AFTERNOON OF A FAUN: TANAQUIL LE CLERCQ (Nancy Buirski, 2013)

Film Society of Lincoln Center

Walter Reade Theater, 165 West 65th St. between Broadway & Amsterdam Ave.

Monday, September 30, 6:00 pm

Howard Gilman Theater, 144 West 65th St. between Broadway & Amsterdam Ave.

Friday, October 11, 1:00

Francesca Beale Theater, 144 West 65th St. between Broadway & Amsterdam Ave.

Sunday, October 13, 6:00

Festival runs September 27 – October 13

212-875-5601

www.filmlinc.com

“Tanny’s body created inspiration for choreographers,” one of the interviewees says in Nancy Buirski’s documentary Afternoon of a Faun: Tanaquil Le Clercq. “They could do things that they hadn’t seen before.” The American Masters presentation examines the life and career of prima ballerina Tanaquil Le Clercq, affectionately known as Tanny, who took the dance world by storm in the 1940s and ’50s before tragically being struck down by polio in 1956 at the age of twenty-seven. Le Clercq served as muse to both Jerome Robbins, who made Afternoon of a Faun for her, and George Balanchine, who created such seminal works as Western Symphony, La Valse, and Symphony in C for Le Clercq — and married Tanny in 1952. In the documentary, Buirski (The Loving Story) speaks with Arthur Mitchell and Jacques D’Amboise, who both danced with Le Clercq, her childhood friend Pat McBride Lousada, and Barbara Horgan, Balanchine’s longtime assistant, while also including an old interview with Robbins, who deeply loved Le Clercq as well. The film features spectacular, rarely seen archival footage of Le Clercq performing many of the New York City Ballet’s classic works, both onstage and even on The Red Skelton Show. The name Tanaquil relates to the word “omen” — in history, Tanaquil, the wife of the fifth king of Rome, was somewhat of a prophetess who believed in omens — and the film details several shocking omens surrounding her contracting polio. The film would benefit from sharing more information about Le Clercq’s life post-1957 — she died on New Year’s Eve in 2000 at the age of seventy-one — but Afternoon of a Faun is still a lovely, compassionate, and heartbreaking look at a one-of-a-kind performer. Afternoon of a Faun is screening at the New York Film Festival on September 30 at the Walter Reade Theater (followed by a Q&A with the director), on October 11 at the Howard Gilman Theater, and on October 13 at the Francesca Beale Theater.

“Tanny’s body created inspiration for choreographers,” one of the interviewees says in Nancy Buirski’s documentary Afternoon of a Faun: Tanaquil Le Clercq. “They could do things that they hadn’t seen before.” The American Masters presentation examines the life and career of prima ballerina Tanaquil Le Clercq, affectionately known as Tanny, who took the dance world by storm in the 1940s and ’50s before tragically being struck down by polio in 1956 at the age of twenty-seven. Le Clercq served as muse to both Jerome Robbins, who made Afternoon of a Faun for her, and George Balanchine, who created such seminal works as Western Symphony, La Valse, and Symphony in C for Le Clercq — and married Tanny in 1952. In the documentary, Buirski (The Loving Story) speaks with Arthur Mitchell and Jacques D’Amboise, who both danced with Le Clercq, her childhood friend Pat McBride Lousada, and Barbara Horgan, Balanchine’s longtime assistant, while also including an old interview with Robbins, who deeply loved Le Clercq as well. The film features spectacular, rarely seen archival footage of Le Clercq performing many of the New York City Ballet’s classic works, both onstage and even on The Red Skelton Show. The name Tanaquil relates to the word “omen” — in history, Tanaquil, the wife of the fifth king of Rome, was somewhat of a prophetess who believed in omens — and the film details several shocking omens surrounding her contracting polio. The film would benefit from sharing more information about Le Clercq’s life post-1957 — she died on New Year’s Eve in 2000 at the age of seventy-one — but Afternoon of a Faun is still a lovely, compassionate, and heartbreaking look at a one-of-a-kind performer. Afternoon of a Faun is screening at the New York Film Festival on September 30 at the Walter Reade Theater (followed by a Q&A with the director), on October 11 at the Howard Gilman Theater, and on October 13 at the Francesca Beale Theater.

During his sixteen-year career, Sixth Generation Chinese filmmaker Jia Zhangke has made both narrative works (The World, Platform, Still Life) and documentaries (Useless, I Wish I Knew), with his fiction films containing elements of nonfiction and vice versa. Such is the case with his latest film, the powerful A Touch of Sin, which explores four based-on-fact outbreaks of shocking violence in four different regions of China. In Shanxi, outspoken miner Dahai (Jiang Wu) won’t stay quiet about the rampant corruption of the village elders. In Chongqing, married migrant worker and father Zhao San (Wang Baoqiang) obtains a handgun and is not afraid to use it. In Hubei, brothel receptionist Ziao Yu (Zhao Tao, Jia’s longtime muse and now wife) can no longer take the abuse and assumptions of the male clientele. And in Dongguan, young Xiao Hui (Luo Lanshan) tries to make a life for himself but is soon overwhelmed by his lack of success. Inspired by King Hu’s 1971 wuxia film A Touch of Zen, Jia also owes a debt to Max Ophüls’s 1950 bittersweet romance La Ronde, in which a character from one segment continues into the next, linking the stories. In A Touch of Sin, there is also a character connection in each successive tale, though not as overt, as Jia makes a wry, understated comment on the changing ways that people connect in modern society. In depicting these four acts of violence, Jia also exposes the widening economic gap between the rich and the poor and the social injustice that is prevalent all over contemporary China — as well as the rest of the world — leading to dissatisfied individuals fighting for their dignity in extreme ways. A gripping, frightening film that earned Jia the Best Screenplay Award at Cannes this year, A Touch of Sin is an official selection of the fifty-first New York Film Festival, screening September 28 at Alice Tully Hull and October 2 at the Francesca Beale Theater, with Jia and Zhao participating in a Q&A following the first show. (The film then opens October 4 at Lincoln Plaza and the IFC Center.)

During his sixteen-year career, Sixth Generation Chinese filmmaker Jia Zhangke has made both narrative works (The World, Platform, Still Life) and documentaries (Useless, I Wish I Knew), with his fiction films containing elements of nonfiction and vice versa. Such is the case with his latest film, the powerful A Touch of Sin, which explores four based-on-fact outbreaks of shocking violence in four different regions of China. In Shanxi, outspoken miner Dahai (Jiang Wu) won’t stay quiet about the rampant corruption of the village elders. In Chongqing, married migrant worker and father Zhao San (Wang Baoqiang) obtains a handgun and is not afraid to use it. In Hubei, brothel receptionist Ziao Yu (Zhao Tao, Jia’s longtime muse and now wife) can no longer take the abuse and assumptions of the male clientele. And in Dongguan, young Xiao Hui (Luo Lanshan) tries to make a life for himself but is soon overwhelmed by his lack of success. Inspired by King Hu’s 1971 wuxia film A Touch of Zen, Jia also owes a debt to Max Ophüls’s 1950 bittersweet romance La Ronde, in which a character from one segment continues into the next, linking the stories. In A Touch of Sin, there is also a character connection in each successive tale, though not as overt, as Jia makes a wry, understated comment on the changing ways that people connect in modern society. In depicting these four acts of violence, Jia also exposes the widening economic gap between the rich and the poor and the social injustice that is prevalent all over contemporary China — as well as the rest of the world — leading to dissatisfied individuals fighting for their dignity in extreme ways. A gripping, frightening film that earned Jia the Best Screenplay Award at Cannes this year, A Touch of Sin is an official selection of the fifty-first New York Film Festival, screening September 28 at Alice Tully Hull and October 2 at the Francesca Beale Theater, with Jia and Zhao participating in a Q&A following the first show. (The film then opens October 4 at Lincoln Plaza and the IFC Center.)

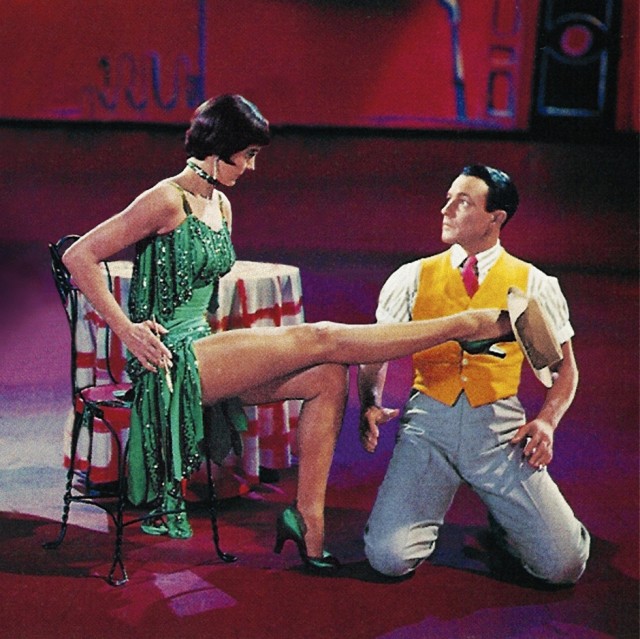

The 1952 MGM musical Singin’ in the Rain is one of the all-time-great movies about movies, in this case focusing on the treacherous transition from silent films to talkies. It’s the mid-1920s, and the darlings of the silver screen are handsome Don Lockwood (Gene Kelly) and blonde bombshell Lina Lamont (Jean Hagen). They’re supposedly just as hot offscreen as on, as Don explains to radio gossip host Dora Bailey (Madge Blake, later best known as Aunt Harriet on the Batman TV series) at their latest Hollywood premiere, but in actuality the debonair Don can’t stand the none-too-bright yet still conniving Lina. After accidentally bumping into Kathy Selden (Debbie Reynolds), an independent-thinking young woman who claims to not even like the movies, Don is soon trying to chase her down, determined to get to know her better. Meanwhile, studio head R. F. Simpson (Millard Mitchell) decides he has to capitalize on the surprise success of the first talking picture, The Jazz Singer, by turning the latest Lockwood-Lamont movie, The Dueling Cavalier, into a talkie, with initially disastrous results, threatening to bring everything and everyone crashing down.

The 1952 MGM musical Singin’ in the Rain is one of the all-time-great movies about movies, in this case focusing on the treacherous transition from silent films to talkies. It’s the mid-1920s, and the darlings of the silver screen are handsome Don Lockwood (Gene Kelly) and blonde bombshell Lina Lamont (Jean Hagen). They’re supposedly just as hot offscreen as on, as Don explains to radio gossip host Dora Bailey (Madge Blake, later best known as Aunt Harriet on the Batman TV series) at their latest Hollywood premiere, but in actuality the debonair Don can’t stand the none-too-bright yet still conniving Lina. After accidentally bumping into Kathy Selden (Debbie Reynolds), an independent-thinking young woman who claims to not even like the movies, Don is soon trying to chase her down, determined to get to know her better. Meanwhile, studio head R. F. Simpson (Millard Mitchell) decides he has to capitalize on the surprise success of the first talking picture, The Jazz Singer, by turning the latest Lockwood-Lamont movie, The Dueling Cavalier, into a talkie, with initially disastrous results, threatening to bring everything and everyone crashing down.