Ian Fiscuteanu brings to life the slow death of a unique character in Cristi Puiu’s very dark comedy

THE DEATH OF MR. LAZARESCU (Cristi Puiu, 2005)

IFC Center

323 Sixth Ave. at West Third St.

Wednesday, July 9, 8:45

Series runs July 4-10

212-924-7771

www.ifccenter.com

Poor Mr. Lazarescu. He lives in a shoddy hovel of an apartment in Bucharest, where he drinks too much and gets out too little. He moves around very slowly and has trouble saying what’s on his mind, even to his three cats. His family is sick and tired of telling him to lay off the booze, so they ignore his complaints. Suffering from headaches and stomach pain, he phones for an ambulance several times, but it arrives only after a neighbor calls as well. Mr. Lazarescu then spends the rest of this very long night fading away as he is taken to hospital after hospital by the ambulance nurse, who gets involved in a seemingly endless battle with doctors to try to save him. Ian Fiscuteanu is sensationally realistic as Mr. Lazarescu; you’ll quickly forget that he’s not really a drunk, disgusting, dying old man. Luminita Gheorghiu is excellent as Mioara, the nurse who gets caught up in Mr. Lazarescu’s case. Winner of the Cannes Film Festival’s Un Certain Regard Award, cowriter-director Cristi Puiu’s very dark comedy is simply captivating; despite a slow start, it’ll pull you in with its well-choreographed scenes, documentary style, and careful camera movement. (Also look for the subtle and very specific naming of characters.) Using Éric Rohmer’s “Six Moral Tales” as inspiration, Puiu has said that The Death of Mr. Lazarescu is the first of his own “Six Stories from the Bucharest Suburbs,” this one dealing with “the love of humanity,” followed by 2010’s Aurora.

Poor Mr. Lazarescu. He lives in a shoddy hovel of an apartment in Bucharest, where he drinks too much and gets out too little. He moves around very slowly and has trouble saying what’s on his mind, even to his three cats. His family is sick and tired of telling him to lay off the booze, so they ignore his complaints. Suffering from headaches and stomach pain, he phones for an ambulance several times, but it arrives only after a neighbor calls as well. Mr. Lazarescu then spends the rest of this very long night fading away as he is taken to hospital after hospital by the ambulance nurse, who gets involved in a seemingly endless battle with doctors to try to save him. Ian Fiscuteanu is sensationally realistic as Mr. Lazarescu; you’ll quickly forget that he’s not really a drunk, disgusting, dying old man. Luminita Gheorghiu is excellent as Mioara, the nurse who gets caught up in Mr. Lazarescu’s case. Winner of the Cannes Film Festival’s Un Certain Regard Award, cowriter-director Cristi Puiu’s very dark comedy is simply captivating; despite a slow start, it’ll pull you in with its well-choreographed scenes, documentary style, and careful camera movement. (Also look for the subtle and very specific naming of characters.) Using Éric Rohmer’s “Six Moral Tales” as inspiration, Puiu has said that The Death of Mr. Lazarescu is the first of his own “Six Stories from the Bucharest Suburbs,” this one dealing with “the love of humanity,” followed by 2010’s Aurora.

The Death of Mr. Lazarescu is screening July 9 at 8:45 as part of the IFC Center series “Time Regained: Cinema’s Present Perfect,” consisting of more than two dozen films that deal with time, being held in conjunction with the upcoming release of Richard Linklater’s Boyhood. The festival runs through July 10 and also includes all of François Truffaut’s Antoine Doinel films, Linklater’s Before trilogy with Ethan Hawke and Julie Delpy, Agnès Varda’s real-time Cleo from 5 to 7, Harold Ramis’s Groundhog Day, Gaspar Noé’s controversial, backward-told Irréversible, Robert Wise’s boxing drama The Set-Up, Vincente Minnelli’s romance The Clock, Akira Kurosawa’s multiple-view Rashomon, and Alfred Hitchcock’s seemingly unedited Rope. Interestingly, IFC is not showing Raoul Ruiz’s Time Regained, based on Marcel Proust’s final volume of In Search of Lost Time and the namesake of the series.

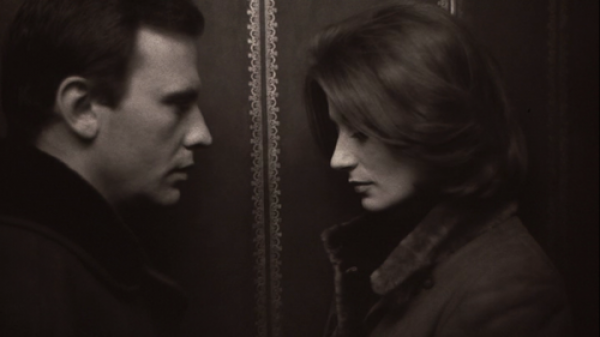

Nominated for the Palme d’Or and a Best Foreign Language Film Oscar, My Night at Maud’s, Éric Rohmer’s fourth entry in his Six Moral Tales series (Claire’s Knee, Love in the Afternoon), continues the French director’s fascinating exploration of love, marriage, and tangled relationships. Three years removed from playing the romantic racecar driver Jean-Louis in Claude Lelouch’s A Man and a Woman, Jean-Louis Trintignant again stars as a man named Jean-Louis, this time a single thirty-four-year-old Michelin engineer living a relatively solitary life in the French suburb of Clermont. A devout Catholic, he is developing an obsession with a fellow churchgoer, the blonde, beautiful Françoise (Marie-Christine Barrault), about whom he knows practically nothing. After bumping into an old school friend, Vidal (Antoine Vitez), the two men delve into deep discussions of religion, Marxism, Pascal, mathematics, Jansenism, and women. Vidal then invites Jean-Louis to the home of his girlfriend, Maud (Françoise Fabian), a divorced single mother with open thoughts about sexuality, responsibility, and morality that intrigue Jean-Louis, for whom respectability and appearance are so important. The conversation turns to such topics as hypocrisy, grace, infidelity, and principles, but Maud eventually tires of such talk. “Dialectic does nothing for me,” she says shortly after explaining that she always sleeps in the nude. Later, when Jean-Louis and Maud are alone, she tells him, “You’re both a shamefaced Christian and a shamefaced Don Juan.” Soon a clearly conflicted Jean-Louis is involved in several love triangles that are far beyond his understanding, so he again seeks solace in church. My Night at Maud’s is a classic French tale, with characters spouting off philosophically while smoking cigarettes, drinking wine and other cocktails, and getting naked. Shot in black-and-white by Néstor Almendros, the film roams from midnight mass to a single woman’s bed and back to church, as Jean-Louis, played with expert concern by Trintignant, is forced to examine his own deep desires and how they relate to his spirituality. Fabian (Belle de Jour, The Letter) is outstanding as Maud, whose freedom titillates and confuses Jean-Louis. One of Rohmer’s best, most accomplished works despite its haughty intellectualism, My Night at Maud’s is screening May 14-16 at 1:30 as part of MoMA’s ongoing series “An Auteurist History of Film,” which continues May 21-23 with Robert Altman’s McCabe and Mrs. Miller and May 28-30 with Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s Merchant of the Four Seasons.

Nominated for the Palme d’Or and a Best Foreign Language Film Oscar, My Night at Maud’s, Éric Rohmer’s fourth entry in his Six Moral Tales series (Claire’s Knee, Love in the Afternoon), continues the French director’s fascinating exploration of love, marriage, and tangled relationships. Three years removed from playing the romantic racecar driver Jean-Louis in Claude Lelouch’s A Man and a Woman, Jean-Louis Trintignant again stars as a man named Jean-Louis, this time a single thirty-four-year-old Michelin engineer living a relatively solitary life in the French suburb of Clermont. A devout Catholic, he is developing an obsession with a fellow churchgoer, the blonde, beautiful Françoise (Marie-Christine Barrault), about whom he knows practically nothing. After bumping into an old school friend, Vidal (Antoine Vitez), the two men delve into deep discussions of religion, Marxism, Pascal, mathematics, Jansenism, and women. Vidal then invites Jean-Louis to the home of his girlfriend, Maud (Françoise Fabian), a divorced single mother with open thoughts about sexuality, responsibility, and morality that intrigue Jean-Louis, for whom respectability and appearance are so important. The conversation turns to such topics as hypocrisy, grace, infidelity, and principles, but Maud eventually tires of such talk. “Dialectic does nothing for me,” she says shortly after explaining that she always sleeps in the nude. Later, when Jean-Louis and Maud are alone, she tells him, “You’re both a shamefaced Christian and a shamefaced Don Juan.” Soon a clearly conflicted Jean-Louis is involved in several love triangles that are far beyond his understanding, so he again seeks solace in church. My Night at Maud’s is a classic French tale, with characters spouting off philosophically while smoking cigarettes, drinking wine and other cocktails, and getting naked. Shot in black-and-white by Néstor Almendros, the film roams from midnight mass to a single woman’s bed and back to church, as Jean-Louis, played with expert concern by Trintignant, is forced to examine his own deep desires and how they relate to his spirituality. Fabian (Belle de Jour, The Letter) is outstanding as Maud, whose freedom titillates and confuses Jean-Louis. One of Rohmer’s best, most accomplished works despite its haughty intellectualism, My Night at Maud’s is screening May 14-16 at 1:30 as part of MoMA’s ongoing series “An Auteurist History of Film,” which continues May 21-23 with Robert Altman’s McCabe and Mrs. Miller and May 28-30 with Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s Merchant of the Four Seasons.

Winner of both the Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film and the Palme d’Or at Cannes, Claude Lelouch’s A Man and a Woman is one of the most popular, and most unusual, romantic love stories ever put on film. Oscar-nominated Anouk Aimée stars as Anne Gauthier and Jean-Louis Trintignant as Jean-Louis Duroc, two people who each has a child in a boarding school in Deauville. Anne, a former actress, and Jean-Louis, a successful racecar driver, seem to hit it off immediately, but they both have pasts that haunt them and threaten any kind of relationship. Shot in three weeks with a handheld camera by Lelouch, who earned nods for Best Director and Best Screenplay (with Pierre Uytterhoeven), A Man and a Woman is a tour-de-force of filmmaking, going from the modern day to the past via a series of flashbacks that at first alternate between color and black-and-white, then shift hues in curious, indeterminate ways. Much of the film takes place in cars, either as Jean-Louis races around a track or the protagonists sit in his red Mustang convertible and talk about their lives, their hopes, their fears. The heat they generate is palpable, making their reluctance to just fall madly, deeply in love that much more heart-wrenching, all set to a memorable soundtrack by Francis Lai. Lelouch, Trintignant, and Aimée revisited the story in 1986 with A Man and a Woman: 20 Years Later, without the same impact and success. A new print of the original will be shown December 16-17 in a grand double feature with Eric Rohmer’s My Night at Maud’s as part of Film Forum’s two-week tribute to Trintignant, leading up to the theatrical release of the French star’s latest, Michael Haneke’s remarkable Palme d’Or winner Amour, which once again displays the actor’s unique range and sensitivity in an unforgettable performance that is likely to finally make him much better known in the United States, at the tender age of eighty-two.

Winner of both the Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film and the Palme d’Or at Cannes, Claude Lelouch’s A Man and a Woman is one of the most popular, and most unusual, romantic love stories ever put on film. Oscar-nominated Anouk Aimée stars as Anne Gauthier and Jean-Louis Trintignant as Jean-Louis Duroc, two people who each has a child in a boarding school in Deauville. Anne, a former actress, and Jean-Louis, a successful racecar driver, seem to hit it off immediately, but they both have pasts that haunt them and threaten any kind of relationship. Shot in three weeks with a handheld camera by Lelouch, who earned nods for Best Director and Best Screenplay (with Pierre Uytterhoeven), A Man and a Woman is a tour-de-force of filmmaking, going from the modern day to the past via a series of flashbacks that at first alternate between color and black-and-white, then shift hues in curious, indeterminate ways. Much of the film takes place in cars, either as Jean-Louis races around a track or the protagonists sit in his red Mustang convertible and talk about their lives, their hopes, their fears. The heat they generate is palpable, making their reluctance to just fall madly, deeply in love that much more heart-wrenching, all set to a memorable soundtrack by Francis Lai. Lelouch, Trintignant, and Aimée revisited the story in 1986 with A Man and a Woman: 20 Years Later, without the same impact and success. A new print of the original will be shown December 16-17 in a grand double feature with Eric Rohmer’s My Night at Maud’s as part of Film Forum’s two-week tribute to Trintignant, leading up to the theatrical release of the French star’s latest, Michael Haneke’s remarkable Palme d’Or winner Amour, which once again displays the actor’s unique range and sensitivity in an unforgettable performance that is likely to finally make him much better known in the United States, at the tender age of eighty-two.