CHOP SUEY (Bruce Weber, 2001)

Film Forum

209 West Houston St.

Sunday, November 3, 8:15

Wednesday, November 6, 8:50

Series runs November 1-7

212-727-8110

www.filmforum.org

www.bruceweber.com

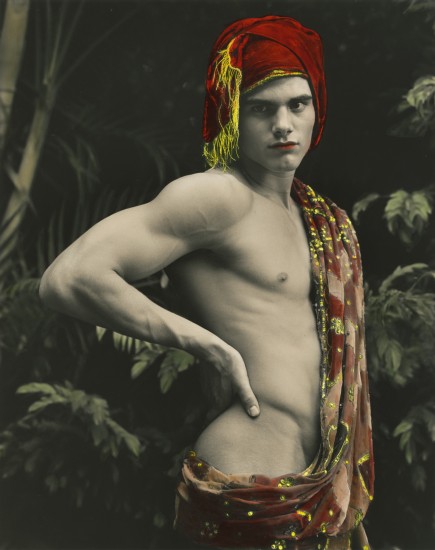

Fashion photographer Bruce Weber, who directed the seminal Chet Baker doc Let’s Get Lost a quarter century ago, made this entertaining hodgepodge of still photos, old color and black-and-white footage, and new interviews and voice-over narration back in 2001. You might not know much about Frances Faye, but after seeing her perform in vintage Ed Sullivan clips and listening to her manager/longtime partner discuss their life together, you’ll be searching YouTube to check out a lot more. The film also examines how Weber selects and treats his male models, who are often shot in homoerotic poses for major designers (and later go on to get married and have children). As a special treat, Jan-Michael Vincent’s extensive full-frontal nude scene in Daniel Petrie and Sidney Sheldon’s 1974 Buster and Billie is on display here, as are vintage clips of Sammy Davis Jr., adventurer Sir Wilfred Thesiger, former Vogue editor Diana Vreeland, and Robert Mitchum singing in a recording studio with Dr. John.

The film is about model Peter Johnson and Weber as much as it is about the cult of celebrity; Weber gets to chime in on Elizabeth Taylor, Montgomery Clift, Clark Gable, Frank Sinatra, Arthur Miller, and dozens of other famous names and faces. Though an awful lot of fun, the film is disjointed, lacking a central focus, and the onscreen titles, end credits, and promotional postcards are chock-full of typos — perhaps emulating a Chinese takeout menu, hence the film’s title? Chop Suey is screening November 3 at 8:15, followed by a Q&A with Peter Johnson, and November 7 at 8:50 as part of Film Forum’s “Bruce Weber” series, which runs November 1-7 and also includes a new 4K restoration of Let’s Get Lost, followed by a talk with cinematographer Jeff Preiss; 1987’s Broken Noses, about former Olympian boxer Andy Minsker; 2018’s Nice Girls Don’t Stay for Breakfast, followed by a conversation with Carrie Mitchum and editor Chad Sipkin; 2004’s A Letter to True, a tribute to Weber’s dog; a compilation of shorts, videos, commercials, and works in progress; and The Treasure of His Youth: The Photographs of Paolo di Paolo.

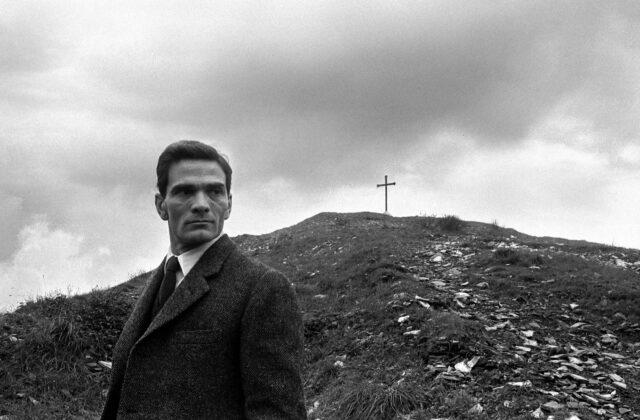

Paolo di Paolo’s photograph of Pier Paolo Pasolini at Monte dei Cocci in 1960 is one of many highlighted in Bruce Weber documentary

THE TREASURE OF HIS YOUTH: THE PHOTOGRAPHS OF PAOLO DI PAOLO (Bruce Weber, 2022)

Saturday, November 2, 1:00

www.filmforum.org

“The mystery of Paolo di Paolo to me is that he was able to give up photography, something he once had such passion for,” documentarian Bruce Weber says at the beginning of the fabulous The Treasure of His Youth: The Photographs of Paolo di Paolo, a warm and inviting film about one of the greatest photographers you’ve never heard of.

In 1954, Italian philosopher Paolo di Paolo saw a Leica III camera in a shop window and, at the spur of the moment, decided to buy it. That led to fourteen extraordinary years during which the self-taught artist took pictures for Il Mondo and Il Tempo, documenting, primarily in black-and-white, postwar Italy as well as the country’s burgeoning film industry. He was not about glitz and glamour; he captured such figures as Luchino Visconti, Anna Magnani, Ezra Pound, Simone Signoret, Marcello Mastroianni, Charlotte Rampling, Alberto Moravia, Sofia Loren, Giorgio Di Chirico, and others in private moments and glorying in bursts of freedom. He went on a road trip with Pier Paolo Pasolini for a magazine story in which the director would write the words and di Paolo would supply the images. His photos of the society debut of eighteen-year-old Princess Pallavincini are poignant and beautiful, nothing like standard publicity shots.

Paolo di Paolo’s relationship with the camera is revealed in lovely documentary (photo courtesy Little Bear Films)

Then, in 1968, just as suddenly as he picked up the camera, he put it away, frustrated by the growing paparazzi culture and television journalism. A few years ago, Weber and his wife went into a small gallery in Rome where Weber, who has had a “love affair” with Rome since he was ten, discovered magnificent photos of many of his favorite Italian film stars. The gallery owner, Giuseppe Casetti, told him that the pictures were by an aristocratic gentleman he had bumped into at flea markets and who one day came into the bookstore where he was working and gave him one for free, knowing he was a collector. Casetti wanted to know who had taken the photo; “I was once a photographer,” di Paolo told him unassumingly.

That set Weber off on a search to find out everything he could about di Paolo, who is now ninety-seven. Even his daughter, Silvia di Paolo, had no knowledge of her father’s past as a photographer until she found nearly a quarter of a million negatives in the basement of the family home and began organizing them about twenty years ago. Paolo had never spoken of this part of his life; he wrote books on philosophy, was the official historian of the Carabinieri, and restored antique sports cars, but his artistic career was an enigma even though it was when he met his wife, his former assistant.

The father of the bride watches the young couple as they head down a country road (photo by Paolo di Paolo)

Weber follows di Paolo as he meets with photographer Tony Vaccaro, film producer Marina Cigona, and his longtime friend (but not related) Antonio do Paola, visits his childhood home in Larino, is interviewed by the young son of Vogue art director Luca Stoppini, and attends his first-ever retrospective exhibition (“Il Mondo Perduto” at the Maxxi Museum in Rome). And he picks up the camera again, taking photos at a Valentino fashion show.

Cinematographer Theodore Stanley evokes di Paolo’s unpretentious style as he photographs the aristocratic gentleman walking up a narrow cobblestoned street, his cane in his right hand, an umbrella in his left over his head, and driving one of his sports cars. Editor and cowriter Antonio Sánchez intercuts hundreds and hundreds of di Paolo’s photos, several of which are discussed in the film: a spectacular shot of Pasolini at Monte dei Cocci, the director in the foreground, the famous cross atop a hill in the background; Visconti in a chair, fanning himself; a scene in which a father, hands in his pocket, watches his daughter and new son-in-law walking away on an empty country road. There are also clips from such classic films as Rocco and His Brothers, Accatone, Rome Open City, Marriage Italian Style, and 8½. It’s all accompanied by John Leftwich’s epic score.

As Cigona tells di Paolo about having ended his flourishing photography career, “People said, ‘Why did you do that? You were quite famous.’” It was never about the fame for di Paolo, but now the secret is out.

“For me, every object is a miracle,” Pasolini says in an archival interview. In The Treasure of His Youth, Weber treats every moment with di Paolo and his photographs as a miracle. So will you.

[Mark Rifkin is a Brooklyn-born, Manhattan-based writer and editor; you can follow him on Substack here.]

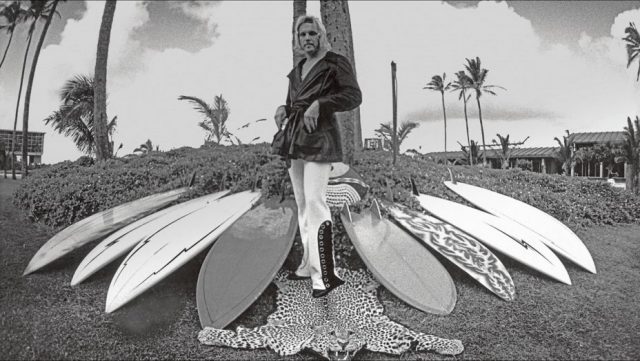

Former Japanese national surfing champion Takuji Masuda documents the wild life and times of sugar scion Bunker Spreckels in the bumpy, oddly titled Bunker77, which is having its New York City premiere November 16 and 17 at the DOC NYC festival. Born in Los Angeles in 1949, Spreckels is described in the film by friends and relatives as “radical,” “original,” “unique,” “dangerous,” and “fun,” a blond beach bum and party lover who rode waves around the world with his specially made short boards. “That was his international persona: the hunter, the surfer, the playboy, the jet-setter, the martial artist, all in one,” skateboard legend Tony Alva says of his friend and mentor. Spreckels’s grandfather, Adolph B. Spreckels, ran the Spreckels Sugar Company and, with his wife, Alma, helped develop the cities of San Francisco and San Diego. After Spreckels’s parents, Adolph B. Spreckels II and former actress Kay Williams, divorced, his mother married Clark Gable, who helped raise Bunker and his sister, Joan, for five years. Bunker always did things his own way, but his life spiraled out of control once he turned twenty-one and gained access to his multimillion-dollar trust fund, caught up in a storm of drugs, alcohol and women. He tried to become a rock star and a screen idol while skateboarding and surfing in California, Hawai’i, Australia, and South Africa. His story is told by such surfing legends as Laird Hamilton, Vinny Bryan, Bill Hamilton, Rory Russell, Nat Young, Herbie Fletcher, Spyder Wills, and Wayne Bartholomew; childhood friends Curtis Allen (son of cowboy movie star Rex Allen) and Ira Opper; Surfer magazine photographer Art Brewer, associate editor Kurt Ledterman, chief editor Drew Kampion, and publisher Steve Pezman; longtime girlfriend Ellie Silva; and journalist C. R. Steyck III, whose extensive interview with Spreckels near the end of his life is sprinkled throughout the documentary. Masuda also includes home movies, photographs, relevant clips from Gable films, and scenes from 2005’s Lords of Dogtown, in which Johnny Knoxville plays Topper Burks, who is based on Spreckels, and 1961’s Blue Hawaii, in which Elvis Presley plays a character eerily similar to Bunker. “You can definitely have too much fun with too much money,” Bartholomew says, while Steyck adds, “He was a dangerous man, mainly dangerous to himself.”

Former Japanese national surfing champion Takuji Masuda documents the wild life and times of sugar scion Bunker Spreckels in the bumpy, oddly titled Bunker77, which is having its New York City premiere November 16 and 17 at the DOC NYC festival. Born in Los Angeles in 1949, Spreckels is described in the film by friends and relatives as “radical,” “original,” “unique,” “dangerous,” and “fun,” a blond beach bum and party lover who rode waves around the world with his specially made short boards. “That was his international persona: the hunter, the surfer, the playboy, the jet-setter, the martial artist, all in one,” skateboard legend Tony Alva says of his friend and mentor. Spreckels’s grandfather, Adolph B. Spreckels, ran the Spreckels Sugar Company and, with his wife, Alma, helped develop the cities of San Francisco and San Diego. After Spreckels’s parents, Adolph B. Spreckels II and former actress Kay Williams, divorced, his mother married Clark Gable, who helped raise Bunker and his sister, Joan, for five years. Bunker always did things his own way, but his life spiraled out of control once he turned twenty-one and gained access to his multimillion-dollar trust fund, caught up in a storm of drugs, alcohol and women. He tried to become a rock star and a screen idol while skateboarding and surfing in California, Hawai’i, Australia, and South Africa. His story is told by such surfing legends as Laird Hamilton, Vinny Bryan, Bill Hamilton, Rory Russell, Nat Young, Herbie Fletcher, Spyder Wills, and Wayne Bartholomew; childhood friends Curtis Allen (son of cowboy movie star Rex Allen) and Ira Opper; Surfer magazine photographer Art Brewer, associate editor Kurt Ledterman, chief editor Drew Kampion, and publisher Steve Pezman; longtime girlfriend Ellie Silva; and journalist C. R. Steyck III, whose extensive interview with Spreckels near the end of his life is sprinkled throughout the documentary. Masuda also includes home movies, photographs, relevant clips from Gable films, and scenes from 2005’s Lords of Dogtown, in which Johnny Knoxville plays Topper Burks, who is based on Spreckels, and 1961’s Blue Hawaii, in which Elvis Presley plays a character eerily similar to Bunker. “You can definitely have too much fun with too much money,” Bartholomew says, while Steyck adds, “He was a dangerous man, mainly dangerous to himself.”

It’s hard to believe that the Hays Code, a set of standards initiated by two religious figures and named after chief censor Will H. Hays, was enacted and enforced, to varying degrees, in Hollywood from 1934 all the way up to 1968. One of the best examples of the racier pre-code films is William A. Wellman’s rarely screened 1931 doozy, Night Nurse. The first of five collaborations between Wellman and Barbara Stanwyck, Night Nurse, based on Dora Macy’s 1930 novel, stars Stanwyck as Lora Hart, a young woman determined to become a nurse. She gets a probationary job at a city hospital, where she is taken under the wing of Maloney (Joan Blondell), who likes to break the rules and torture the head nurse, the stodgy Miss Dillon (Vera Lewis). Shortly after treating a bootlegger (Ben Lyon) for a gunshot wound and agreeing not to report it to the police, Lora starts working for a shady doctor (Ralf Harolde) taking care of two sick children (Marcia Mae Jones and Betty Jane Graham) whose proudly dipsomaniac mother (Charlotte Merriam) is being manipulated by her suspicious chauffeur (Clark Gable). Wellman pulls out all the stops, hinting at or simply depicting murder, child endangerment, rape, alcoholism, lesbianism, physical brutality, and Blondell and Stanwyck regularly frolicking around in their undergarments. It’s as if Wellman is thumbing his nose directly at the upcoming Hays Code in scene after scene. Although far from his best film — Wellman directed such classics as Wings (1927), The Public Enemy (1931), A Star Is Born (1937), Nothing Sacred (1937), Beau Geste (1939), and The Ox-Bow Incident (1943) — Night Nurse is an overly melodramatic, dated, but entertaining little tale with quite a surprise ending. Night Nurse is screening July 11 as part of the Rubin Museum’s Cabaret Cinema series “Movie Medicine: A Film Series about the Healing Factor in Cinema,” being held in conjunction with the “Bodies in Balance: The Art of Tibetan Medicine” exhibition, and will be introduced by Edna Igoe of the New York Professional Nurses Union. The series continues July 18 with Woody Allen’s Sleeper, introduced by psychotherapist Maggie Robbins, July 25 with Arthur Hiller’s The Hospital, introduced by Dr. Kenneth Perrine, and August 1 with Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s Black Narcissus, introduced by award-winning editor Thelma Schoonmaker.

It’s hard to believe that the Hays Code, a set of standards initiated by two religious figures and named after chief censor Will H. Hays, was enacted and enforced, to varying degrees, in Hollywood from 1934 all the way up to 1968. One of the best examples of the racier pre-code films is William A. Wellman’s rarely screened 1931 doozy, Night Nurse. The first of five collaborations between Wellman and Barbara Stanwyck, Night Nurse, based on Dora Macy’s 1930 novel, stars Stanwyck as Lora Hart, a young woman determined to become a nurse. She gets a probationary job at a city hospital, where she is taken under the wing of Maloney (Joan Blondell), who likes to break the rules and torture the head nurse, the stodgy Miss Dillon (Vera Lewis). Shortly after treating a bootlegger (Ben Lyon) for a gunshot wound and agreeing not to report it to the police, Lora starts working for a shady doctor (Ralf Harolde) taking care of two sick children (Marcia Mae Jones and Betty Jane Graham) whose proudly dipsomaniac mother (Charlotte Merriam) is being manipulated by her suspicious chauffeur (Clark Gable). Wellman pulls out all the stops, hinting at or simply depicting murder, child endangerment, rape, alcoholism, lesbianism, physical brutality, and Blondell and Stanwyck regularly frolicking around in their undergarments. It’s as if Wellman is thumbing his nose directly at the upcoming Hays Code in scene after scene. Although far from his best film — Wellman directed such classics as Wings (1927), The Public Enemy (1931), A Star Is Born (1937), Nothing Sacred (1937), Beau Geste (1939), and The Ox-Bow Incident (1943) — Night Nurse is an overly melodramatic, dated, but entertaining little tale with quite a surprise ending. Night Nurse is screening July 11 as part of the Rubin Museum’s Cabaret Cinema series “Movie Medicine: A Film Series about the Healing Factor in Cinema,” being held in conjunction with the “Bodies in Balance: The Art of Tibetan Medicine” exhibition, and will be introduced by Edna Igoe of the New York Professional Nurses Union. The series continues July 18 with Woody Allen’s Sleeper, introduced by psychotherapist Maggie Robbins, July 25 with Arthur Hiller’s The Hospital, introduced by Dr. Kenneth Perrine, and August 1 with Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s Black Narcissus, introduced by award-winning editor Thelma Schoonmaker.

Fashion photographer Bruce Weber, who directed the seminal Chet Baker doc Let’s Get Lost a quarter century ago, made this fun hodgepodge of still photos, old color and black-and-white footage, and new interviews and voice-over narration back in 2001. You might not know much about Frances Faye, but after seeing her perform in vintage Ed Sullivan clips and listening to her manager/longtime partner discuss their life together, you’ll be searching YouTube to check out a lot more. The film also examines how Weber selects and treats his male models, who are often shot in homoerotic poses for major designers (and later go on to get married and have children). As a special treat, Jan-Michael Vincent’s extensive full-frontal nude scene in Daniel Petrie and Sidney Sheldon’s 1974 Buster and Billie is on display here, as are vintage clips of Sammy Davis Jr., adventurer Sir Wilfred Thesiger, former Vogue editor Diana Vreeland, and Robert Mitchum singing in a recording studio with Dr. John. The film is about model Peter Johnson and Weber as much as it is about the cult of celebrity; Weber gets to chime in on Elizabeth Taylor, Montgomery Clift, Clark Gable, Frank Sinatra, Arthur Miller, and dozens of other famous names and faces. Though an awful lot of fun, the film is disjointed, lacking a central focus, and the onscreen titles, end credits, and promotional postcards are chock-full of typos — perhaps emulating a Chinese takeout menu, hence the film’s title? Chop Suey is screening November 20 at 7:00 as part of Film Forum’s “Bruce Weber” series and will be preceded by Weber’s twelve-minute 2008 short, The Boy Artist; the series continues through November 21 with a 35mm print of Let’s Get Lost, 1987’s Broken Noses, about former Olympian boxer Andy Minsker, 2004’s A Letter to True, a tribute to Weber’s dog, and a compilation of shorts, videos, commercials, and works in progress.

Fashion photographer Bruce Weber, who directed the seminal Chet Baker doc Let’s Get Lost a quarter century ago, made this fun hodgepodge of still photos, old color and black-and-white footage, and new interviews and voice-over narration back in 2001. You might not know much about Frances Faye, but after seeing her perform in vintage Ed Sullivan clips and listening to her manager/longtime partner discuss their life together, you’ll be searching YouTube to check out a lot more. The film also examines how Weber selects and treats his male models, who are often shot in homoerotic poses for major designers (and later go on to get married and have children). As a special treat, Jan-Michael Vincent’s extensive full-frontal nude scene in Daniel Petrie and Sidney Sheldon’s 1974 Buster and Billie is on display here, as are vintage clips of Sammy Davis Jr., adventurer Sir Wilfred Thesiger, former Vogue editor Diana Vreeland, and Robert Mitchum singing in a recording studio with Dr. John. The film is about model Peter Johnson and Weber as much as it is about the cult of celebrity; Weber gets to chime in on Elizabeth Taylor, Montgomery Clift, Clark Gable, Frank Sinatra, Arthur Miller, and dozens of other famous names and faces. Though an awful lot of fun, the film is disjointed, lacking a central focus, and the onscreen titles, end credits, and promotional postcards are chock-full of typos — perhaps emulating a Chinese takeout menu, hence the film’s title? Chop Suey is screening November 20 at 7:00 as part of Film Forum’s “Bruce Weber” series and will be preceded by Weber’s twelve-minute 2008 short, The Boy Artist; the series continues through November 21 with a 35mm print of Let’s Get Lost, 1987’s Broken Noses, about former Olympian boxer Andy Minsker, 2004’s A Letter to True, a tribute to Weber’s dog, and a compilation of shorts, videos, commercials, and works in progress.