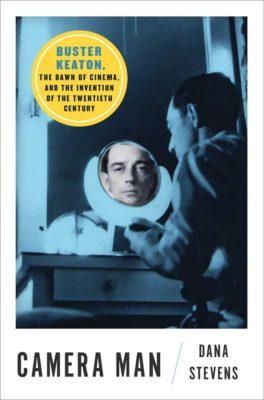

Aliocha (Aurelia Arandi-Longpre) and Jeff (Noah Parker) get close in Who by Fire

WHO BY FIRE (COMME LE FEU) (Philippe Lesage, 2024)

Film at Lincoln Center

Elinor Bunin Munroe Film Center, Francesca Beale Theater

144 West Sixty-Fifth St. between Broadway & Amsterdam Ave.

March 14-20

www.filmlinc.org

www.kimstim.com

Winner of the Grand Prix from the Generation 14plus International Jury at the 2024 Berlinale, Quebecois writer-director Philippe Lesage’s Who by Fire (Comme le feu) is two and a half hours of angst, anger, and jealousy, a coming-of-age drama with a harrowing final fifteen minutes.

One of the special prayers recited during the Jewish High Holidays is the poetic psalm Unetaneh Tokef, which describes repentance, prayer, and charity and includes the following lines: “How many shall pass away and how many shall be born, / Who shall live and who shall die, / Who shall reach the end of his days and who shall not, / Who shall perish by water and who by fire, / Who by sword and who by wild beast, / Who by famine and who by thirst, / Who by earthquake and who by plague, / Who by strangulation and who by stoning, / Who shall have rest and who shall wander, / Who shall be at peace and who shall be pursued, / Who shall be at rest and who shall be tormented, / Who shall be exalted and who shall be brought low, / Who shall become rich and who shall be impoverished.” That quote, which was adapted by Canadian singer-songwriter Leonard Cohen into the 1974 song “Who by Fire,” captures the essence of the film, which opens March 14 at Lincoln Center, with Lesage participating in Q&As at the 6:15 screening March 14 and the 3:15 show on March 15.

The story unfolds at a secluded cabin in the gorgeous Canadian woods of Haute-Mauricie, where film director Blake Cadieux (Arieh Worthalter) has invited his former longtime collaborator, screenwriter Albert Gary (Paul Ahmarani), to spend some time. Joining Albert are his college-age daughter, Aliocha (Aurelia Arandi-Longpre), his seventeen-year-old son, Max (Antoine Marchand-Gagnon), and Max’s best friend, the shy, uneasy Jeff (Noah Parker). After a successful series of fiction films, Blake and Albert had a falling out, as the former turned to documentaries and the latter to animated television.

Blake lives with his editor, Millie (Sophie Desmarais), housekeeper, Barney (Carlo Harrietha), cook, Ferran (Guillaume Laurin), and dog, Ingmar (Kamo). Also arriving are well-known actress Hélène Falke (Irène Jacob) and her partner, Eddy (Laurent Lucas).

Over the course of several days, there is a lot of cigarette smoking and wine drinking, discussions about art and responsibility, sexual flirtations, and angry arguments between Blake and Albert that go beyond nasty, in addition to hunting, fishing, and white water rafting in the great outdoors, not all of which goes well.

Three uncut dinner scenes anchor Philippe Lesage’s Who by Fire

Who by Fire is anchored by three uncut ten-minute dinner scenes in which tensions flare, primarily involving Blake and Albert, including one in which oenophile Albert accuses Blake of switching out one of his wines. In two of the scenes, cinematographer Balthazar Lab’s camera remains motionless on one end of the long table, while in the third the camera eventually moves around to focus on Albert having an episode.

But at the center of the story is Jeff, who is awkward in his thoughts and actions. The film opens with Albert, his children, and Jeff driving on a deserted highway to be met by Blake’s helicopter. The first shot inside the car is of two young people with their hands on their knees; we don’t see their faces but can feel that at least one of them wants to touch the other. We soon learn that it is Aliocha — whose name in Russian translates to “defender of men” — and Jeff (the one who wants their hands and legs to meet). Later, after Max tells Jeff that he once caught his sister looking at S&M porn, Jeff makes a misguided play for her and, shunned, runs into the woods with his tail between his legs and becomes lost. After he is rescued, he grows mad at Blake when he catches the director and Aliocha in an intimate moment.

Most of the characters are either unlikable or not fully defined, so spending more than two and a half hours with them is a lot to ask. The cast does its job admirably, finding their way around some of Lesage’s occasionally meandering script. Cédric Dind-Lavoie’s droning score ranges from lilting to elegiac. A party scene that ends with the characters singing and dancing to the B-52’s song “Rock Lobster” starts out fun but quickly becomes something else, no mere break from the glum atmosphere.

Lesage (Les démons, Genèse) expertly balances the claustrophobic interior scenes by glorying in the beauty of nature, with outdoor scenes that celebrate the world outside. But not everyone is as comfortable as he is in those surroundings, leading to one tragedy that is followed by an even worse one, at least as far as manipulating an audience goes.

Who by Fire raises many of the questions asked in the Unetaneh Tokef, and he answers some of them while leaving plenty open to interpretation, as does Cohen when he asks, “And who shall I say is calling?”

[Mark Rifkin is a Brooklyn-born, Manhattan-based writer and editor; you can follow him on Substack here.]