Marcel Duchamp, “Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2),” oil on canvas, 1912 (Philadelphia Museum of Art: The Louise and Walter Arensberg Collection)

New-York Historical Society

170 Central Park West at Richard Gilder Way (77th St.)

Daily through February 23, $18 (pay-as-you-wish Friday 6:00 – 8:00)

212-873-3400

www.armory.nyhistory.org

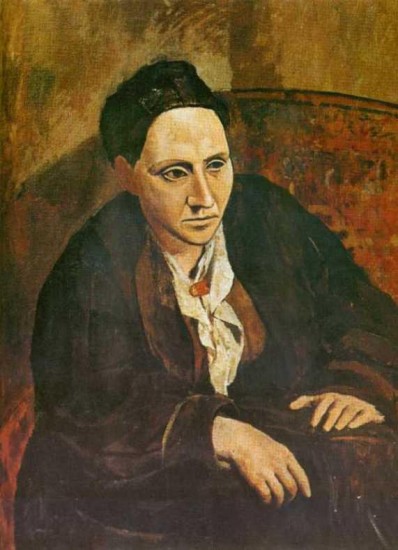

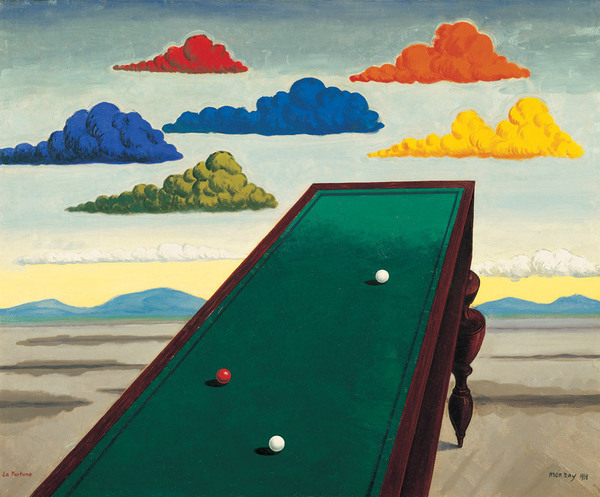

It was a seminal moment in the way contemporary art was introduced to the American public. “New York will never be the same again,” Arthur B. Davies said, while Walt Kuhn proclaimed, “We will show New York something they never dreamed of.” On February 17, 2013, the Armory Show opened at the 69th Regiment Armory on Lexington Ave. and Twenty-Sixth St.; organized by the Association of American Painters and Sculptors, which was headed by Davies, the show brought the European avant-garde to the America public. The New-York Historical Society is celebrating the transformative event’s centennial with “The Armory Show at 100: Modern Art and Revolution,” a wide-ranging exhibition that includes approximately one hundred works from the original presentation, by such innovative and influential European artists as Marcel Duchamp, Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, Constantin Brancusi, Paul Cézanne, Vincent van Gogh, Edgar Degas, Paul Gauguin, Odilon Redon, and Edvard Munch in addition to such American painters and sculptors as Childe Hassam, George Bellows, Stuart Davis, James McNeill Whistler, Albert Pinkham Ryder, John Sloan, and Charles R. Sheeler. “The Armory Show at 100” delves into the fascinating behind-the-scenes battles between Davies, Kuhn, J. Alden Weir, Walter Pach, Guy Pène du Bois, and the National Academy through quotes, postcards, and letters that detail the controversial selection process and purpose of the show while also placing it firmly within the context of the sociopolitical climate and evolving culture (including literature and film) of early-twentieth-century New York City as WWI loomed on the horizon.

Albert Pinkham Ryder, “Pastoral Study,” oil on canvas mounted on fiberboard, 1897 (Smithsonian American Art Museum)

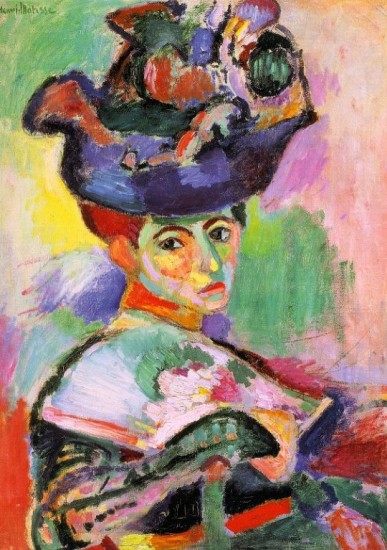

Many of the works on view, arranged thematically in clever ways, are simply sensational: Duchamp’s “Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2),” Matisse’s “Blue Nude,” “The Red Studio,” and “Goldfish and Sculpture,” van Gogh’s “Mountains at Saint-Rémy” and “La salle de danse à Arles,” Redon’s “Silence,” Bellows’s “Circus,” Ryder’s “Pastoral Study,” Eugène Delacroix’s “Christ on the Lake of Genesareth,” Degas’s “After the Bath,” Munch’s “Madonna,” Charles Henry White’s “The Condemned Tenement,” and Francis Picabia’s “The Procession, Seville.” The free audioguide adds additional insight to the lasting importance of “The Armory Show,” while the catalog features thirty-one essays, with contributions from curators Marilyn Kushner and Kimberly Orcutt along with Leon Botstein, Avis Berman, Barbara Haskell, Francis M. Naumann, Casey Nelson Blake, and others. “Criticism, both for and against modern art in the exhibition — now considered one of the most important art exhibitions ever mounted in the United States — was impassioned, and it seemed as if everyone from the most seasoned collector or established artist to the uninitiated viewer had an opinion,” Kushner writes in her piece, “A Century of the Armory Show: Modernism and Myth.” The thoughtful, well-organized show continues through February 23, with timed tickets available in advance, which is definitely the way to go to avoid the lines. As a bonus, the New-York Historical Society will be open on Monday, February 17. (Next month, the Armory Show comes back to town, running March 6-9 at Piers 92 and 94 as part of Armory Arts Week, but it’s nothing like its namesake.)