so he goes into his room, puts the gun against his head, and pulls the trigger, like it’s a perfectly normal thing to do. He then places the barrel against his stomach and shoots himself a second time. The first shot merely grazes his temple, while the second shot seems to have left a bullet lodged in his body. Mariano evenhandedly claims that he is not depressed and was not trying to kill himself, and his friends and family essentially act as if nothing has happened, going on with their simple, ordinary lives. The only ones who appear to be even the slightest bit concerned are his mother (Susana Pampin), who secretly hides all the scissors and kitchen knives, and the dog, who runs away.

Last year, award-winning Argentine writer-director Martín Rejtman returned with his first film in eight years (and only his fourth feature in his nearly thirty-year career), the absurdist black comedy Two Shots Fired. The calmly paced story begins as sixteen-year-old Mariano (Rafael Federman), after a night of dancing, goes about his daily chores, swimming laps in his family’s backyard pool (as the dog runs alongside him) and mowing the lawn. He shows no emotion when he accidentally runs over the mower’s electric cord; instead he simply goes into the house for tools to fix it. There he also finds a box with a gun, so he goes into his room, puts the gun against his head, and pulls the trigger, like it’s a perfectly normal thing to do. He then places the barrel against his stomach and shoots himself a second time. The first shot merely grazes his temple, while the second shot seems to have left a bullet lodged in his body. Mariano evenhandedly claims that he is not depressed and was not trying to kill himself, and his friends and family essentially act as if nothing has happened, going on with their simple, ordinary lives. The only ones who appear to be even the slightest bit concerned are his mother (Susana Pampin), who secretly hides all the scissors and kitchen knives, and the dog, who runs away.

Named Best First Film at the 2014 Jerusalem Film Festival, Bazi Gete’s Red Leaves is a compelling cinema-vérité-style tale of an Ethiopian Jewish family dealing with a very stubborn patriarch following the death of his wife. The film opens as a man tries to lead a goat to slaughter, an apt metaphor for what might become of seventy-four-year-old Meseganio Tadela (Debebe Eshetu), a solemn survivor of Sudan who suddenly tells his family that he has sold his home and will spend the rest of his life living with each of them in Tel Aviv. So he shows up unannounced at one son’s home, then another’s, leaving behind psychological wreckage that might never be undone. A stubborn man of few words, Meseganio is determined to preserve the old traditions in changing times that are quickly passing him by. His adherence gets him into trouble with his children and grandchildren, who have different priorities. Gete and cinematographer Edan Sasson use a handheld camera that puts the viewer at the Shabbat dinner table with the family as they playfully joke around with one another but afterward reveals Meseganio sitting by himself as everyone else goes on about their life without him. He can’t keep from interfering in his children’s lives, and he sticks his nose in various situations that turn volatile, from a confrontation with his granddaughter Bosna (Ruti Asarsai) to battles with his son Baruch’s (Meir Dassa) wife, Zehava (Hanna Haiela), and his other son, Moshe (Solomon Mersha). “Nothing to live for,” Meseganio’s friend Achenaf (Molla Megistu) says, but Meseganio has plenty to live for, if he would only recognize it. The final twenty minutes, and the wholly ambiguous ending, are heartbreaking and painful as the old man tries to find his way.

Named Best First Film at the 2014 Jerusalem Film Festival, Bazi Gete’s Red Leaves is a compelling cinema-vérité-style tale of an Ethiopian Jewish family dealing with a very stubborn patriarch following the death of his wife. The film opens as a man tries to lead a goat to slaughter, an apt metaphor for what might become of seventy-four-year-old Meseganio Tadela (Debebe Eshetu), a solemn survivor of Sudan who suddenly tells his family that he has sold his home and will spend the rest of his life living with each of them in Tel Aviv. So he shows up unannounced at one son’s home, then another’s, leaving behind psychological wreckage that might never be undone. A stubborn man of few words, Meseganio is determined to preserve the old traditions in changing times that are quickly passing him by. His adherence gets him into trouble with his children and grandchildren, who have different priorities. Gete and cinematographer Edan Sasson use a handheld camera that puts the viewer at the Shabbat dinner table with the family as they playfully joke around with one another but afterward reveals Meseganio sitting by himself as everyone else goes on about their life without him. He can’t keep from interfering in his children’s lives, and he sticks his nose in various situations that turn volatile, from a confrontation with his granddaughter Bosna (Ruti Asarsai) to battles with his son Baruch’s (Meir Dassa) wife, Zehava (Hanna Haiela), and his other son, Moshe (Solomon Mersha). “Nothing to live for,” Meseganio’s friend Achenaf (Molla Megistu) says, but Meseganio has plenty to live for, if he would only recognize it. The final twenty minutes, and the wholly ambiguous ending, are heartbreaking and painful as the old man tries to find his way.