Vincent (newcomer Victor Ezenfis) is desperate to put his family back together in Eugène Green’s SON OF JOSEPH

THE SON OF JOSEPH (LE FILS DE JOSEPH) (Eugène Green, 2016)

Film Society of Lincoln Center

Elinor Bunin Munroe Film Center, Howard Gilman Theater

144 West 65th St. between Eighth & Amsterdam Aves.

Opens Friday, January 13

212-875-5050

www.filmlinc.org

www.kinolorber.com

Eugène Green returned to the New York Film Festival in 2016 with the glorious French satire / black comedy / biblical parable The Son of Joseph, a masterful blending of sound, image, and story that is as stunning to listen to as it is to watch. Newcomer Victor Ezenfis stars as Vincent, an intractable young teen who is desperate to discover who his father is, no matter how hard his single mother (Natacha Regnier), a nurse, tries to keep that information from him. “I don’t want to help people,” he says. “I love no one.” His sneaky ways finally reveal the man’s name, and Vincent tracks him down only to discover that the man, Oscar Pormenor (Mathieu Amalric), is a boorish, self-obsessed publisher who is cheating on his wife with his sexy secretary, Bernadette (Julia de Gasquet). At a party for his company’s latest book, The Predatory Mother, ever-so-chic critic Violette Tréfouille (Maria de Medeiros) mistakes Vincent for an up-and-coming novelist, with Oscar cluelessly declaring him the next Céline before finding out who the boy really is. Soon a disappointed Vincent is befriended by Oscar’s brother, Joseph (Fabrizio Rongione), but neither is aware of the connection. As Vincent is introduced to art and literature, he attempts to manipulate everyone around him in order to form the family he’s always wanted.

Eugène Green returned to the New York Film Festival in 2016 with the glorious French satire / black comedy / biblical parable The Son of Joseph, a masterful blending of sound, image, and story that is as stunning to listen to as it is to watch. Newcomer Victor Ezenfis stars as Vincent, an intractable young teen who is desperate to discover who his father is, no matter how hard his single mother (Natacha Regnier), a nurse, tries to keep that information from him. “I don’t want to help people,” he says. “I love no one.” His sneaky ways finally reveal the man’s name, and Vincent tracks him down only to discover that the man, Oscar Pormenor (Mathieu Amalric), is a boorish, self-obsessed publisher who is cheating on his wife with his sexy secretary, Bernadette (Julia de Gasquet). At a party for his company’s latest book, The Predatory Mother, ever-so-chic critic Violette Tréfouille (Maria de Medeiros) mistakes Vincent for an up-and-coming novelist, with Oscar cluelessly declaring him the next Céline before finding out who the boy really is. Soon a disappointed Vincent is befriended by Oscar’s brother, Joseph (Fabrizio Rongione), but neither is aware of the connection. As Vincent is introduced to art and literature, he attempts to manipulate everyone around him in order to form the family he’s always wanted.

A single mother (Natacha Regnier) has her hands full with son Vincent (Victor Ezenfis) in extraordinary biblical parable

Green, an American expatriate living and working in France — and who appears in the film as the grizzled hotel concierge — divides The Son of Joseph into five chapters named for major biblical events, including “The Sacrifice of Abraham,” “The Golden Calf,” and “The Flight to Egypt.” Vincent is mesmerized by a poster in his room of Caravaggio’s “The Sacrifice of Isaac”; at the Louvre, Joseph shows him religious paintings such as Philippe de Champaigne’s “The Dead Christ” and Georges de la Tour’s “Joseph the Carpenter.” Ever the absurdist, Green (Toutes les nuits, Le monde vivant) turns to the surreal for the finale, which features a revelation that elicited an audible gasp of wonder from the audience when I saw it, an exhalation in which I heartily participated. As in 2014’s architectural wonder La Sapienza, which also starred Rongione, each frame is composed like a work of art, courtesy of longtime Green cinematographer Raphaël O’Byrne, along with editor Valérie Loiseleux, set designer Paul Rouschop, and costume designer Agnès Noden. The entrancing color schemes and long two-shots in addition to spectacular sound by Benoît De Clerck immerse you in Green’s unique and unusual fantasy world.

The actors, who speak in Green’s trademark overly mannered and stiff style, occasionally look directly into the camera, speaking lines to the viewer, but The Son of Joseph, coproduced by Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne, never gets preachy. It’s a bizarrely entertaining tale of family, of fathers and sons, and mothers and sons, where all the details matter. Inside a church, Vincent witnesses musical ensemble Le Poème Harmonique perform a work in Latin by Domenico Mazzocchi about a mother dealing with the death of her son. Earlier, when Vincent turns down a friend’s offer to join his sperm-selling operation, it’s not merely because he might find the job distasteful; deep down, he doesn’t want any other kid to go through life not knowing who his father is. He might say, “I don’t want to help people. I love no one.” But he proves himself wrong in this stunner.

Inspired by Fatima Elayoubi’s Prayer to the Moon, a collection of writings by a Moroccan woman trying to make a new life for herself and her family in France, Philippe Faucon’s Fatima is a tender, poignant look at the immigrant experience in the twenty-first century. In her film debut, nonprofessional actress Soria Zéroual, who was discovered after a massive talent search, stars as Fatima, a traditional woman raising two daughters in a small Muslim community in France. While her children, Nesrine (Zita Hanrot), who is starting pre-med, and Souad (Kenza-Noah Aïche), a typical disenchanted teenager who prefers hanging out with her friends and flirting with boys rather than studying, speak French and dress in contemporary styles, Fatima converses primarily in Arabic and wears a head scarf. Her ex-husband (Chawki Amari) has remarried, so she has taken on the primary responsibility of raising the kids, working several jobs as a cleaning woman in order to make money to improve their lives and offer them every possibility they deserve. On the surface, Fatima is simple and plain, struggling to communicate with her daughters, her employers, and her doctors. “If my daughter’s a success, my happiness is content,” she tells Nesrine. “You drive me so mad I could go out without a head scarf,” she says to Souad. But Fatima slowly begins revealing that there is much more to her when she picks up a pen and starts sharing her deepest thoughts in a notebook, writing poetry, letters, and short pieces about her life.

Inspired by Fatima Elayoubi’s Prayer to the Moon, a collection of writings by a Moroccan woman trying to make a new life for herself and her family in France, Philippe Faucon’s Fatima is a tender, poignant look at the immigrant experience in the twenty-first century. In her film debut, nonprofessional actress Soria Zéroual, who was discovered after a massive talent search, stars as Fatima, a traditional woman raising two daughters in a small Muslim community in France. While her children, Nesrine (Zita Hanrot), who is starting pre-med, and Souad (Kenza-Noah Aïche), a typical disenchanted teenager who prefers hanging out with her friends and flirting with boys rather than studying, speak French and dress in contemporary styles, Fatima converses primarily in Arabic and wears a head scarf. Her ex-husband (Chawki Amari) has remarried, so she has taken on the primary responsibility of raising the kids, working several jobs as a cleaning woman in order to make money to improve their lives and offer them every possibility they deserve. On the surface, Fatima is simple and plain, struggling to communicate with her daughters, her employers, and her doctors. “If my daughter’s a success, my happiness is content,” she tells Nesrine. “You drive me so mad I could go out without a head scarf,” she says to Souad. But Fatima slowly begins revealing that there is much more to her when she picks up a pen and starts sharing her deepest thoughts in a notebook, writing poetry, letters, and short pieces about her life.

The Indian Point Energy Center has been fraught with controversy since it first opened in 1962 in Buchanan, New York, a mere forty-five miles from Midtown Manhattan. Documentarian Ivy Meeropol takes a close look at the past, present, and future of the embattled nuclear power plant in Indian Point, an important film that examines the complex situation from all angles. In the wake of Fukushima, eyes were once again cast at Indian Point, particularly as it approached its twenty-year recertification. Meeropol takes us inside the plant for a fascinating look at its operations, focusing on safety measures and literal and figurative cracks in the system. “This plant, in this proximity to New York City, was never a good risk,” Gov. Cuomo says in a press conference at the beginning of the film. Men and women on multiple sides of the issue speak with Meeropol, offering their take on what is happening. “Everyone has their fingers crossed under the table and they’re, like, let’s just hope nobody fucks up and they don’t have an accident,” says lawyer Phillip Musegaas of the watchdog organization Riverkeeper, which defends and protects the Hudson River. “We try to minimize that risk as much as we can. That’s our job,” explains Brian Vangor, a senior control room operator who has been working at Indian Point for more than thirty-five years. Somewhere in the middle is environmental journalist Roger Witherspoon, who notes, “For those who work in the nuclear industry, this is a ‘safe’ plant. For those who don’t work in the nuclear industry, there are risks you don’t want to live with.” Witherspoon is married to Marilyn Elie, a fierce activist who is part of IPSEC, the Indian Point Safe Energy Coalition. But the most interesting individual in the film is Gregory Jaczko, who at the time of filming was the chairman of the Nuclear Regulatory Commission and faces stiff opposition from within when he starts questioning Indian Point’s recertification.

The Indian Point Energy Center has been fraught with controversy since it first opened in 1962 in Buchanan, New York, a mere forty-five miles from Midtown Manhattan. Documentarian Ivy Meeropol takes a close look at the past, present, and future of the embattled nuclear power plant in Indian Point, an important film that examines the complex situation from all angles. In the wake of Fukushima, eyes were once again cast at Indian Point, particularly as it approached its twenty-year recertification. Meeropol takes us inside the plant for a fascinating look at its operations, focusing on safety measures and literal and figurative cracks in the system. “This plant, in this proximity to New York City, was never a good risk,” Gov. Cuomo says in a press conference at the beginning of the film. Men and women on multiple sides of the issue speak with Meeropol, offering their take on what is happening. “Everyone has their fingers crossed under the table and they’re, like, let’s just hope nobody fucks up and they don’t have an accident,” says lawyer Phillip Musegaas of the watchdog organization Riverkeeper, which defends and protects the Hudson River. “We try to minimize that risk as much as we can. That’s our job,” explains Brian Vangor, a senior control room operator who has been working at Indian Point for more than thirty-five years. Somewhere in the middle is environmental journalist Roger Witherspoon, who notes, “For those who work in the nuclear industry, this is a ‘safe’ plant. For those who don’t work in the nuclear industry, there are risks you don’t want to live with.” Witherspoon is married to Marilyn Elie, a fierce activist who is part of IPSEC, the Indian Point Safe Energy Coalition. But the most interesting individual in the film is Gregory Jaczko, who at the time of filming was the chairman of the Nuclear Regulatory Commission and faces stiff opposition from within when he starts questioning Indian Point’s recertification.

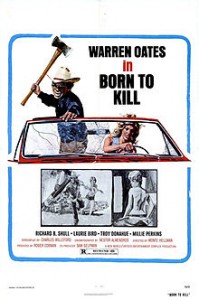

Director Monte Hellman and star Warren Oates enter “the mystic realm of the great cock” in the 1974 cult film Cockfighter. Alternately known as Born to Kill and Gamblin’ Man, the film is set in the world of cockfighting, where Frank Mansfield (Oates) is trying to capture the Cockfighter of the Year award following a devastating loss that cost him his money, car, trailer, girlfriend, and voice — he took a vow of silence until he wins the coveted medal. Mansfield communicates with others via his own made-up sign language and by writing on a small pad; in addition, he delivers brief internal monologues in occasional voiceovers. He teams up with moneyman Omar Baradansky (Richard B. Shull) as he attempts to regain his footing in the illegal cockfighting world, taking on such challengers as Junior (Steve Railsback), Tom (Ed Begley Jr.), and archnemesis Jack Burke (Harry Dean Stanton); his drive for success is also fueled by his desire to finally marry his much-put-upon fiancée, Mary Elizabeth (Patricia Pearcy). The cast also includes Laurie Bird as Mansfield’s old girlfriend, Troy Donahue as his brother, Millie Perkins as his sister-in-law, Warren Finnerty as Sanders, Allman Brothers guitarist Dickey Betts as a masked robber, and Charles Willeford, who wrote the screenplay based on his novel, as Ed Middleton.

Director Monte Hellman and star Warren Oates enter “the mystic realm of the great cock” in the 1974 cult film Cockfighter. Alternately known as Born to Kill and Gamblin’ Man, the film is set in the world of cockfighting, where Frank Mansfield (Oates) is trying to capture the Cockfighter of the Year award following a devastating loss that cost him his money, car, trailer, girlfriend, and voice — he took a vow of silence until he wins the coveted medal. Mansfield communicates with others via his own made-up sign language and by writing on a small pad; in addition, he delivers brief internal monologues in occasional voiceovers. He teams up with moneyman Omar Baradansky (Richard B. Shull) as he attempts to regain his footing in the illegal cockfighting world, taking on such challengers as Junior (Steve Railsback), Tom (Ed Begley Jr.), and archnemesis Jack Burke (Harry Dean Stanton); his drive for success is also fueled by his desire to finally marry his much-put-upon fiancée, Mary Elizabeth (Patricia Pearcy). The cast also includes Laurie Bird as Mansfield’s old girlfriend, Troy Donahue as his brother, Millie Perkins as his sister-in-law, Warren Finnerty as Sanders, Allman Brothers guitarist Dickey Betts as a masked robber, and Charles Willeford, who wrote the screenplay based on his novel, as Ed Middleton.