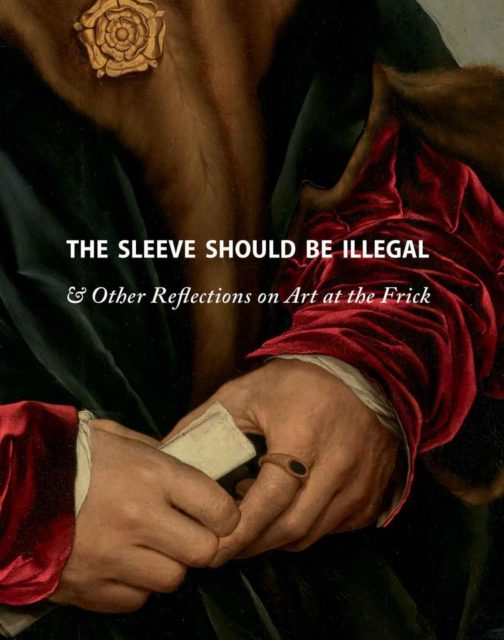

El Greco’s St. Jerome is once again flanked by Hans Holbein the Younger’s Sir Thomas More and Thomas Cromwell (photo by twi-ny/mdr)

THE FRICK COLLECTION

1 East 70th St. at Fifth Ave.

Wednesday – Sunday, $17-$30 (pay-what-you-wish Wednesdays 2:00–6:00)

www.frick.org

The Frick is my happy place.

Judging by the smiles on the faces of the hundreds of other Fricksters I encountered at a recent members preview of the reopened Fifth Ave. institution, I am far from the only one.

In 1913, American industrialist and art collector Henry Clay Frick commissioned the architecture firm of Carrère and Hastings to design the building as both a private home and a public resource. Frick died in 1919 at the age of sixty-nine; his daughter, Helen Clay Frick, served as a founding trustee of the collection and, in 1920, established the Frick Art Reference Library. In 1931, the building was adapted into a museum by architect John Russell Pope. The Frick Collection opened on December 11, 1935, for distinguished guests; three days later, ARTnews editor Alfred M. Frankfurter wrote that it is “one of the most important events in the history of American collecting and appreciation of art.”

The Frick closed in March 2020 for a major renovation, temporarily moving its remarkable holdings to the nearby Breuer Building on Seventy-Fifth and Madison, the former home of the Whitney. On April 17, the Frick will reopen to the public, with ten percent more square footage, going from 178,000 square feet to 196,000, including 60,000 square feet of repurposed space and 27,000 square feet of new construction, increasing the gallery space by thirty percent, highlighted by the unveiling of the second floor, which has been converted from administrative offices to fifteen rooms of masterpieces. The renovation and revitalization also features a new Reception Hall, Education Room, and 218-seat auditorium.

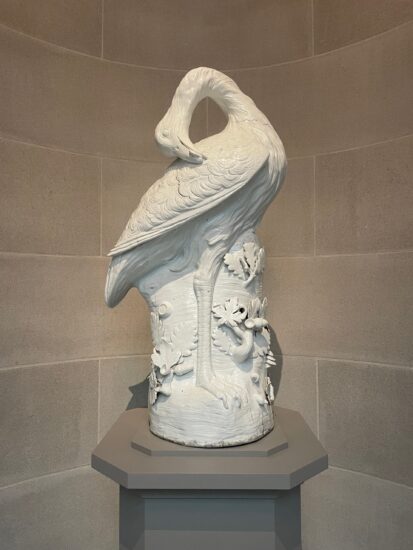

The 1732 Great Bustard resides on a pedestal near the Garden Court fountain (photo by twi-ny/mdr)

The main floor will be familiar to anyone who has ever visited the Frick; amid some minor changes, the twenty rooms have remained mostly intact. The Gainsboroughs are in the Dining Room, Boucher’s The Four Seasons are in the West Vestibule, four Whistler portraits stand tall in the Oval Room, Fragonard’s The Progress of Love series populates the Fragonard Room, and Goya’s Portrait of a Lady (María Martínez de Puga?) brings mystery to the East Gallery.

El Greco’s Purification of the Temple can be found in the Anteroom, Tiepolo’s Perseus and Andromeda in the East Vestibule, and Vecchietta’s The Resurrection in the Octagon Room. John C. Johansen’s portrait of Henry Clay Frick enjoys primo placement in the Library, where he is joined by Gilbert Stuart’s 1795 portrait of George Washington and numerous canvases by such British artists as Reynolds, Gainsborough, Romney, Turner, and Constable, whose Salisbury Cathedral from the Bishop’s Grounds has delighted me over and over again.

The Garden Court, with its peaceful fountain surrounded by columns, plantings, and Barbet’s Angel, is one of the loveliest indoor respites in the city.

Velázquez’s King Philip IV of Spain and Goya’s The Forge hang catty corner in the West Gallery (photo by twi-ny/mdr)

The glorious West Gallery houses many of the greatest hits, from Rembrandt’s stunning 1658 Self-Portrait and Velázquez’s regal King Philip IV of Spain to Goya’s gritty The Forge and Veronese’s enigmatic parable The Choice Between Virtue and Vice, along with a pair of gorgeous Turner port scenes, Corot’s captivating landscape The Lake, Vermeer’s Mistress and Maid, portraits by El Greco, Hals, Goya, and Van Dyke, and more than a dozen small mythological sculptures.

Bellini’s St. Francis in the Desert no longer has its own room but is coping (photo by twi-ny/mdr)

The centerpiece of the Frick has always been the Living Hall, with magisterial furniture, chandeliers, large vases, and a five-hundred-year-old Persian carpet. On one wall, Titian’s Pietro Aretino and Portrait of a Man in a Red Hat flank Bellini’s St. Francis in the Desert, which in the Frick Madison had its own room. Opposite that trio is the pièce de résistance: El Greco’s elongated St. Jerome stares out above the fireplace; to his left and right, respectively, are Hans Holbein the Younger’s stunning portraits of archenemies Thomas Cromwell and Sir Thomas More, the latter, in my opinion, the most spectacular portrait in the history of Western art. Its name, the Living Hall, could not be more appropriate, as it feels lived in.

Drouais’s The Comte and Chevalier de Choiseul as Savoyards is near the base of the stairs (photo by twi-ny/mdr)

The South Hall offers two Vermeers, Girl Interrupted at Her Music and Officer and Laughing Girl, facing a Frick fan favorite, Bronzino’s Lodovico Capponi, with its cleverly placed sword. After years of appearing behind the ropes that bar visitors from going upstairs, Drouais’s The Comte and Chevalier de Choiseul as Savoyards, depicting two young boys smiling like the cat who ate the canary, can now be approached before you make your pilgrimage to newly sanctified land.

And then, there it is: the Grand Stairway leading to the previously off-limits second floor. The looks as people make their way to the steps are fascinating, a mix of bated breath, yearning, excited anticipation, and even stealth, as if some museumgoers still can’t believe it is allowed. At the landing is a decorative screen and an Aeolian-Skinner organ that was once played by Archer Gibson for Henry and at dinner parties. At the top is Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s La Promenade, a lush oil of a woman and two young twin sisters that used to reside near the base of the stairs and now serves as a fine introduction to the myriad treasures upstairs.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s La Promenade greets visitors at the top of the Grand Stairway (photo by twi-ny/mdr)

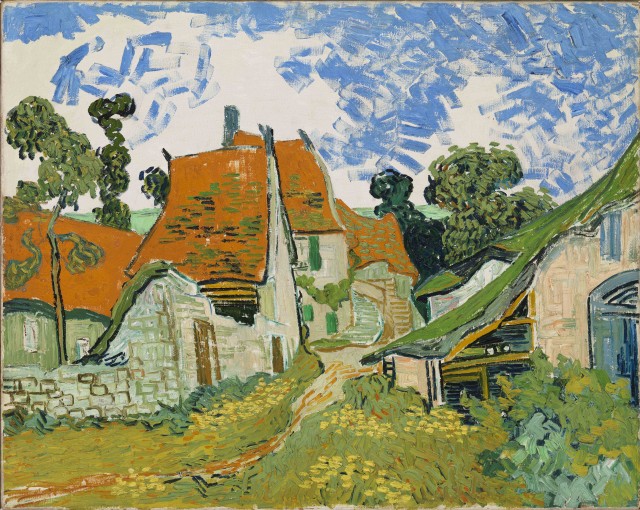

The second floor is a mazelike procession of tighter spaces where the Fricks lived, again adorned with dazzling classics and lesser-known works that were not regularly on view in the past. Corot’s Ville-d’Avray and The Pond are in the Breakfast Room, with sets of jars and wine coolers and Théodore Rousseau’s The Village of Becquigny. Manet’s The Bullfight can now be found in the Impressionist Room, joined by Degas’s The Rehearsal and Monet’s Vétheuil in Winter, which had numerous people gasping. “I don’t remember ever seeing this before,” one woman said, and others nodded. Don’t miss Watteau’s The Portal of Valenciennes in the Small Hallway.

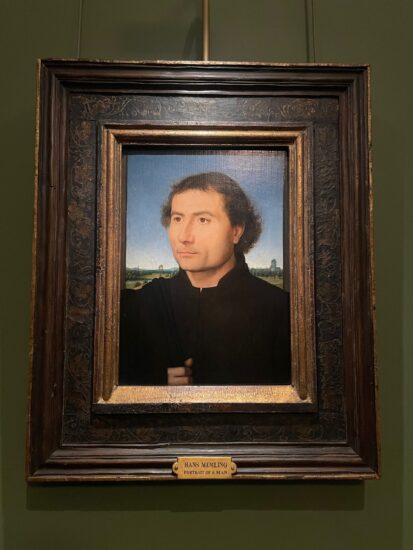

Hans Memling’s Portrait of a Man is now upstairs in the Sitting Room at the Frick (photo by twi-ny/mdr)

The Gold-Grounds Room gathers such religious works as Fra Filippo Lippi’s The Annunciation, Piero della Francesca’s The Crucifixion, and Paolo Veneziano’s The Coronation of the Virgin. Although there is a user-friendly app that tells you where everything is, I preferred searching on my own and was thrilled when I finally located Hans Memling’s Portrait of a Man in the Sitting Room, a depiction of an invitingly calm, laid-back man. Ingres’s Louise, Princesse de Broglie, Later the Comtesse d’Haussonville, another Frick fave, now holds court in the Walnut Room, near Houdon’s marble Madame His.

Among the other second-floor galleries are the Clocks and Watches Room, the Du Paquier Passage, the Boucher Room and Anteroom, the Ceramics Room, the Medals Room, and the Lajoue Passage, each with their own charm. And be sure to check out the hallway ceilings, covered in a beautiful mural with fabulous detail in the corners and ends.

The corners of the second-floor ceiling murals hold tiny gems (photo by twi-ny/mdr)

As recently retired former Frick director Ian Waldropper notes in the Frick’s Essential Guide, “The reopening of the renovated Frick Collection is cause for celebration.” It’s an inspiring place to visit old friends and make new ones, to see masterpieces in literal and figurative new light. One way the Frick has not changed is that the institution still does not allow any photos or videos, except at the early members and press previews. At first, I wasn’t going to take any pictures, but then I heard a few guards say, “Get out your cameras now, because you won’t be allowed to starting April 17.”

My happy place is back, and just in time.

There are two current special exhibitions; “Highlights of Drawings from the Frick Collection,” continuing in the Cabinet through August 11, consists of a dozen rarely displayed works, from Pisanello’s haunting pen and brown ink Studies of Men Hanging and Whistler’s surprising black chalk and pastel Venetian Canal to Goya’s brush and brown wash The Anglers and the coup de grâce, Ingres’s graphite and black chalk study for Louise, Princesse de Broglie . . .

Vladimir Kanevsky’s porcelain hydrangeas can be found in the Breakfast Room (photo by twi-ny/mdr)

Meanwhile, for “Porcelain Garden,” US-based Ukrainian artist Vladimir Kanevsky has installed porcelain flowers in nineteen locations throughout the Frick, on the floor and on tables, in vases and pots, creating a dialogue between the fragile plants and the museum’s many treasures; you’ll find lilacs in the Dining Room, foxgloves in the West Vestibule, cascading roses and white hyacinths in the Fragonard Room, dahlia branches and anemones in the Portico Gallery, and a lemon tree in the Garden Court, among others.

And from June 18 to August 31, “Vermeer’s Love Letters” unites the Frick’s Mistress and Maid with the Rijksmuseum’s Love Letter and the National Gallery of Ireland’s Woman Writing a Letter, with Her Maid.

Below are only some of the scheduled programs, with more to come.

Friday, April 18

Gallery Talk: A Home for Art, Library Gallery, free with museum admission, 6:00 & 7:00

Gallery Talk: Closer Look at Vermeer’s Mistress and Maid, West Gallery, free with museum admission, 6:00 & 7:00

Friday, April 25

Gallery Talk: A Home for Art, Library Gallery, free with museum admission, 6:00 & 7:00

Saturday, April 26

Spring Music Festival: Jupiter Ensemble, Lea Desandre, Anthony Roth Costanzo, Stephen A. Schwarzman Auditorium, 7:00

Thursday, May 1

Spring Music Festival: Takács Quartet and Jeremy Denk, Piano, Stephen A. Schwarzman Auditorium, 7:00

Saturday, May 3

Spring Music Festival: Sarah Rothenberg, Solo Piano, Stephen A. Schwarzman Auditorium, 7:00

Sunday, May 4

Spring Music Festival: Alexi Kenney, Violin and Amy Yang, Fortepiano, Stephen A. Schwarzman Auditorium, 7:00

Thursday, May 8

Sketch Night, free with advance RSVP, 5:00

Spring Music Festival: Emi Ferguson, Flute and Ruckus, Baroque Ensemble, Stephen A. Schwarzman Auditorium, 7:00

Friday, May 9

Stephen K. and Janie Woo Scher Fellow Lecture: The Milicz Medals of Johann Friedrich of Saxony and the Subtleties of Political Art in the Age of Reformation, with Maximilian Kummer, Ian Wardropper Education Room, free with advance RSVP, 6:00

Sunday, May 11

Spring Music Festival: Mishka Rushdie Momen, Solo Piano, Stephen A. Schwarzman Auditorium, 5:00

[Mark Rifkin is a Brooklyn-born, Manhattan-based writer and editor; you can follow him on Substack here.]