FEAR AND DESIRE (Stanley Kubrick, 1953)

Film Society of Lincoln Center, Walter Reade Theater

165 West 65th St. between Eighth Ave. & Broadway

Tuesday, January 20, 6:15

Festival runs January 14-29 at the Film Society of Lincoln Center and the Jewish Museum

212-875-5050

www.nyjff.org

www.filmlinc.com

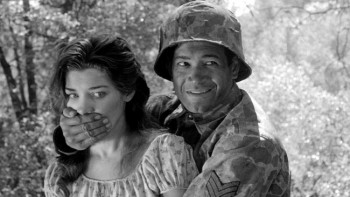

Fear and Desire, Stanley Kubrick’s seldom-seen 1953 psychological war drama and his first full-length film, made when he was just twenty-four, is a curious tale about four soldiers (Steve Coit, Kenneth Harp, Paul Mazursky, and Frank Silvera) trapped six miles behind enemy lines. When they are spotted by a local woman (Virginia Leith), they decide to capture her and tie her up, but leaving Sidney (Mazursky) behind to keep an eye on her turns out to be a bad idea. Meanwhile, they discover a nearby house that has been occupied by the enemy, and they argue over whether to attack or retreat. Written by Howard Sackler, who was a high school classmate of Kubrick’s in the Bronx and would later win the Pulitzer Prize for The Great White Hope, and directed, edited, and photographed by the man who would go on to make such powerful, influential war epics as Paths of Glory, Full Metal Jacket, and Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, Fear and Desire features stilted dialogue, much of which is spoken off-camera and feels like it was dubbed in later. Many of the cuts are jumpy and much of the framing amateurish. Kubrick was ultimately disappointed with the film and wanted it pulled from circulation; instead it was preserved by Eastman House in 1989 and restored twenty years later, which was good news for film lovers, as it is fascinating to watch Kubrick learning as the film continues. His exploration of the psyche of the American soldier is the heart and soul of this compelling black-and-white war drama that is worth seeing for more than just historical reasons.

Fear and Desire, Stanley Kubrick’s seldom-seen 1953 psychological war drama and his first full-length film, made when he was just twenty-four, is a curious tale about four soldiers (Steve Coit, Kenneth Harp, Paul Mazursky, and Frank Silvera) trapped six miles behind enemy lines. When they are spotted by a local woman (Virginia Leith), they decide to capture her and tie her up, but leaving Sidney (Mazursky) behind to keep an eye on her turns out to be a bad idea. Meanwhile, they discover a nearby house that has been occupied by the enemy, and they argue over whether to attack or retreat. Written by Howard Sackler, who was a high school classmate of Kubrick’s in the Bronx and would later win the Pulitzer Prize for The Great White Hope, and directed, edited, and photographed by the man who would go on to make such powerful, influential war epics as Paths of Glory, Full Metal Jacket, and Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, Fear and Desire features stilted dialogue, much of which is spoken off-camera and feels like it was dubbed in later. Many of the cuts are jumpy and much of the framing amateurish. Kubrick was ultimately disappointed with the film and wanted it pulled from circulation; instead it was preserved by Eastman House in 1989 and restored twenty years later, which was good news for film lovers, as it is fascinating to watch Kubrick learning as the film continues. His exploration of the psyche of the American soldier is the heart and soul of this compelling black-and-white war drama that is worth seeing for more than just historical reasons.

“There is a war in this forest. Not a war that has been fought, nor one that will be, but any war,” narrator David Allen explains at the beginning of the film. “And the enemies who struggle here do not exist unless we call them into being. This forest then, and all that happens now, is outside history. Only the unchanging shapes of fear and doubt and death are from our world. These soldiers that you see keep our language and our time but have no other country but the mind.” Fear and Desire lays the groundwork for much of what is to follow in Kubrick’s remarkable career. Fear and Desire is screening with Peter Watkins’s The War Game on January 20 at 6:15 at the Walter Reade Theater as part of the War Against War sidebar program of the twenty-fourth annual New York Jewish Film Festival, which focuses on antiwar films from the 1950s and 1960s; the schedule also includes Gillo Pontecorvo’s Battle of Algiers, Kon Ichikawa’s Fires on the Plain, Konrad Wolf’s I Was Nineteen, and Jean-Luc Godard’s Les Carabiniers, centered by a panel discussion on January 19 at 3:00 at the Elinor Bunin Munroe Film Center (free with advance RSVP) with Kent Jones, Martha Rosler, Harrell Fletcher, and Trevor Paglen, moderated by Jens Hoffmann. Dr. Strangelove is part of the NYJFF as well, showing at the Walter Reade on January 18 at 9:15, introduced by Jennie Livingston.

Kon Ichikawa’s Fires on the Plain is one of the most searing, devastating war movies ever made. Loosely based on Shohei Ooka’s 1952 novel and adapted by Ichikawa’s wife, screenwriter Natto Wada, the controversial film stars Eiji Funakoshi as the sad sack Tamura, a somewhat pathetic tubercular soldier on the island of Leyte in the Philippines at the tail end of World War II. After being released from a military hospital, he returns to his platoon, only to be ordered to go back to the hospital so as not to infect the other men. He is also given a grenade and ordered to blow himself up if the hospital refuses him, which it does. But instead of killing himself, Tamura wanders the vast, empty spaces and dense forests, becoming involved in a series of vignettes that range from darkly comic to utterly horrifying. He encounters a romantic Filipino couple hiding salt under their floorboards, a quartet of soldiers stuffed with yams trying to make it alive to a supposed evacuation zone, and a strange duo selling tobacco and eating “monkey” meat. As Tamura grows weaker and weaker, he considers surrendering to U.S. troops, but even that is not a guarantee of safety, as the farther he travels, the more dead bodies he sees. Fires on the Plain is a blistering attack on the nature of war and what it does to men, but amid all the bleakness and violence, tiny bits of humanity try desperately to seep through against all the odds. And the odds are not very good. Fires on the Plain is screening January 19 at 1:00 at the Walter Reade Theater as part of the War Against War sidebar program of the twenty-fourth annual New York Jewish Film Festival, which focuses on antiwar films from the 1950s and 1960s; the schedule also includes Gillo Pontecorvo’s Battle of Algiers, Stanley Kubrick’s Fear and Desire, Konrad Wolf’s I Was Nineteen, Jean-Luc Godard’s Les Carabiniers, and Peter Watkin’s The War Game, anchored by a panel discussion on January 19 at 3:00 at the Elinor Bunin Munroe Film Center (free with

Kon Ichikawa’s Fires on the Plain is one of the most searing, devastating war movies ever made. Loosely based on Shohei Ooka’s 1952 novel and adapted by Ichikawa’s wife, screenwriter Natto Wada, the controversial film stars Eiji Funakoshi as the sad sack Tamura, a somewhat pathetic tubercular soldier on the island of Leyte in the Philippines at the tail end of World War II. After being released from a military hospital, he returns to his platoon, only to be ordered to go back to the hospital so as not to infect the other men. He is also given a grenade and ordered to blow himself up if the hospital refuses him, which it does. But instead of killing himself, Tamura wanders the vast, empty spaces and dense forests, becoming involved in a series of vignettes that range from darkly comic to utterly horrifying. He encounters a romantic Filipino couple hiding salt under their floorboards, a quartet of soldiers stuffed with yams trying to make it alive to a supposed evacuation zone, and a strange duo selling tobacco and eating “monkey” meat. As Tamura grows weaker and weaker, he considers surrendering to U.S. troops, but even that is not a guarantee of safety, as the farther he travels, the more dead bodies he sees. Fires on the Plain is a blistering attack on the nature of war and what it does to men, but amid all the bleakness and violence, tiny bits of humanity try desperately to seep through against all the odds. And the odds are not very good. Fires on the Plain is screening January 19 at 1:00 at the Walter Reade Theater as part of the War Against War sidebar program of the twenty-fourth annual New York Jewish Film Festival, which focuses on antiwar films from the 1950s and 1960s; the schedule also includes Gillo Pontecorvo’s Battle of Algiers, Stanley Kubrick’s Fear and Desire, Konrad Wolf’s I Was Nineteen, Jean-Luc Godard’s Les Carabiniers, and Peter Watkin’s The War Game, anchored by a panel discussion on January 19 at 3:00 at the Elinor Bunin Munroe Film Center (free with

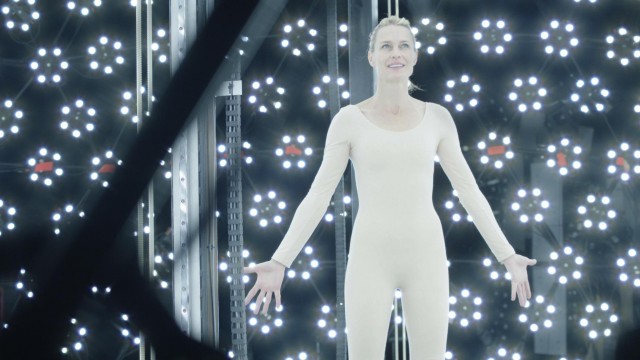

Writer-director Ari Folman imagines a sad but visually dazzling future in the spectacular fantasy The Congress. Inspired by Stanislaw Lem’s 1971 short novel The Futurological Congress, the film follows Robin Wright playing a fictionalized version of herself, an idealistic actress about to turn forty-five who has let her career come second to raising her two children, daughter Sarah (Sami Gayle) and, primarily, son Aaron (Kodi Smit-McPhee), who is slowly losing the ability to see and hear. Wright’s longtime agent, Al (Harvey Keitel), has a last-chance opportunity for her: Jeff Green (Danny Huston), the head of Miramount, wants to scan her body and emotions so the studio can manipulate her digital likeness into any role while keeping her ageless. They don’t want the modern-day Robin Wright but the young, beautiful star of The Princess Bride, State of Grace, and Forrest Gump. The only catch is that in exchange for a substantial lump-sum payment, the real Wright will never be allowed to act again, in any capacity. With no other options, she reluctantly takes the deal. Twenty years later, invited to speak at the Futurological Congress, she enters a whole new realm, a fully animated world where men, women, and children live out their entertainment fantasies. Shocked by what she is experiencing, Wright meets up with Dylan Truliner (Jon Hamm), who has been animating her digital version for years, as a revolution threatens; meanwhile, Green has another offer for her, even more frightening than the first.

Writer-director Ari Folman imagines a sad but visually dazzling future in the spectacular fantasy The Congress. Inspired by Stanislaw Lem’s 1971 short novel The Futurological Congress, the film follows Robin Wright playing a fictionalized version of herself, an idealistic actress about to turn forty-five who has let her career come second to raising her two children, daughter Sarah (Sami Gayle) and, primarily, son Aaron (Kodi Smit-McPhee), who is slowly losing the ability to see and hear. Wright’s longtime agent, Al (Harvey Keitel), has a last-chance opportunity for her: Jeff Green (Danny Huston), the head of Miramount, wants to scan her body and emotions so the studio can manipulate her digital likeness into any role while keeping her ageless. They don’t want the modern-day Robin Wright but the young, beautiful star of The Princess Bride, State of Grace, and Forrest Gump. The only catch is that in exchange for a substantial lump-sum payment, the real Wright will never be allowed to act again, in any capacity. With no other options, she reluctantly takes the deal. Twenty years later, invited to speak at the Futurological Congress, she enters a whole new realm, a fully animated world where men, women, and children live out their entertainment fantasies. Shocked by what she is experiencing, Wright meets up with Dylan Truliner (Jon Hamm), who has been animating her digital version for years, as a revolution threatens; meanwhile, Green has another offer for her, even more frightening than the first.

Nearly fifty years after the release of his first film, the short Les enfants désaccordés, post-New Wave auteur Philippe Garrel has made one of his most intimate and personal works, the deeply sensitive drama Jealousy. Garrel’s son, Louis, who has previously appeared in his father’s Regular Lovers, Frontier of the Dawn, and A Burning Hot Summer, stars as Louis, a character based on Garrel’s own father, essentially playing his own grandfather. As the film opens, Louis, an actor, is leaving his wife, Clothilde (Rebecca Convenant), for another woman, Claudia (Anna Mouglalis). A talented but unsuccessful actress, Claudia immediately bonds with Louis’s young daughter, Charlotte (Olga Milshtein). But soon jealousies of all kinds — professional, romantic, maternal, paternal, residential, and financial — affect all the characters’ desires to find happiness in life.

Nearly fifty years after the release of his first film, the short Les enfants désaccordés, post-New Wave auteur Philippe Garrel has made one of his most intimate and personal works, the deeply sensitive drama Jealousy. Garrel’s son, Louis, who has previously appeared in his father’s Regular Lovers, Frontier of the Dawn, and A Burning Hot Summer, stars as Louis, a character based on Garrel’s own father, essentially playing his own grandfather. As the film opens, Louis, an actor, is leaving his wife, Clothilde (Rebecca Convenant), for another woman, Claudia (Anna Mouglalis). A talented but unsuccessful actress, Claudia immediately bonds with Louis’s young daughter, Charlotte (Olga Milshtein). But soon jealousies of all kinds — professional, romantic, maternal, paternal, residential, and financial — affect all the characters’ desires to find happiness in life.