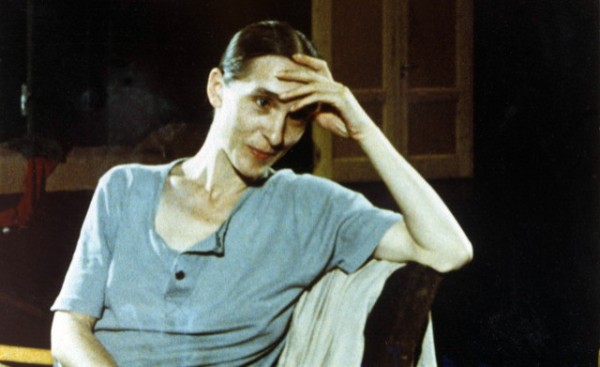

Yuichi Sumida (Shota Sometani) and Keiko Chazawa (Fumi Nikaido) face similar situations in different ways in Sion Sono’s HIMIZU

HIMIZU (Sion Sono, 2011)

Film Society of Lincoln Center, Elinor Bunin Munroe Film Center

144 West 65th St. between Broadway & Amsterdam Ave.

March 14-20

212-875-5601

www.filmlinc.com

www.sonosion.com

“I know all things. I know pink cheeks from wan. I know death, who devours all. I know everything. Everything but myself,” Keiko Chazawa (Fumi Nikaido) says at the beginning of Himizu over a sweeping shot of the destruction wrought by the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami and Fukushima nuclear meltdown. Keiko is a strange, deeply troubled teen stalking another strange, deeply troubled teen, Yuichi Sumida (Shota Sometani), following him around school, covering her bedroom walls with things he has said, and hanging out at his family’s extremely low rent boat basin. Yuichi’s mother (Makiko Watanabe) tramps herself out while his father (Ken Mitsuishi), who owes money to yakuza boss Kaneko (Denden), regularly shows up drunk and tells Yuichi that he blames his terrible life on his son, that he wishes Yuichi were never born. Meanwhile, Keiko’s mother (Asuka Kurosawa) is building a gallows in her house, hoping that her daughter will use it to kill herself. Somehow, amid all this craziness and pain — and extreme violence — writer-director Sion Sono (Bad Film, Suicide Club) manages to tell a poignant tale of adolescence as the older generation in Japan is leaving a discouraging future for the younger generation, which is fraught with hopelessness and fear of what will be left for them. The horribly abused Yuichi walks through life like a zombie, not fighting back as he is beaten up by his father and the yakuza. He is surrounded by an unusual group of adults who he allows to live on his property in tents, as they have lost everything in the economic crisis. They’re a wacky bunch, led by the somewhat sage Yoruno (Tetsu Watanabe), that serves as a kind of surrogate family for both Yuichi and Keiko, wanting only the best for them despite Yuichi’s coldness and unwillingness to accept any kind of help. But Yuichi soon simmers until he ultimately explodes, and when he does, everyone had better watch out.

“I know all things. I know pink cheeks from wan. I know death, who devours all. I know everything. Everything but myself,” Keiko Chazawa (Fumi Nikaido) says at the beginning of Himizu over a sweeping shot of the destruction wrought by the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami and Fukushima nuclear meltdown. Keiko is a strange, deeply troubled teen stalking another strange, deeply troubled teen, Yuichi Sumida (Shota Sometani), following him around school, covering her bedroom walls with things he has said, and hanging out at his family’s extremely low rent boat basin. Yuichi’s mother (Makiko Watanabe) tramps herself out while his father (Ken Mitsuishi), who owes money to yakuza boss Kaneko (Denden), regularly shows up drunk and tells Yuichi that he blames his terrible life on his son, that he wishes Yuichi were never born. Meanwhile, Keiko’s mother (Asuka Kurosawa) is building a gallows in her house, hoping that her daughter will use it to kill herself. Somehow, amid all this craziness and pain — and extreme violence — writer-director Sion Sono (Bad Film, Suicide Club) manages to tell a poignant tale of adolescence as the older generation in Japan is leaving a discouraging future for the younger generation, which is fraught with hopelessness and fear of what will be left for them. The horribly abused Yuichi walks through life like a zombie, not fighting back as he is beaten up by his father and the yakuza. He is surrounded by an unusual group of adults who he allows to live on his property in tents, as they have lost everything in the economic crisis. They’re a wacky bunch, led by the somewhat sage Yoruno (Tetsu Watanabe), that serves as a kind of surrogate family for both Yuichi and Keiko, wanting only the best for them despite Yuichi’s coldness and unwillingness to accept any kind of help. But Yuichi soon simmers until he ultimately explodes, and when he does, everyone had better watch out.

Himizu, the title of which refers to a species of Japanese mole, is based on Minoru Furuya’s manga, with Sono making major changes to the script after the earthquake, incorporating yet more disaster into the lives of Yuichi and Keiko. Sometani (Parasyte) and Nikaido (Sono’s Why Don’t You Play in Hell?) excel as the teens, her character’s obsessiveness working well against his laissez-faire attitude; the two were named Best New Actors at the Venice Film Festival for their performances. The supporting cast, which also includes Mitsuru Fukikoshi, Megumi Kagurazaka, Yosuke Kubozuka, Taro Suwa, and Setchin Kawaya, contributes to the film’s cultlike charm, although it is too long, with several false endings, and Tomohide Harada’s score tends to be overly sentimental. But those drawbacks are more than offset by Sôhei Tanikawa’s beautiful cinematography, which is filled with lasting images, perhaps none so memorable as the tilted shack that sticks out from the middle of the lake, a constant reminder of what was — and perhaps what will be. Himizu is having a special engagement March 14-20 at the Film Society of Lincoln Center, accompanied by Sono’s Guilty of Romance, the conclusion of his Hate trilogy, which began with Love Exposure and continued with Cold Fish.

Award-winning Haitian filmmaker Raoul Peck’s Fatal Assistance begins by posting remarkable numbers onscreen: In the wake of the devastating earthquake that hit his native country on January 12, 2010, there were 230,000 deaths, 300,000 wounded, and 1.5 million people homeless, with some 4,000 NGOs coming to Haiti to make use of a promised $11 billion in relief over a five-year period. But as Peck reveals, there is significant controversy over where the money is and how it’s being spent as the troubled Haitian people are still seeking proper health care and a place to live. “The line between intrusion, support, and aid is very fine,” says Jean-Max Bellerive, the Haitian prime minister at the time of the disaster, explaining that too many of the donors want to cherry-pick how their money is used. Bill Vastine, senior “debris” adviser for the Interim Commission for the Reconstruction of Haiti (CIRH), which was co-chaired by Bellerive and President Bill Clinton, responds, “The international community said they were gonna grant so many billions of dollars to Haiti. That didn’t mean we were gonna send so many billions of dollars to a bank account and let the Haitian government do with it as they will.” Somewhere in the middle is CIRH senior housing adviser Priscilla Phelps, who seems to be the only person who recognizes why the relief effort has turned into a disaster all its own; by the end of the film, she is struggling to hold back tears.

Award-winning Haitian filmmaker Raoul Peck’s Fatal Assistance begins by posting remarkable numbers onscreen: In the wake of the devastating earthquake that hit his native country on January 12, 2010, there were 230,000 deaths, 300,000 wounded, and 1.5 million people homeless, with some 4,000 NGOs coming to Haiti to make use of a promised $11 billion in relief over a five-year period. But as Peck reveals, there is significant controversy over where the money is and how it’s being spent as the troubled Haitian people are still seeking proper health care and a place to live. “The line between intrusion, support, and aid is very fine,” says Jean-Max Bellerive, the Haitian prime minister at the time of the disaster, explaining that too many of the donors want to cherry-pick how their money is used. Bill Vastine, senior “debris” adviser for the Interim Commission for the Reconstruction of Haiti (CIRH), which was co-chaired by Bellerive and President Bill Clinton, responds, “The international community said they were gonna grant so many billions of dollars to Haiti. That didn’t mean we were gonna send so many billions of dollars to a bank account and let the Haitian government do with it as they will.” Somewhere in the middle is CIRH senior housing adviser Priscilla Phelps, who seems to be the only person who recognizes why the relief effort has turned into a disaster all its own; by the end of the film, she is struggling to hold back tears.