Connie Chatterley (Marina Hands) and gamekeeper Parkin (Jean-Louis Coulloc’h) explore sexual freedom in LADY CHATTERLEY

CINÉSALON: LADY CHATTERLEY (Pascale Ferran, 2006)

French Institute Alliance Française, Florence Gould Hall

55 East 59th St. between Madison & Park Aves.

Tuesday, November 11, $13, 4:00 & 7:30

Series continues Tuesdays through December 16

212-355-6100

www.fiaf.org

D. H. Lawrence’s oft-banned and censored Lady Chatterley’s Lover has been turned into several films, including highly erotic versions starring Sylvia Kristel, Patricia Javier, and Harlee McBride. But for his 2006 film, Lady Chatterley, French director Pascale Ferran turned to the second version of Lawrence’s tale of love, sex, and infidelity, adapting 1927’s John Thomas and Lady Jane into the César-winning Lady Chatterley. Marina Hands won a César as Best Actress for her sensitive portrayal of Constance Chatterley, wife of Sir Clifford Chatterley (Hippolyte Girardot), a bitter, wealthy aristocratic mine owner who was paralyzed from the waist down in World War I. Sent to give a message to the Chatterleys’ gamekeeper, Parkin (Jean-Louis Coulloc’h), Connie sees him with his shirt off, washing himself outside, and something instantly stirs inside her. She begins making frequent visits to his cabin in the forest, and soon they are having an affair. When Connie prepares to go on a trip with her sister, Hilda (Hélène Fillières), she hires Mrs. Bolton (Hélène Alexandridis) as Sir Clifford’s nurse, but Clifford and Mrs. Bolton grow suspicious of Connie’s long disappearances, forcing Connie to decide what path to take.

D. H. Lawrence’s oft-banned and censored Lady Chatterley’s Lover has been turned into several films, including highly erotic versions starring Sylvia Kristel, Patricia Javier, and Harlee McBride. But for his 2006 film, Lady Chatterley, French director Pascale Ferran turned to the second version of Lawrence’s tale of love, sex, and infidelity, adapting 1927’s John Thomas and Lady Jane into the César-winning Lady Chatterley. Marina Hands won a César as Best Actress for her sensitive portrayal of Constance Chatterley, wife of Sir Clifford Chatterley (Hippolyte Girardot), a bitter, wealthy aristocratic mine owner who was paralyzed from the waist down in World War I. Sent to give a message to the Chatterleys’ gamekeeper, Parkin (Jean-Louis Coulloc’h), Connie sees him with his shirt off, washing himself outside, and something instantly stirs inside her. She begins making frequent visits to his cabin in the forest, and soon they are having an affair. When Connie prepares to go on a trip with her sister, Hilda (Hélène Fillières), she hires Mrs. Bolton (Hélène Alexandridis) as Sir Clifford’s nurse, but Clifford and Mrs. Bolton grow suspicious of Connie’s long disappearances, forcing Connie to decide what path to take.

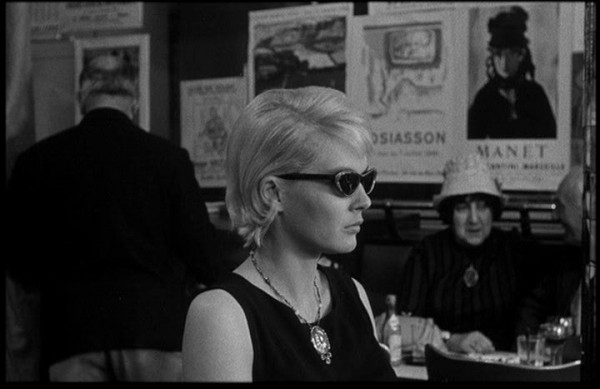

Marina Hands won a César as Best Actress for her moving portrayal of the title character in Pascale Ferran’s LADY CHATTERLEY

Lady Chatterley is no mere sex romp or erotic tale; Ferran (L’Âge des possibles, Bird People), who cowrote the César-winning script with Roger Bohbot and Pierre Trividic, treats the subject with an austere honesty. The sex scenes are not lurid but instead wholly believable as Connie and Parkin explore each other’s bodies and souls, their class differences creating a wall between them. The award-laden film also won Césars for Julien Hirsch’s lush yet old-fashioned cinematography and Marie-Claude Altot’s beautiful costume design, the precise details of which are particularly on display when Connie carefully undresses. The film is at times agonizingly slow-paced and too long at nearly three hours, but its overt Frenchness offers a fascinating take on a familiar story. Lady Chatterley is being shown November 11 at 4:00 and 7:30 as part of the French Institute Alliance Française CinéSalon series “The Art of Sex and Seduction,” with the later screening introduced by film critic Nicholas Elliott and followed by a wine reception; the series continues Tuesdays through December 16 with François Ozon’s Swimming Pool introduced by Ry Russo-Young, Alain Guiraudie’s Stranger by the Lake introduced by Alan Brown, Catherine Breillat’s The Last Mistress introduced by Melissa Anderson, and François Truffaut’s The Man Who Loved Women introduced by Laura Kipnis. There will also be talks, panel discussions, Jean-Daniel Lorieux’s “Seducing the Lens” photography exhibition, and other programs as part of “The Art of Sex & Seduction.”

French filmmaker Mia Hansen-Løve’s third film is an infuriating yet captivating tale that runs hot and cold. Goodbye First Love begins in Paris in 1999, as fifteen-year-old Camille (Lola Créton) frolics naked with Sullivan (Sebastian Urzendowsky), her slightly older boyfriend. While she professes her deep, undying lover for him, he refuses to declare his total dedication to her, instead preparing to leave her and France for a long sojourn through South America. When Camille goes home and starts sobbing, her mother (Valérie Bonneton), who is not a big fan of Sullivan’s, asks why. “I cry because I’m melancholic,” Camille answers, as only a fifteen-year-old character in a French film would. As the years pass, Camille grows into a fine young woman, studying architecture and dating a much older man (Magne-Håvard Brekke), but she can’t forget Sullivan, and when he eventually reenters her life, she has some hard choices to make. Créton (Bluebeard) evokes a young Isabelle Huppert as Camille, while Urzendowsky (The Way Back) is somewhat distant as the distant Sullivan. There is never any real passion between them; Hansen-Løve (All Is Forgiven,

French filmmaker Mia Hansen-Løve’s third film is an infuriating yet captivating tale that runs hot and cold. Goodbye First Love begins in Paris in 1999, as fifteen-year-old Camille (Lola Créton) frolics naked with Sullivan (Sebastian Urzendowsky), her slightly older boyfriend. While she professes her deep, undying lover for him, he refuses to declare his total dedication to her, instead preparing to leave her and France for a long sojourn through South America. When Camille goes home and starts sobbing, her mother (Valérie Bonneton), who is not a big fan of Sullivan’s, asks why. “I cry because I’m melancholic,” Camille answers, as only a fifteen-year-old character in a French film would. As the years pass, Camille grows into a fine young woman, studying architecture and dating a much older man (Magne-Håvard Brekke), but she can’t forget Sullivan, and when he eventually reenters her life, she has some hard choices to make. Créton (Bluebeard) evokes a young Isabelle Huppert as Camille, while Urzendowsky (The Way Back) is somewhat distant as the distant Sullivan. There is never any real passion between them; Hansen-Løve (All Is Forgiven,

When French U.N. delegate Fèvre-Berthier goes missing in director Jean-Pierre Melville’s 1959 noir, Two Men in Manhattan, reporter Moreau (Melville) of the French Press Agency and freelance photographer Pierre Delmas (Pierre Grasset) go out on the town, trying to find out what happened. While Moreau is seeking the truth, Delmas is after a sensationalist photograph he can sell to the highest bidder. They meet up with several women who knew the married diplomat — some much better than others — including his secretary, Françoise Bonnot (Colette Fleury), actress Judith Nelson (Ginger Hall), stripper Bessie Reid (Michèle Bailly), and jazz singer Virginia Graham (Glenda Leigh). As the men make their way through Rockefeller Plaza, Times Square, Greenwich Village, Broadway, the subway, and the United Nations, Marial Solal’s and Christian Chevallier’s jazzy score dominates the outdoor scenes, soaking the viewer in the New York at night atmosphere. And all the while, the reporter and photographer are trailed by someone in a mysterious car. As they get closer to their destination, they are faced with some serious ethical choices, not just about journalism, but about life itself. Nearly fifty-five years after its release, Two Men in Manhattan feels as stiff and dated as Melville’s (Bob le Flambeur, Le Doulos, Le Samouraï) lead performance, his only starring role and his sole appearance in one of his own films. It’s difficult to tell if Two Men in Manhattan is a serious procedural, an homage to classic noirs, a tribute to New York City, or a sly genre parody — perhaps it’s all of them, but far too many of the twists and turns are hard to swallow, especially when it comes to Delmas’s selfish decisions and Moreau’s often absurd brainstorms that seem to exist just to quicken the plot despite their incredulity. Still, it’s beautifully shot in shadowy darkness by Nicholas Hayer, and it was proclaimed by Jean-Luc Godard to be the second best film of the year. A digitally remastered version of Two Men in Manhattan is screening March 4 at 4:00 & 7:30 as part of the FIAF CinéSalon series “Remastered & Restored: Treasures of French Cinema”; the later screening will be presented by Phillip Lopate, and both shows will be followed by a wine reception. The three-month festival continues March 11 with Claire Denis’s Chocolat, introduced by African Film Festival founder Mahen Bonetti, before concluding March 18 with Henri-Georges Clouzot’s The Truth.

When French U.N. delegate Fèvre-Berthier goes missing in director Jean-Pierre Melville’s 1959 noir, Two Men in Manhattan, reporter Moreau (Melville) of the French Press Agency and freelance photographer Pierre Delmas (Pierre Grasset) go out on the town, trying to find out what happened. While Moreau is seeking the truth, Delmas is after a sensationalist photograph he can sell to the highest bidder. They meet up with several women who knew the married diplomat — some much better than others — including his secretary, Françoise Bonnot (Colette Fleury), actress Judith Nelson (Ginger Hall), stripper Bessie Reid (Michèle Bailly), and jazz singer Virginia Graham (Glenda Leigh). As the men make their way through Rockefeller Plaza, Times Square, Greenwich Village, Broadway, the subway, and the United Nations, Marial Solal’s and Christian Chevallier’s jazzy score dominates the outdoor scenes, soaking the viewer in the New York at night atmosphere. And all the while, the reporter and photographer are trailed by someone in a mysterious car. As they get closer to their destination, they are faced with some serious ethical choices, not just about journalism, but about life itself. Nearly fifty-five years after its release, Two Men in Manhattan feels as stiff and dated as Melville’s (Bob le Flambeur, Le Doulos, Le Samouraï) lead performance, his only starring role and his sole appearance in one of his own films. It’s difficult to tell if Two Men in Manhattan is a serious procedural, an homage to classic noirs, a tribute to New York City, or a sly genre parody — perhaps it’s all of them, but far too many of the twists and turns are hard to swallow, especially when it comes to Delmas’s selfish decisions and Moreau’s often absurd brainstorms that seem to exist just to quicken the plot despite their incredulity. Still, it’s beautifully shot in shadowy darkness by Nicholas Hayer, and it was proclaimed by Jean-Luc Godard to be the second best film of the year. A digitally remastered version of Two Men in Manhattan is screening March 4 at 4:00 & 7:30 as part of the FIAF CinéSalon series “Remastered & Restored: Treasures of French Cinema”; the later screening will be presented by Phillip Lopate, and both shows will be followed by a wine reception. The three-month festival continues March 11 with Claire Denis’s Chocolat, introduced by African Film Festival founder Mahen Bonetti, before concluding March 18 with Henri-Georges Clouzot’s The Truth.

After his dog runs away, a homeless tramp jumps into the Seine, only to be rescued by a bookseller who brings him home to stay with his family in Jean Renoir’s 1932 masterpiece, Boudu Saved from Drowning. Adapted by Renoir from René Fauchois’s play — the brief opening scene takes place onstage, announcing that what is to follow is essentially a fable — the depression-era social satire centers on the relationship between the wacky, unpredictable bum, Priapus Boudu (Michel Simon, who also played the lead in the play), and Edouard Lestingois (Charles Granval), a bourgeois bookstore owner cheating on his wife, Emma (Marcelle Hainia), with one of their maids, Anne-Marie (Sévérine Lerczinska). Lestingois first spots Boudu while looking through his telescope at the masses on the Pont des Arts, like a filmmaker shooting a documentary; “I’ve never seen such a perfect tramp!” he declares. (Indeed, Renoir regularly comments on the art of filmmaking in Boudu, especially with his use of music, nearly all of which is eventually revealed to be coming from natural sources.) Lestingois helps save the suicidal Boudu, nursing him quickly back to health and letting him stay at the house, much to the chagrin of his wife. Rather than being thankful, Boudu is a whirling dervish of ill manners, breaking dishes, using fancy lingerie to shine his shoes, and daring to eat sardines with his hands. Despite Boudu’s rudeness, Edouard, Emma, and Ann-Marie are all drawn to him in different ways, particularly Edouard, who dresses Boudu in his clothes as if he were a kind of doppelgänger, an alternate version with a completely different set of expectations and responsibilities. But there’s no controlling the bushy-haired Boudu, who reacts to all stimuli like a child who does whatever he wants, not caring about the consequences. One of the keys to the film is that very barrier, the question as to whether Boudu is a conniving tramp who knows exactly what he’s doing or just a pitiable poor soul with no self-control. Boudu — and, therefore, Simon, who gives a towering, spectacular performance, one of the greatest of early cinema — is part Charlie Chaplin, part Buster Keaton, part Little Rascal, and the influence of the character extends to Denis Lavant’s underground creature in Léos Carax’s Merde short in the Tokyo! omnibus and Eddie Murphy’s Billy Ray Valentine in John Landis’s Trading Places. (The film has also been remade twice; Paul Mazursky’s Down and Out in Beverly Hills stars Nick Nolte as the tramp, while Gérard Depardieu plays the role in Gérard Jugnot’s 2005 Boudu.)

After his dog runs away, a homeless tramp jumps into the Seine, only to be rescued by a bookseller who brings him home to stay with his family in Jean Renoir’s 1932 masterpiece, Boudu Saved from Drowning. Adapted by Renoir from René Fauchois’s play — the brief opening scene takes place onstage, announcing that what is to follow is essentially a fable — the depression-era social satire centers on the relationship between the wacky, unpredictable bum, Priapus Boudu (Michel Simon, who also played the lead in the play), and Edouard Lestingois (Charles Granval), a bourgeois bookstore owner cheating on his wife, Emma (Marcelle Hainia), with one of their maids, Anne-Marie (Sévérine Lerczinska). Lestingois first spots Boudu while looking through his telescope at the masses on the Pont des Arts, like a filmmaker shooting a documentary; “I’ve never seen such a perfect tramp!” he declares. (Indeed, Renoir regularly comments on the art of filmmaking in Boudu, especially with his use of music, nearly all of which is eventually revealed to be coming from natural sources.) Lestingois helps save the suicidal Boudu, nursing him quickly back to health and letting him stay at the house, much to the chagrin of his wife. Rather than being thankful, Boudu is a whirling dervish of ill manners, breaking dishes, using fancy lingerie to shine his shoes, and daring to eat sardines with his hands. Despite Boudu’s rudeness, Edouard, Emma, and Ann-Marie are all drawn to him in different ways, particularly Edouard, who dresses Boudu in his clothes as if he were a kind of doppelgänger, an alternate version with a completely different set of expectations and responsibilities. But there’s no controlling the bushy-haired Boudu, who reacts to all stimuli like a child who does whatever he wants, not caring about the consequences. One of the keys to the film is that very barrier, the question as to whether Boudu is a conniving tramp who knows exactly what he’s doing or just a pitiable poor soul with no self-control. Boudu — and, therefore, Simon, who gives a towering, spectacular performance, one of the greatest of early cinema — is part Charlie Chaplin, part Buster Keaton, part Little Rascal, and the influence of the character extends to Denis Lavant’s underground creature in Léos Carax’s Merde short in the Tokyo! omnibus and Eddie Murphy’s Billy Ray Valentine in John Landis’s Trading Places. (The film has also been remade twice; Paul Mazursky’s Down and Out in Beverly Hills stars Nick Nolte as the tramp, while Gérard Depardieu plays the role in Gérard Jugnot’s 2005 Boudu.)