Richard Maxwell’s Field of Mars explores the history of human existence from an Applebee’s in Chapel Hill, North Carolina (photo by Whitney Browne)

NEW YORK CITY PLAYERS: FIELD OF MARS

NYU Skirball

566 LaGuardia Pl.

January 19-22, 24-29, $60

publictheater.org

nyuskirball.org

“OMG.”

That three-letter digital exclamation is said throughout Richard Maxwell’s new play, Field of Mars, stated plainly by several characters as if it is just another article or preposition. As has been Maxwell’s style since he started his company, New York City Players, in 1999, all words are given similar treatment, delivered dryly, sans any deep emotion, all of equal weight and meaning. omg.

Named after an ancient term for a large public space or military parade ground, Field of Mars is about the beginning and the end of everything on Earth, with God himself portrayed by Phil Moore, who, with equal weight and meaning, also plays a manager at an Applebee’s in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, which serves as a kind of way station for humanity.

The audience sits on four rows of rafters onstage, facing the actors, in the otherwise empty NYU Skirball Center, which commissioned the piece for the Public’s Under the Radar Festival. The nonlinear story takes place on lighting designer Sascha van Riel’s relaxing set, a relatively featureless restaurant booth on one side, a bar/hostess station on the other, where Gillian Walsh is an alternate version of St. Peter at the gates of heaven, more concerned with her cover band and her BF than the future of the planet. The set is reminiscent of the one van Riel built and gets torn down in Maxwell’s The Evening, identified in that 2015 work as “a garbagey void” in “a lonely corner of the universe.”

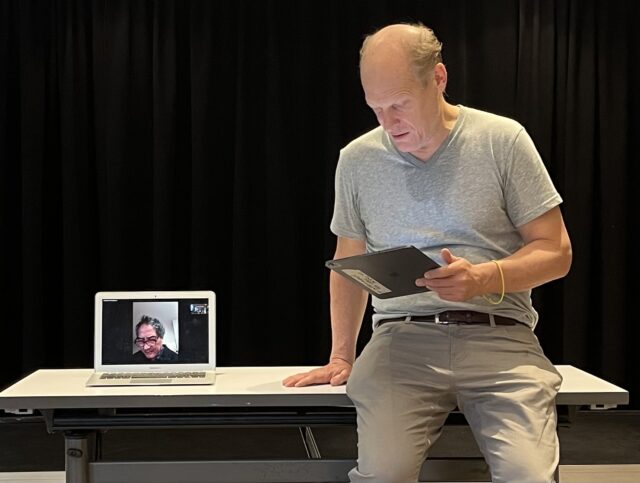

Brian Mendes and Jim Fletcher rehearse for NYCP’s Field of Mars (photo courtesy New York City Players)

The show opens with Adam (Brian Mendes) and Eve (Walsh) in the Garden of Eden, disguised as a popular American chain eatery, and moves through various bizarre, seemingly unconnected scenarios involving music, invisible food, both evolution and creationism, and one hell of an orgy.

In the lengthiest segment, an early version of which I saw at the Clemente and is now more fully formed, two older musicians (Jim Fletcher and Mendes, the latter in his trademark Jerry Garcia T) are pitching their new song to a pair of younger producers (Nicholas Elliott and James Moore), one of whom is, well, an asshole who claims that punk rock never existed. The men’s long, Don DeLillo–like list of cool bands could have used some shortening — the play is too long at two and a half hours, with intermission — but Maxwell (The Vessel, Isolde, Paradiso) is not in a hurry here.

Characters in Kaye Voyce’s everyday costumes walk and squiggle slowly, the narrator (Tory Vazquez) has an extensive phone conversation about pigments with what sounds like a chatbot, early humans (Elliott, James Moore, Eleanor Hutchins, and Paige Martin) evolve, and three of the musicians, after discussing what their songs are really about, lamely “jam” on electric guitars, which are not plugged into amps, as life goes on around them. Meanwhile, the Applebee’s employees (Walsh, Moore, Martin, Lakpa Bhutia) wear masks around their chins as if understanding there’s a health crisis but not worrying about it.

So, what is Field of Mars really about? As one character notes, “Sometimes the confusion is part of it.” Perhaps we’re sitting onstage because we’re all part of this confusion, part of the problem as we potentially face the end times, masks around our chins.

There’s no program, just a glossy one-sheet with only the most basic of information, along with a free souvenir paper poster that features a drawing of a stick figure in a doorway on one side and advises on the other, “I promise I will not look to the natural world to make up for my lack of spirituality ever again.”

OMG. It all makes perfect sense to me.